Tags

Eugène Ionesco, European intellectual life, France, French realists, French romantics, Hans Christian Anderson little mermaid, Let Petit Prince Antoine de Saint-Exupery, Napoleonic Wars, On a Little Prince Yara Zgheib Aristotle at Afternoon Tea, Paris, The Enlightenment

Share it

“On a Little Prince” by Yara Y. Zgheib. © 2015 Yara Y. Zgheib. Published with permission. All rights reserved.

Of all the infinite possible ways of categorizing the people of this world, I have always found those conventionally adapted to be unimaginative and odd. Surely gender, age, height, and weight are not more descriptive of a person than their favorite smell, the sound of their voice, the side of the bed they sleep on, the lumps of sugar in their tea? So I developed a method of my own: I categorize people by storm names.

There are those who believe that storms are named after heartbreak; each storm is a lover lost, abandoned, a lover who has left. They are those who look at sea foam and see Hans Christian Anderson’s little mermaid, who died for love and turned into soft white bubbles floating on the surface of the sea.

Let us call them romantics.

Then there are those who read in some scholarly publication that storms are given names to make them easier for sailors to distinguish; an alphabetical list is drawn up at random by weather scientists each year. There are also those for whom sea foam is but decaying algal blooms, dissolved organic matter that the agitation of the wind and waves churns up.

Let us call them realists.

Realists see the world for what it is. Romantics, for what they want it to be. The terms were used to define two opposing trends in European intellectual life in the aftermath of the Enlightenment. Cultural romanticism came first, after the Napoleonic Wars. It glorified mysticism and emotions, and saw individuals as heroes with a manifest destiny to change the world. But the failed populist revolutions of 1848 shattered those idealistic notions, and from the gritty pragmatism that remained emerged a realism that shifted the focus to more concrete subject matters. Realists saw hardship and social injustice, and their art and literature reflected it.

Not unlike children and grownups, perhaps?

Seventy-two years and three days ago, a fascinating treatise was published on these two categories of people. It sold more than 150 million copies and was translated into 260 languages and dialects. The title: Le Petit Prince (The Little Prince), by Antoine de Saint-Exupery.

The book tells the story of a little boy’s travels to seven asteroid planets, including Earth, and his encounters with their inhabitants. He met a king, a conceited man, a drunkard, a businessman, a lamplighter, a geographer… but also a talking fox, a wise serpent, and a rose unlike any other in the whole universe, if only for the fact that he loved her.

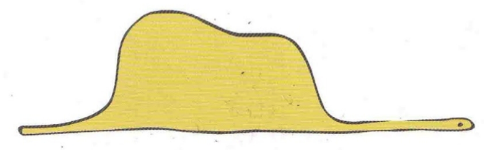

Grown-ups and children, he found, were easily distinguishable by what they saw in a particular illustration, creatively named “Drawing Number 1”:

Grown-ups and children, he found, were easily distinguishable by what they saw in a particular illustration, creatively named “Drawing Number 1”:

Children, of course, immediately saw an elephant inside a boa constrictor. Grown-ups saw a bowler hat, or worse—nothing at all, even with the help of explanatory “Drawing Number 2”:

Children, of course, immediately saw an elephant inside a boa constrictor. Grown-ups saw a bowler hat, or worse—nothing at all, even with the help of explanatory “Drawing Number 2”:

“All grownups were once children, but only few of them remember it.” —Antoine de Saint-Exupery

Romanticism is beautiful, and childhood is sweet, but sooner or later we grow up—a sad, inevitable byproduct of knowledge and disillusion. In time and with wear, we willingly put on the blinders that make us forsake whimsy for utility, possibility for security, boa constrictors for bowler hats. In a world that runs on hard facts, realism is the only guarantee of survival.

But there is a danger in leaving those blinders on too long: Eventually, we lose sight of the world beyond them. Our occupations confine us, our self-set limitations trap us. The world, as it is, makes us bitter, and we slump into passivity. We forget we could once see elephants in boa constrictors too.

Realism shrinks reality, “attenuates it, falsifies it; it does not take into account our basic truths and our fundamental obsessions: love, death, astonishment. It presents man in a reduced and estranged perspective. Truth is in our dreams, in the imagination.” —Eugène Ionesco

We may have our science, our figures and our facts, but we still need our romantics. We must nurture the artists and the daydreamers, the fortune cookie readers and the wildflower pickers, the well-wishers and the sunset lovers, the eternal children. As the little prince said, their ability to see beauty is utility enough.

Once upon a time, I was fortunate enough to have known and loved such a child: a real little prince who saw the world in color, and me for much more than I was. His clouds were shaped like castles, his bright turquoise tennis shoes were magic, and the last time I saw him, he was building a rainbow machine. His world may not have been real, but it is the one I prefer.

There are two categories of people in this world: those who see it for what it is, and those who, like you little prince, will always be seven years old. Happy birthday.

Acknowledgements: Lee Murphy, student of new media communications at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities and copy editor A Woman’s Paris.

Illustration “Castle on the Cloud” © 2014-2015 Yara Zgheib. All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations “Drawing Number 1” and “Drawing Number 2” © Antoine de Saint-Exupery from Le Petit Prince.

