Tags

African cuisine, African restaurants in Paris, Antillean cuisine, Au Village, Baifall Dream Theranga Salon de Thé, Chez Aïda, French cuisine, French food, Kiratiana's Travel Guide to Black Paris: Get Lost and Get Found, Le Nioumré, Le Petrossian 144, Moussa l'Africain, Senegalese restaurants in Paris, Senegalese thieb, Thieb le Nouveau Paris-Dakar, Thieboudienne

Share it

By Kiratiana Freelon

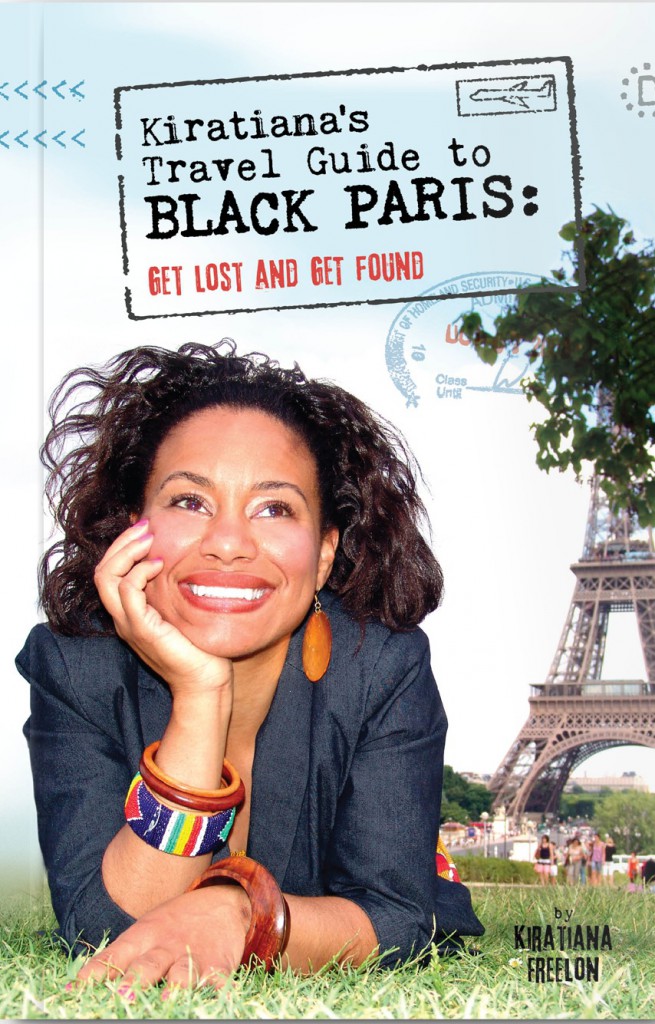

“Eating: Afro and French (in Paris)” takes us into the city’s eclectic ethnic eateries, where Antillean cuisine and Sénégalese theib offer colorful and creative respite from more typical Parisian meals from the book Kiratiana’s Travel Guide to BLACK PARIS: Get lost and get found by Kiratiana Freelon (used by permission).

French cuisine: on a quest for black Paris? France is famed for some of the finest cuisine in the world, and enjoying a three-star meal with every luxurious trimming or even a fresh baguette with some unpronounceable cheese is sure to be a highlight of your visit. Gastronomy is the pinnacle of French culture—which is saying something in this land of monumental art and world-changing ideas—and is as much a marriage of ritual and history as of form and flavor.

Although you must sample the highlights of traditional French cuisine, visitors on a quest for black Paris will also be drawn into the city’s eclectic ethnic eateries, where Antillean cuisine and Senegalese theib offer colorful and creative respite from more typical Parisian meals.

Wining and Dining Like the Parisians Do

There are a few things that you just don’t do in America, but in France they seem Trés Chic.

• Seating yourself in a restaurant. Normally, if you have to seat yourself in the States, you’re about to drop US$15, tops. But in Paris, you’ll have to seat yourself even if you’re spending €50. Don’t just stand there, have a seat.

• Using your bare hands to tear a hunk off the communal piece of bread. For that matter, the French use their bare hands to pluck up a pastry, carry a baguette down the street, or even pick out your candy or bread at the store (as I have seen many times). Just think of it as being more natural …

• Sopping up your plate. The French have no qualms about using that last piece of baguette to sop up some bouillabaisse sauce. Every French person I’ve ever eaten with does it, so don’t be ashamed to do the same!

• Carrying a wine bottle and glass, around the city. There is absolutely nothing unusual about enjoying a glass of wine in front of the Sacré Coeur. That’s Paris. But, if you carry around a 16 oz. can of Guinness, then that’s just not right …

What to Expect When Dining Out

In France, a meal is so much more than a meal—it is an experience, leisurely and refined, whether an impromptu picnic at one of Paris’ pleasant parks or a multiple-course meal at one of the city’s three-star restaurants. Abandon your American fast-food expectations. You are expected to linger over your meal among friends and strangers, savoring every flavor and turn of conversation as though life as a precious gift to be appreciated, rather than a race to be won.

