African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960 – Excerpt from Andy Fry’s “Paris Blues” (part one)

29 Tuesday Jul 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Cultures

Tags

African American music in France, African American musicians in France, Andy Fry King's College London, Bessie Smith jazz, Casino de Paris, Cotton Club Harlem jazz, Django Reinhardt Paris jazz, Duke Ellington, Folies-Bergère Paris, France, Guthrie P Ramsey Jr The Amazing Bud Powell: Black Genius Jazz History and the Challenge of Bebop, jazz age France, Jazz Age Paris, Josephine Baker Paris, Louis Armstrong, Ma Rainey jazz, Oxford London, Paris, Paris Blues Diahann Caroll Sidney Poitier Martin Ritt, Paris Blues Sidney Poitier Paul Newman Diahann Carroll Joaane Woodward Martin Ritt, Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture 1920-1960 Andy Fry, Ronald Radano University of Wisconsin-Madison, Sidney Bechet Paris jazz, Sunset Cafe in Chicago Jazz, The University of Chicago Press, Universities of Lancaster Berkeley Calaifornia, University of Berkeley, University of California San Diego, University of Pennsylvania

Share it

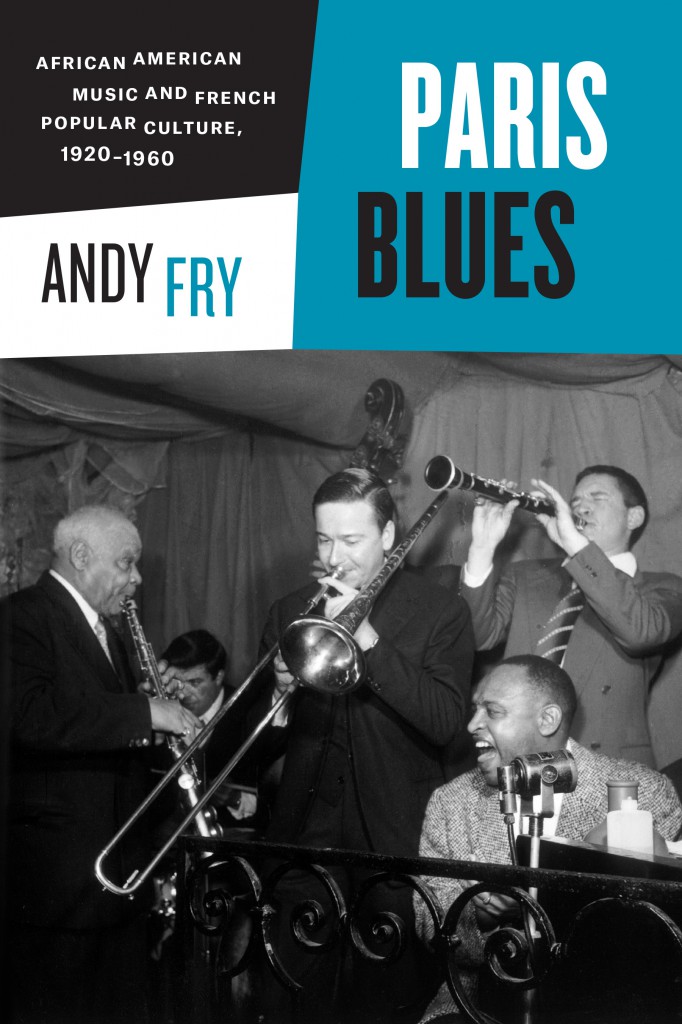

Reprinted with permission from Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960, by Andy Fry. Published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2014 The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960, by Andy Fry. Published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2014 The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Subscribers, copies of Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960 by Andy Fry. Free book giveaway to two subscribers ends August 14, 2014. A $30 U.S. value.

Subscribe free. Once subscribed, you will be eligible to win—no matter where you live worldwide—no matter how long you’ve been a subscriber. You can unsubscribe at anytime. We never sell or share member information.

The Jazz Age. The phrase conjures images of Louis Armstrong holding court at the Sunset Cafe in Chicago, Duke Ellington dazzling crowds at the Cotton Club in Harlem, and stars like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey wailing the blues away. But the Jazz Age was every bit as much of a phenomenon in Paris, where the French public found their own heroes and heroines at the Folies-Bergère and Casino de Paris.