Born in Lebanon, Yara Y. Zgheib has traveled and lived in Glasgow, Washington D.C., and Paris, the city that forever has her heart. She is a Fulbright scholar with a Masters degree in security studies and an all but completed PhD in international affairs and diplomacy. More importantly, she is a writer, a political analyst, a daydreamer, and an avid tea drinker.

Born in Lebanon, Yara Y. Zgheib has traveled and lived in Glasgow, Washington D.C., and Paris, the city that forever has her heart. She is a Fulbright scholar with a Masters degree in security studies and an all but completed PhD in international affairs and diplomacy. More importantly, she is a writer, a political analyst, a daydreamer, and an avid tea drinker.

Yara is the author of “Biography of a Little Prince,” and has a second novel, “Letters I’ll Never Send,” scheduled for release in 2015. Her blog, “Aristotle at Afternoon Tea,” is a compilation of weekly essays on politics, art, culture, economics, literature, philosophy, and chocolate… her idea of a smart conversation over afternoon tea. For more information about Yara, visit: (Aristotle at Afternoon Tea)

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post On Aches and Madeleines by Yara Y. Zgheib. “La madeleine de Proust. A happy memory unconsciously elicited by a fleeting sensory experience—a scent, a taste, a few notes from an old tune—a vague, bittersweet memory, of the kind that makes our lower lips quiver and our hearts ache. That ache, Proust’s madeleine, is universal. Looking back is not just universal; it is endearingly human.

On Doing and Being by Yara Y. Zgheib. “La bohème.” It was French novelist Henri Murger who first romanticized the expression in his 1847 novel, ‘Scènes de la vie de bohème.’ For Murger it came to mean ‘a world of artists, social rebels, and radicals who rejected the comforts of the bourgeoisie, opting instead for poverty, and believing that any true experience demanded suffering. They were committed to a life of freedom, work, and pleasure, and eschewed the corruption and rotten values of conventional society.’ Trust the Parisians to elevate starving to death to an art form.

On Fifth Avenue, at Five in the Morning by Yara Y. Zgheib. In the legendary opening scene, a slender Holly Golightly in black Givenchy evening gown eats a Danish and peers into the windows of a closed jewelry store on a deserted Fifth Avenue in New York City. She has what she calls the “Mean Reds,” that errifying feeling you get when life has been unkind and the future is uncertain. “What we believe,” writes Yara “is not as important as why we believe.”

Travel Diaries: On A Moveable Feast (Paris) by Yara Y. Zgheib. Only in Paris can a cold and rainy April day be romantic. Yara takes us cobblestone streets and narrow steps; Acrocc bridges and through gilded archways: Into smelly cheese shops and out of crowded Thursday markets: Past the queue of ignorant tourists outside Ladurée and toward the infinitely better Pierre Hermé. “A weekend in Paris is not enough,” writes Yara. “Nor is a year, or a lifetime. One more café-croissant express, then she heads for the plane.

The Art Diaries: From Paris to Bretagne (part one) by Lilianne Milgrom. An artist and writer, Lilianne Milgrom is Paris-born, grew up in Australia, lived for extensive periods in Isreal, and currently resides in Washington D.C. A Winter’s Diary was written during her recent trip to Paris where she curated an exhibition at Saint-Germain des Prés, followed by an extended stay in Dinan as artist-in-residence under the auspices of Yvonne Jean-Haffen Museum. The Art Diaries, first published on AWomansParis.com, are excerpts from her journal A Winter’s Diary.

Doing the bridge “faire le pont” in Paris by Parisienne Bénédicte Mahé. Every year, the month of May is full of promises for people working in France: the promises of numerous public holidays. Between May 1st and May 8th we look for maybe three four-day weekends. Because what is a French person to do, except take Friday off when Thursday is a public holiday? In French we call that faire le pont, “do the bridge”. What do people do during these long weekends? Well…

A literary feast – Cafés and culture in Paris’ 9th arrondissement by Parisian Flore der Agopian. Paris has always been an inspiration for writers and painters, both from France and all over the world. Flore explores how cafés in nineteenth century Paris inspired literary figures Emile Zola, Alexandre Dumas, George Sand, Guy de Maupassant, Marcel Proust and French painters Edgar Degas, Eugène Delacroix, Camille Pissaro, and Edouard Manet. Including a list of current cafés in Paris’ 9th arrondissement.

To the South of France with Love. Sara Horsley invites us into her world to share six weeks in Arles, France, during a study abroad program. There, she learned about the French culture and their respect and admiration of artistic expression.

A Woman’s Paris: A global gateway to everything French, by Eric Best (reprinted with permission from A Northeast Francophile, published by the Journal). While Barbara Redmond is far from an aristocratic jetsetter, she once thought of herself as a Francophile. A Woman’s Paris readers can expect posts of French art and literature, first-person stories from Redmond and contributors about travelling and interviews with authors.

Text copyright ©2015 Yara Y. Zgheib. All rights reserved.

Illustration copyright ©2015 Yara Y. Zgheib. All rights reserved.

Illustration copyright ©Antoine de Saint-Exupery from Le Petit Prince.

Illustration copyright ©2014 Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com