When to Eat

Breakfast can be taken at your corner café or boulangerie (bakery) any time, but lunch hours are fairly strict, from noon to 2:30 pm or so. Many restaurants close between 2:30 pm and 7:30 pm. Brasseries, on the other hand, serve food all day. Dinner is served late by American standards; if you want to be the only person in the restaurant, arrive before 8 pm. Otherwise, any time between 8:30 pm and 11:30 pm would be perfect.

Le Menu or à la Carte?

Most restaurants offer two choices: wide range of options served à la carte (usually the more expensive option), or le menu, which is not a list of dishes, but rather a well-priced special that usually includes the entrée (appetizer), plat (main course), dessert (dessert), and perhaps a drink. There may also be a fromage (cheese) course. Traditionally, French people eat a cheese platter between the plat and dessert, or in place of dessert. A good cheese platter will include a soft cheese, hard cheese and some chèvre (goat cheese).

Service and Tipping

The quality of service in Paris might not meet your American expectations unless you are eating in a three-star restaurant. French service is notoriously slow, and even slower in Antillean and African restaurants, where you should plan to linger at least 3 hours over your meal. Be ready to fight for the wait staff’s attention, as each typically serves 10 or more tables. The gratuity (15–20%) is almost always included in the meal price, and servers typically receive a salary. French people almost never tip, and you shouldn’t feel pressured to do so unless the service is amazing.

Serving Size

French servings are typically smaller than American portions. This does not mean you won’t feel satisfied, however. Most French people typically eat all three courses (entrée, plat and dessert) at dinnertime, and two at lunch. Each of these courses might be small, but after all three, as well as some bread and a glass of wine (or two), you will feel satisfied but not overly full.

Prices

In general, having an unrushed dinner in a decent restaurant will cost at least €25–40. Since restaurants generally do not turn tables, you can stay all night without anyone offering the bill—ask for it when you are ready. Quality tends to correlate strongly with price, but all the restaurants included in this guide offer good value for your euro. Budget travelers can eat well at bakeries, cafés, and grocery stores for just a few euro.

Thieboudienne: A Taste of Senegal in Paris

While most people cherish Paris for its crêpes, croque-monsieurs, and classic French cuisine, I come for the thieboudienne (cheb-oo-jen), a simple-looking yet complex Senegalese dish of parsley, seasoned fish, rice, tomatoes, and vegetables.

My first taste of grand thieb, in Senegal, erased all my misconceptions of African food: mushy vegetables that didn’t taste good. Subsequent travels across West Africa revealed that Senegalese cuisine, and thieb in particular, is at the apex of African gastronomy, just as French cuisine is considered Europe’s finest. In Paris, some 70% of all African restaurants specialize in Senegalese food.

According to oral tradition, thieb is the creation of Penda Mbaye, a woman from Saint Louis, Senegal. A cook at the colonial governor’s residence during the 19th century, she first created the dish of fish and vegetables using barley. During a barley shortage, however, she substituted rice, which at the time was still foreign a luxury good from Asia. Eventually, thieb became Senegal’s national dish.

In Senegal I observed a Senegalese woman spend 4 full hours preparing the dish. First, she stuffed a mixture of salt, pepper, onions, and parsley into a thiof—a tough fish that withstands a nice deep fry without falling apart. After retrieving the fried fish from the peanut oil, she dumped one can of tomato sauce and a liter of water into the oil. She then added a pungent dried fish, giving the thieb even more flavor, followed by a colorful assortment of squash, carrots, manioc, cauliflower, eggplant, sweet potatoes, onions, and one red scotch bonnet pepper. After simmering for 20 minutes, she removed the cooked vegetables from the sauce, and dumped in the twice-broken rice, which Senegalese prefer to long-grain rice.

She then dumped the rice in a big bowl and placed the vegetables on top. After several liberal squirts of fresh lime juice, the Senegalese woman, her 5 year-old son, and I dug into the thieb with our hands. Afterward, we drank some homemade bissap, a sweet drink made from hibiscus leaves.

There’s no need to try this recipe at home, not when you can leave it to Paris’ best African and Senegalese restaurants, usually for dinner. La Nioumré and Chez Aïda are the only places I would eat a thieb for lunch, as the dish is simply too complicated for most cooks to make correctly during the day.