In Paris Blues, Andy Fry provides an alternative history of African American music and musicians in France, one that looks beyond familiar personalities and well-rehearsed stories. He pinpoints key issues of race and nation in France’s complicated relationship with jazz from the 1920s through the 1950s. While he deals with many of the traditional icons—such as Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, and Sidney Bechet—he asks how they came to be so iconic, and what their stories hide as well as what they preserve. Fry focuses throughout on early jazz and swing but includes its re-creation—reinvention—in the 1950s. Along the way, he pays tribute to forgotten traditions such as black musical theater, white show bands, and French wartime swing. Paris Blues provides a nuanced account of the French reception of African Americans and their music and marks an important intervention in the growing literature on jazz, race, and nation in France. (Purchase)

INTRODUCTION: Part One (Part Two)

FIGURE I.1. Connie (Diahann Carroll) and Eddie (Sidney Poitier), Paris Blues, dir. Martin Ritt (1961).

EDDIE. Look, here [in Paris] nobody says Eddie Cook, Negro musician. They say Eddie Cook, musician, period. And that’s all I wanna be. [. . .] Musician, period. And I don’t have to prove anything else.

CONNIE. Like what?

EDDIE. Like, because I’m Negro I’m different, because I’m Negro I’m not different. I’m different, I’m not different, who cares? Look, I don’t have to prove either case. Can you understand that? [. . .]

CONNIE, shouting. Eddie, you’re wrong, you’re wrong. [. . .] Things are much better [in the United States] than they were five years ago, and they’re gonna still be better next year. And not because Negroes come to Paris. But because Negroes stay home. [. . .]

EDDIE. Look, are we gonna stand here all day discussing this jazz?

FIGURE I.2. Eddie (Sidney Poitier), Ram (Paul Newman), Connie (Diahann Carroll), and Lillian (Joanne Woodward), Paris Blues, dir. Martin Ritt (1961).

The 1961 film Paris Blues is remembered primarily for its colorful score by Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn. [1] Louis Armstrong’s on-screen role as “Wild Man Moore” is less fondly recalled, though his character has greater depth than was often the case in his movies. “Duke, Satchmo were true heroes to all Parisians,” pronounced Ebony magazine; during filming, “they were feted and entertained lavishly by artists, poets, actors and intellectuals.” [2] On release of the movie, however, sister magazine Jet saw only “yet another example of Hollywood’s almost chronic inability to fully utilize superlative talent.” Although the producer, Sam Shaw, was “a man of progressive ideals and real integrity,” Jet said, Paris Blues “fail[ed] to reflect either the depth of his viewpoint or his superior taste and values.” [3] Sure enough, this tale of two American tourists (Joanne Woodward, Diahann Carroll) who fall for expatriate jazz musicians (Paul Newman, Sidney Poitier) is nobody’s best effort: its plot is wayward, its dialogue clunky, its performances mixed. But reactions in the black press, like Eddie and Connie’s conversation, are in line with a long tradition of viewing the French capital as a hospitable city for African Americans compared to the harsh realities of home.

Certainly, in the cellar bar where Ram and Eddie’s band play and mingle with the customers, mutual respect and interracial harmony resound. On a romantic level, however, color coding is enforced. Connie (Carroll), a “socially conscious” African American, prefers saxophonist Eddie Cook (Poitier) to trombonist Ram Bowen (Newman; fig. I.2). [4] Although Eddie enjoys freedom and respect in Paris, he will eventually agree to return to a United States that Connie assures him is transforming. Ram, on the other hand, will disappoint Connie’s white friend, Lillian (Woodward). An aspiring composer, whose quest to complete his Paris Blues is the film’s conceit, he decides at the last moment that he must remain in Paris for the sake of his Art.

A comparison with Harold Flender’s 1957 pulp novel, on which the film was loosely based, is instructive. [5] Eddie was originally the central character, not his Jewish bandmate Benny (who becomes the WASPish Ram). Lillian, a spinster chaperone for Connie, was a love interest for neither man. It is hardly a surprise that Hollywood would make Ram the hero, or that it would rejuvenate Lillian as his leading lady. The African American couple may be retained alongside, but their relationship is more or less desexualized, as was customary in Poitier’s films (the contrast between the couples is marked in fig. I.3). As if enacting the dynamic to which Eddie fears to return, Connie/Carroll is the viewer’s eye candy while Eddie/Poitier is allowed to pose no threat to him [sic]. According to Tyler Stovall, this shift from a black protagonist to a white hero means that “the film both documented the experience of African American musicians in Paris and also symbolized the reasons why the city remained a refuge from America.” [6] What the scenario put in question by embracing a black man’s story, in other words, narrative logic and Hollywood convention scrambled to reinstate.

Stovall neglects to point out, however, that the film also omits scenes in the book that deal quite bluntly with French attitudes to race. For Flender’s Eddie, Paris may be “the only place [he has] ever felt at home, accepted, a human being,” but, as the story progresses, his experience tarnishes somewhat. A succession of taxi drivers offer tirades against North Africans while insisting that “France is a democratic country. We don’t discriminate against Negroes, like they do in America.” And Eddie remembers how, when he first arrived in Paris, his warm welcome was less a matter of color blindness than of Negrophilia. [7] Where the book goes so far as to mention the Algerian situation and French anti-Semitism, no such issues cloud the tourist’s view of Paris offered by the film. [8]

To the extent that the race question still burns in the movie Paris Blues, it does so stateside. Can Eddie return to life as a Negro? How much has the country changed in the five years he’s been away? As Stovall and others have recognized, in this period African American success abroad ceased to be an automatic cause for celebration at home; it began to look suspiciously like an evasion of duty to the race. [9] But Eddie is not keen to hear Connie’s admonitions, reiterating his rather naive view of colorblind Paris (see the dialogue above). Explaining the film’s muted reception, actor Joanne Woodward seemed to agree: “If a picture has a bi-racial cast I guess it’s supposed to be a ‘problem’ picture. Well, there isn’t any problem in ‘Paris Blues.’ ” [10] In this sense, the film does not depict France as it actually was (or is), but rather as an idealized vision for the future of America. [11]

The occlusion of race is typical, I suggest, not only of fictional approaches to African Americans in Paris but also of many historical ones: these, too, use France to shine a light on America, while ignoring or downplaying its own “race problem.” Take, for instance, William Shack’s Harlem in Montmartre (2001), one of a number of evocative portrayals in print of black life in Paris. As the author explains, he came from “that generation of African Americans whose f rst images of France sprang from stories told by fathers who had served in that country . . . during the Great War.” These included “descriptions of the hospitality French citizens displayed” and a “refrain . . . that a ‘colored man’ . . . had to travel . . . to be recognized as ‘equal’ to a ‘white man.’ ” [12] In this Shack finds his motivating principle. Like Tyler Stovall, who earlier wrote his Paris noir “as a success story, without illusions or apologies,” “a political statement . . . given the tendency . . . to present blacks as failures or as a ‘problem,’ ” Shack provides a sympathetic account of African American musicians in Paris, primarily from their own reminiscences. [13] His book thus serves as a useful reminder of black Paris’s enduring power as a lieu de mémoire.

The familiar narrative goes something like this: African American entertainers first came to France as minstrels in the nineteenth century and cakewalkers around the turn of the twentieth (witness Debussy’s popular piano pieces “Golliwogg’s Cake-Walk” and “The Little Nigar”). During World War I, black servicemen earned a reputation for music as well as fighting, particularly James Reese Europe’s 369th “Hellfighters” Division (commissioned to order as “the best damn band in the United States Army”). [14] Hot on their tail, early jazz bands such as Louis Mitchell and his Jazz Kings helped France to celebrate victory; Will Marion Cook’s Southern Syncopated Orchestra was famously eulogized by conductor Ernest Ansermet. [15] In the twenties, African Americans could be heard in a variety of venues: exclusive black-run nightclubs in Montmartre such as Gene Bullard’s Le Grand Duc (where legendary singer Bricktop started out and where Langston Hughes once washed dishes); music-hall shows, importantly Josephine Baker’s (in)famous debut in La Revue nègre; cafes and nightclubs such as Le Boeuf sur le Toit, the favorite hangout of Jean Cocteau and friends (as several compositions again attest); and, not to forget the decade’s new phenomenon, les dancings. [16]