Here are a few of my favorite restaurants, but adventurous eaters intent on discovering their own favorite restaurant should keep in mind that, as a rule of thumb, the closer to an African community or market, the better the thieb. Beware eateries offering both African and Antillean food—good restaurants do one or the other, and the best specialize in Senegalese cuisine. Servings are large, so there’s no need to order an entrée. And no matter where you end up enjoying your meal, always finish up with a glass of mint tea, the way Senegalese patrons do.

Best Birthday Party & Most Centrally Located

Thieb le Nouveau Paris-Dakar

11 rue Montyon, 9th

Tel: 01 42 46 12 30

Métro: Grands Boulevards

Hours: Mon–Sat 11:30 am–5 pm & 7 pm–1 am,

closed Fri lunch

Thieb: €16

This restaurant has been serving thieb to Paris’ Senegalese elite for 20 years. Owner/waiter/barman Mamadou works the 90-seat restaurant with dexterity, while Senegalese and Ivorian music videos make for a festive if kitschy atmosphere.

Book this restaurant for your large parties and intellectual dinner discussions.

Most Bohemian Thieb

Baifall Dream Theranga Salon de Thé

20 rue des Dames, 17th

Métro: Place de Clichy

Hours: Thieb starts at 8 pm Friday

Thieb: €12

Every Friday, Baifall Dream creator/artist/clothing designer Mike Sylla invites the Parisian art community to his tea salon for a reasonably priced, family-style thieb.

Most Historical Thieb

Chez Aïda

48 rue Polonceau, 18th

Tel: 01 42 58 26 20

Métro: Château Rouge

Hours: Mon–Sat noon–midnight

Theib: €10

Aïda, the original owner, has retired to Senegal, but her restaurant still churns out one of the best-value (many Senegalese simply say “best”) thiebs in Paris. Chez Aïda is the city’s oldest African restaurant, and was featured prominently in the 1985 black French comedy classic, Black Mic Mac. Don’t expect trendy tropical décor; this simple spot’s claims to fame are the food and its legacy.

Most Elegant Thieb

Moussa l’Africain

25-27 ave Corentin Cariou, 19th

Tel: 01 40 36 13 00

Métro: Porte de la Villette

Hours: Mon–Sun noon–2:30 pm & 7:30 pm–11:30 pm

Thieb: €22.50

Moussa l’Africain raised the standards—and prices—of Paris’ African restaurant scene with its 2006 opening. The classy ethnic décor, uniformed waiters, two-room seating (250 seats), and live music on weekends make this one high-class package. Cameroonian executive chef Alexandre Bella Ola also authored the award-winning African cookbook, Cuisines actuelle de l’Afrique Noire, which includes the recipe for his classic thieb.

Best Pre-Party Thieb

Au Village

86 ave Parmentier, 11th

Tel: 08 26 10 11 25

Métro: Parmentier

Hours: Mon–Sun 8 pm–midnight

Thieb: €13

With its inexpensive thieb, enthusiastic following (including the brother of Chez Aïda’s manager) and outstanding location, Au Village serves as the perfect jumping-off point for a night out in Paris. Reservations are not accepted, but on a nice night you can enjoy your thieb outdoors and then dance the night away in an Oberkampf club around the corner.

Best-Value Thieb

Le Nioumré

7 rue des Poissonniers, 18th

Tel: 01 42 51 24 94

Métro: Château Rouge/Barbes-Rouchechouart

Hours: Tues–Sun noon–11 pm

Thieb: €9.50

The line at Le Nioumré on a Saturday afternoon is out the door, but the food is well worth the wait. Only 30 people fit into two tiny rooms. Try to get the window seat on the right side, a window into life in Château Rouge. During my 3-hour lunch, I saw a wedding party, two Islamic prayer sessions at the mosque across the street, and countless families just enjoying the day.

Kiratiana Freelon is a Harvard graduate who has traveled to more than 25 countries and appeared on the Travel Channel as an expert on Paris. The Chicago native’s passion for travel, sports, and culture led her to work on Chicago’s bid for the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

She is now launching a series of “Black” destination travel guides and hopes to inspire people to “lose” themselves in travel.

She is now launching a series of “Black” destination travel guides and hopes to inspire people to “lose” themselves in travel.

Kiratiana Freelon author of Kiratiana’s Travel Guide to Black Paris: Get Lost and Get Found.

Visit: (Website)(Facebook)(Twitter)(Purchase)

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post, African Queen of Parisian Cuisine, from Kiratiana’s Travel Guide to BLACK PARIS: Get Lost and Get Found, by Kiratiana Freelon who writes about the “African Queen of Parisian Cuisine.” Featuring suggestions such as Le Petrossian 144, in Paris, where the head chef is Rougui Dai, a Frenchwoman of Sénégalese decent. There are more than 2,000 French restaurants in Paris. Of the 400 that the Michelin Guide found worth listing, only 77 receive on of their coveted stars. And of those starred restaurants, only one has a black, female head chef: Le Petrossian 144.