In the wake of the depression, the 1930s were quieter, Shack suggests. Yet some of the best musicians—Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Coleman Hawkins—visited, and the Hot Club de France was established to promote jazz, along with its famous Quintet featuring (almost) homegrown talents Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli. Less wellknown is the paradox of the Second World War: on the one hand, the few African Americans who remained were incarcerated in prison camps; on the other, their music, now naturalized, “blazed as never before.” For Shack, at least, jazz’s continued presence during the Nazi occupation signaled French resistance, particularly in the hands of the long-haired, zoot-suited youths known as zazous. [17] After the war, “Louis Armstrong’s gravelly voice symbolized as much Paris liberated as General Charles de Gaulle’s victory parade.” [18] So not only did African Americans experience a new freedom in France; remarkably they were also able to share it with the French.

Throughout his account, Shack, like many others, views the history of black music and musicians in Paris through rose-tinted spectacles. While it is useful in tracing the role of the American press in France in stoking up racial tensions, for example, it is naive in denying any role to the locals. “The French public’s intolerance of racial prejudice countered white Americans’ intolerance . . . of a color-blind French society,” he writes. [19]

In contrast, historian Ralph Schor, in his detailed studies of French immigration and the attitudes it engendered in the interwar period, argues that these egalitarian ideals for the fraternity of races coexisted with an everyday reality of racism. Foreigners were certainly a subject of debate: between 1919 and 1939 there were almost twenty thousand articles on the subject in the eight newspapers he surveyed, and more than three hundred books. [20]

Among the many—sadly familiar—issues Schor found addressed, housing was a particular concern, the blame for a lack of affordable accommodation landing squarely on foreigners. Other fears were that poor sanitation led to disease among immigrants, and poverty and inadequate social conditions to high levels of crime. Most important, there were cultural and physical differences French people were barely able to accept. The general public, Schor argues, spurred on by right-wing parties and the media, felt their society was exposed to “a serious sanitary and moral contamination.” Although, for some, foreign performers occupied a special position, for others, they were “signs of an irremediable decadence, such as that of the Roman empire invaded and put to death by the barbarians.” [21]

Their New World origins—and money—doubtless granted African Americans some privileges. Coming from segregated America to a country proud of its egalitarianism (albeit an aggressive colonizer), they were also bound to find France a relatively hospitable place. It was not a “discrimination-free environment,” however, as Schor’s analysis makes plain. [22] Accepting sources whose bias should be self-evident (wartime articles in the black press; recent, ghostwritten memoirs), Shack’s book is less a critical history than a nostalgic extension of the story—a compilation of tales sent back home of African American success abroad. Suspicions that such accounts are not telling the whole truth need not challenge one fact: if Harlem in Montmartre is in some ways a myth, it is a lasting and empowering one, which became a historical force in its own right.

Yet more than pedantry sounds the alarm. African Americans’ memories of France—themselves more mixed than has often been claimed—must surely be understood in dialogue with the varied forms of segregation, hostility, and violence faced at home; removed from that context, idealized views too easily become vehicles of French complacency. Even if there was little direct hostility, black appeal too often relied on exoticistracialist thinking that shouldn’t be perpetuated, as a number of authors have by now discussed. [23] More than all this, mythologizing France as a land of equality rings hollow these days. Recent years have seen a widespread reevaluation of assimilation—in terms both of the legitimacy of the policy and the success of the practice—in the face of rioting youths and a resurgent extreme right wing. As the country waits for its minority groups in the banlieues to erupt in protest once more against their cultural and economic disenfranchisement in the land of liberté, égalité, fraternité, this vision not only proves hard to sustain, it may also have become politically irresponsible. [24]

The apparent disconnect between cultural and sociopolitical history has been particularly well captured by Carole Sweeney in her book From Fetish to Subject. As rare as it is rich, Sweeney’s assessment of the problem warrants quoting at some length:

“The negrophile aesthetic valorisation of a particular version of blackness [in France in the early twentieth century] did not of course translate into enlightened political policies around race and cultural difference either domestically or in the colonised territories. . . . The widespread popularity of l’art nègre and le jazz hot in the clubs and salons of bourgeois Paris did not make fashionable Parisians aware of the 1919 Pan-African Congress in Versailles led by W. E. B. DuBois or the formation of the Union Inter-Coloniale in 1921. While black American jazz musicians and entertainers were lauded in Paris in the 1920s, in North Africa, for example, an anti-imperial rebellion, la Guerre du Rif, led by the outlawed Abdel El Krim, was brutally suppressed in 1925 by the French military supporting Spanish forces. As Josephine Baker, the living embodiment of modern primitivism, was taking Paris by storm with her music-hall hit chanson “J’ai deux amours” and her slave-chic attire, the Institut Pasteur hosted a conference on so-called racial hygiene that explained the public health problems of the immigrant population in France. Most striking of all perhaps is the fact that a popular cultural negrophilia existed alongside a gradual resurgence of aggressively xenophobic nationalism.” [25]

While the current book is not the place to consider instances of colonial unrest and repression, or conversely the progress of black internationalism and civil rights, I am concerned to locate the reception of African American musicians accurately in terms of the discourses that swirled around them: whether performers became directly aware of them or not, such issues and events as Sweeney mentions often influenced how they were perceived and discussed. A paradoxical effect of cosmopolitanism and internationalism is the provincialism and prejudice they generate as counterforce: these phenomena must surely therefore be understood in both polarities in order to grasp their historical significance.

Not that I intend in this book simply to contest the affirmative view of African Americans in France by reviving their “Paris blues” in any straightforward sense. Rather, what I hope to convey in these pages is something of the complexity of experience that the fi nest performers in that genre register, particularly by incorporating perspectives gleaned from French reception. I do not attempt to survey the history of black music and musicians in Paris over these forty-odd years. This is a project that has, by now, been attempted several times, and not only in narrative accounts such as Stovall’s and Shack’s. Ludovic Tournes, Jeffrey H. Jackson, and Matthew F. Jordan, among others, have attended in considerable detail to the geographical, technological, and institutional factors influencing jazz’s production and reception in France, as I discuss below. More useful than replicating this approach, I believe, is to offer a series of focused inquiries, which reflect on and engage with these broader narratives but also concentrate in detail on particular cultural events. Thus I pursue case studies of varying kinds (genres, individuals, a work), without attempting to tell a complete or continuous story. To as great an extent as possible, I shape the chapters as critical readings of performances, ones that remain present to a greater or lesser extent, and invite debate.

The five chapters of Paris Blues move broadly chronologically, beginning with two forgotten traditions of the 1920s and 1930s (revues nègres and white show bands), continuing through Josephine Baker’s shows and films of the 1930s, and concluding with studies of jazz’s fortunes during the occupation and postwar years. Importantly, I consider the activities of nonblack musicians, whether American or European, in some detail, as well as African Americans performing music that could scarcely be understood as black. Despite extending as far as the 1950s, however, the book’s focus is early jazz and swing: its last chapter considers the revival—reinvention—of these musics alongside modern jazz, and the historiographical consequences of this phenomenon. As Paris Blues proceeds, then, it becomes increasingly concerned with the complex intersection of history and memory in the very story it tells. Without wishing to delimit their meanings, in the next section I locate these case studies loosely within the literature, suggesting how they may be understood to advance or intervene in scholarship that bridges several disciplines. [26] This should help readers to navigate the chapters, which may be read individually, or, as I hope, allowed to complement—and sometimes even contest—one another.

Praise for Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960

“Fry has combined meticulous research with careful and creative use of sources from the worlds of music, film, history and popular culture more generally to produce an account that might, finally, bury the perennial (and perennially misguided) idea that Europeans and especially the French understood and appreciated jazz before Americans did. The story is false not only because African American and other U.S.-based supporters of jazz seem not to be ‘Americans’ in that version of history, but also because, as Fry eloquently argues, the French at times tried to claim jazz as their own creation, because ethnocentrism and paternalism were rarely absent from what they wrote, because the music and the musicians were often proxies in debates over national culture, and because musicians had reasons for living in France that previous scholars have failed to describe completely.” — Travis Jackson, University of Chicago

“Andy Fry’s ardently interdisciplinary set of historical analyses of the ongoing importance of African American music in the cultural life of France introduces innovative perspectives on Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, and other major musical figures. This book incontrovertibly confirms the power of the new critical improvisation studies by affirming the centered place of music in any understanding of the human condition.” — George E. Lewis, author of A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music

Andy Fry joined King’s College London in 2007 having previously taught at the University of California, San Diego, and as a visiting professor at Berkeley, He completed his graduate studies at Oxford, D. Phil., and has also studied at the Universities of Lancaster, California (Berkeley), and Pennsylvania.