French Women Chefs: les mères lyonnaise, by French writer Laurence Haxaire who tells the stories of former house cooks of affluent families in Lyon who set up their own businesses after the French revolution in the 19th century. And later, when their reputation reached beyond the edge of Lyon, the most famous of them even welcomed such well-known people as General de Gaulle as a VIP at their table.

French Cuisine: Cooking schools in Paris founded by women, by Barbara Redmond who writes about extraordinary women who cook: from Anne Willan, Marthe Distel, and Elisabeth Brassart, to “Les trios gourmands,” Julia Child, Simone Beck, and Louisette Bertholle. Including a directory of cooking schools in Paris.

The Veuve Barbe-Nicole Clicquot and other Widowed women entrepreneurs, by Canadian writer Philippa Campsie who tells about the fast track to business independence or indeed, any kind of independence. Two hundred years ago, for many women, this independence was gained through widowhood. The story of Barbe-Nicole Clicquot, better known as Veuve (Widow) Clicquot, was a story that also happened to Louise Pommery, Lily Bollinger, and Mathilde Laurent-Perrier, and a few others.

Le Cordon Bleu Paris: Another “Sabrina” story, by Karen Cope who writes about her experiences at the famous Cordon Bleu cooking school, where she was a student. She shares with readers the recipes and methods of the famous school as she experienced them through classes: two Basic Pastry classes, Basic Cuisine and Intermediate Pastry. Including a list of cooking schools in Paris.

Text copyright ©2012 Kiratiana Freelon. All rights reserved.

Illustration copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com

Special guest writer Kiratiana Freelon author of Kiratiana’s Travel Guide to Black Paris: Get Lost and Get Found. Used by permission. Eunique Press (2010).

Kiratiana Freelon is a Harvard graduate who has traveled to more than 25 countries and appeared on the Travel Channel as an expert on Paris. The Chicago native’s passion for travel, sports, and culture led her to work on Chicago’s bid for the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

She is now launching a series of “Black” destination travel guides and hopes to inspire people to “lose” themselves in travel. Website, Blogsite, Facebook, Twitter, Purchase.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post, The African Queen of Parisian Cuisine, excerpts from Kiratiana’s Travel Guide to BLACK PARIS: Get Lost and Get Found, by Kiratiana Freelon about the “African Queen of Parisian Cuisine,” featuring suggestions such as Le Petrossian 144, Paris, where the head chef is Rougui Dai, a Frenchwoman of Senegalese decent. There are more than 2,000 French restaurants in Paris. Of the 400 that the Michelin Guide found worth listing, only 77 receive one of their coveted stars. And of those starred restaurants, only one has a black, female head chef: Le Petrossian 144.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post, Chocolate Mousse — debonair, dark and irresistibly rich! by Barbara Redmond who looks into this crème de la crème of mousses and uncovers the source of the original dish. Mousse as the supreme seducer was first known as “Mayonnaise de Chocolat,” created in the 1900s by French post-impressionist artist, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Recipe included for Mousseline au Chocolat (Chocolate Mousse), by Julia Child from her book, The French Chef Cookbook.

Indulge at Le Meurice Hôtel, Paris, by Parisian Eva Izsak-Niimura who shares how to achieve a bit of luxury at Le Meurice Hôtel, Paris for afternoon tea or evening cocktails, when “constraint” is a word more in vogue than “indulgence.”

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post, French Onion Soup — a Paris meal to remember, by Michelle Hum who recalls the aroma of sweet caramelized onions, dry wine, and rich broth rising from the steam from her bowl. With the first taste—serendipity. Recipe included for Julia Child’s Soupe à l’oignon (French onion soup) from her cookbook, The Way to Cook.

Pain Perdu: Childhood love of French custard and bread, by Barbara Redmond who shares her discovery of pain perdu (French toast), from the boulangerie pâtisserie Calixte in Île St. Louis, Paris. Barbara experiences French toast as a favorite treat eaten in the gardens of Notre Dame in an air of whimsy and childhood delight. Recipe included for “original French toast,” made by Christophe Raoux of L’École de Cuisine d’Alain Ducasse for Mark Schatzker, ABC News explore.

Text copyright ©2012 Kiratiana Freelon. All rights reserved.

Illustration copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com

2 comments

Kiratiana said:

March 6, 2012 at 5:19 pm

Hi Barbara! I want to thank you sook much for posting this information on your website for me!

Barbara Redmond, A Woman’s Paris™ said:

March 6, 2012 at 7:26 pm

Hi Kiratiana,

With pleasure! We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your life. A free spirit who inspires both admiration and confidence. I hope we may interview you for A Woman’s Paris to share with viewers what’s behind that inspiration of yours!

Mille merci et à bientôt!

Barbara Redmond