Paris Blues: Notes to pages 1 – 23

[1] Martin Ritt, dir., Paris Blues (Los Angeles: Optimum Classic, 2008), DVD.

[2] Anon., “Paris Blues,” Ebony 16/10 (August 1961): 46–50 (quote on p. 50).

[3] Allan Morrison, “Movie of the Week: Paris Blues,” Jet 21/6 (30 November 1961): 65.

[4] According to the film’s producer, Sam Shaw, the pairings were originally interracial (which is still suggested at the film’s opening), but the studio forced a switch. See David Hajdu, Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1996), 206–7; and Krin Gabbard, “Paris Blues: Ellington, Armstrong, and Saying It with Music,” in Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies, ed. Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 297–311 (esp. p. 302).

[5] Harold Flender, Paris Blues (New York: Ballantine Books, 1957; repr., London: Hamilton, 1961). Subsequent citations refer to the 1961 reprint.

[6] Tyler Stovall, Paris noir: African Americans in the City of Light (Boston: Mariner Books, 1996), 242.

[7] Flender, Paris Blues, 26, 66, 81.

[8] The movie also makes a telling substitution of the band’s guitarist. In Flender’s novel, he is a “French Negro” from a wealthy family who experiences a mental breakdown. Mystifying to the African American characters who think he’s had all the advantages they’ve lacked, his problems seem to result from the psychological violence of colonialism, compounded by the physical violence meted out by the French police. In the film, on the other hand, the guitarist is an altogether more familiar character, comprising two common tropes of jazz lore: “The Gypsy” looks like a member of Django Reinhardt’s extended family; he’s debilitated not by mental illness but by drug addiction (which, even at the time, critics found cliched).

[9] Stovall, Paris noir, 216–25, 244–50.

[10] William Leonard, “‘Paris Blues’ Change of Pace for Star,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 24 September 1961.

[11] An important context for Paris Blues is found in Poitier’s other films of the 1950s and 1960s, which saw him become the most successful African American actor of his time. All, in some sense, concern the struggle for integration but represent it among individuals: from Poitier’s assistance to an elderly priest (Canada Lee) in Cry, the Beloved Country (1952), through his allegiance to a fellow convict (Tony Curtis) in The Defiant Ones (1958), to the ground-breaking interracial romance (with Katharine Houghton) of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967). See, inter alia, Donald Bogle, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films, 3rd edition (New York: Continuum, 1997), 175–83, 215–19; and Thomas Cripps, Making Movies Black: The Hollywood Message Movie from World War II to the Civil Rights Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 284–94.

[12] William A. Shack, Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story between the Great Wars (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), xiii. A distinguished Berkeleyanthropologist, Shack left Harlem in Montmartre unfinished at the time of hisdeath. See my article “Beyond Le Boeuf: Interdisciplinary Rereadings of Jazz inFrance,” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 128 (2003): 137–53, on which I draw tosome extent in this introduction. Among earlier accounts, see Chris Goddard, Jazz Away from Home (New York: Paddington Press, 1979); and Bill Moody, The Jazz Exiles: American Musicians Abroad (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1993).

[13] Stovall, Paris noir, xv–xvi. A generation younger than Shack, Stovall dedicateshis book to the memory of his grandfather, who also served as a soldier inFrance during the First World War. Although, personally, Paris “never impressed[Stovall] as a paradise of racial good feelings” (xv), this is still basically the storyhe tells. His recent writings, however, have been more critical. See, for example, Tyler Stovall, “Black Community, Black Spectacle: Performance and Race in Transatlantic Perspective,” in Black Cultural Traffic: Crossroads in Global Performance and Popular Culture, ed. Harry J. Elam Jr. and Kennell Jackson (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005), 221–41; and Stovall, “No Green Pastures: The African Americanization of France,” in Black Europe and the African Diaspora, ed. Darlene Clark Hine, Trica Danielle Keaton, and Stephen Small (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 180–97.

[14] Colonel William Hayward, cited in Shack, Harlem in Montmartre, 14. For recent accounts, see R. Reid Badger, A Life in Ragtime: A Biography of James Reese Europe (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); and Colin Nettelbeck, “A Different Music: Jazz Comes to France,” in Dancing with DeBeauvoir: Jazz and the French (Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, 2004), 16–30.

[15] Ernest Ansermet, “Sur un orchestre negre,” in Écrits sur la musique (Neuchatel, Switz.: Baconniere, 1971), 171–78. This much-cited and commonly reproduced text was fi rst published in La Revue romande 3/10 (October 1919), then reprinted, with an English translation by Walter E. Schaap, in Jazz hot, no. 28 (November–December 1938): 4–9. Among other locations, it is available in English in Ralph de Toledano, ed., Frontiers of Jazz (New York: Oliver Durrell, 1947), 115–22; and in Robert Walser, ed., Keeping Time: Readings in Jazz History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 9–11. I discuss Ansermet’s review at some length in chap. 5 below.

[16] See Craig Lloyd, Eugene Bullard: Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000); Bricktop [Ada Smith], Bricktop, with James Haskins (New York: Atheneum, 1983); and Langston Hughes, The Big Sea (New York: Hill and Wang, 1933). On Baker, see chap. 3 below. On Cocteau, see, in addition to texts cited later in this introduction, Francis Steegmuller, Cocteau: A Biography (London: Macmillan, 1970); and Jann Pasler, “New Music as Confrontation: The Musical Sources of Jean Cocteau’s Identity,” Musical Quarterly 75 (1991): 255–78.

[17] Shack, Harlem in Montmartre, 117. See Matthew F. Jordan, “Zazou dans le Métro: Occupation, Swing, and the Battle for la Jeunesse,” in Le Jazz: Jazz and French Cultural Identity (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 185–232.

[18] Shack, Harlem in Montmartre, 124.

[19] Ibid., 67

[20] Ralph Schor, L’Opinion française et les étrangers en France, 1919–1939 (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 1985); Schor, Histoire de l’immigration en France, de la fin du XIXe siècle à nos jours (Paris: Armand Colin, 1996). The newspapers surveyed were L’Action française, Le Temps, La Croix, L’Aube, L’OEuvre, Le Populaire, Le Peuple, and L’Humanité.

[21] Schor, Histoire de l’immigration, 90, 117.

[22] Shack, Harlem in Montmartre, xvi (quote); Schor, L’Opinion française; and Schor, Histoire de l’immigration.

[23] See, for example, Petrine Archer-Straw, Negrophilia: Avant-Garde Paris and Black Culture in the 1920s (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000); Brett A. Berliner, Ambivalent Desire: The Exotic Black Other in Jazz-Age France (Amherst: University ofMassachusetts Press, 2002); and Elizabeth Ezra, The Colonial Unconscious: Race and Culture in Interwar France (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000).

[24] See, for example, Trica Danielle Keaton, “‘Black (American) Paris’ and the French Outer-Cities: The Race Question and Questioning Solidarity,” in Hine, Keaton, and Small, Black Europe and the African Diaspora, 95–118; and Fred Constant, “Talking Race in Color-Blind France: Equality Denied, ‘Blackness’ Reclaimed,” in ibid., 145–60. See also Sue Peabody and Tyler Stovall, eds., The Color of Liberty: Histories of Race in France (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003); and Trica Danielle Keaton, T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, and Tyler Stovall, eds., Black France / France Noire: The History and Politics of Blackness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press,2012).

[25] Carole Sweeney, From Fetish to Subject: Race, Modernism, and Primitivism, 1919–1935 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004), 2–3.

[26] At the risk of sounding contrite or, worse, complacent, it may be worth noting that the early chapters of this book were researched and drafted prior to the publication of much of the literature I will discuss here. While I have integrated these authors’ insights to as great an extent as possible, the relationship between their texts and mine remains a somewhat oblique one, simply because theirs was not the context in which I conducted my research.

A Woman’s Paris® is a community-based online media service, bringing fresh thinking about people and ideas that shape our world and presents a simplicity and style, in English and French.

Connecting with you has been a joyous experience—especially in learning how to enjoy the good things in life. Like us on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter. Share us with your friends.

Barbara Redmond

Publisher

barbara@awomansparis.com

Text copyright ©2014 University of Chicago Press. © Andy Fry. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com