French Impressions: Barbara Will on Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and intellectual life during wartime France (part one)

07 Tuesday Jan 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Interviews

Tags

Alice B. Toklas, American Council of Learned Societies, American GIs, American Philosophical Society, August is a Wicked Month Edna O'Brien, Barbara Will, Bryn Mawr College, Camargo Foundation Cassis France, Choice Outstanding Academic Title award, Dartmouth College, Dora Bruder Patrick Modiano, Duke University, French Resistance, French Resistance World War II, Gertrude Stein, Gertrude Stein Modernism and the Problem of Genius, Gertrude Stein Nadine Satiat, Henri Matisse, Jewish Ideas Daily, Leo Stein, Marshal Philippe Pétain, Michael Stein, Mrs Reynolds Gertrude Stein, National Endowment for the Humanities, Nazi occupiers France, Pablo Picasso, Samuel Beckett, The American Woman in the Chinese Hat Carole Maso, The Melancholy of Resistance László Krasznahorkai, The New Republic, The Stein's Collect Matisse Picasso and the Parisian Avant-Garde, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein Bernard Faÿ and the Vichy Dilemma, Vichy regime France, Wars I Have Seen Gertrude Stein, World War I, Yale University

Share it

(French) Barbara Will, professor of English at Dartmouth College, was educated at Yale University (B.A.), Bryn Mawr College (M.A.), and Duke University, where she received her Ph.D. in Literature in 1992. Before coming to Dartmouth, she taught at the University of Geneva in Switzerland and has also been a visiting professor at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. Professor Will has published widely on twentieth-century literature and culture, and is a specialist on the writer Gertrude Stein. Her book, Gertrude Stein, Modernism, and the Problem of “Genius” (Edinburgh UP, 2000), explores Stein’s complex relationship to her own creative authority, and situates her in the broader context of modernist literature. This book won the 2001 Choice Outstanding Academic Title award.

(French) Barbara Will, professor of English at Dartmouth College, was educated at Yale University (B.A.), Bryn Mawr College (M.A.), and Duke University, where she received her Ph.D. in Literature in 1992. Before coming to Dartmouth, she taught at the University of Geneva in Switzerland and has also been a visiting professor at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. Professor Will has published widely on twentieth-century literature and culture, and is a specialist on the writer Gertrude Stein. Her book, Gertrude Stein, Modernism, and the Problem of “Genius” (Edinburgh UP, 2000), explores Stein’s complex relationship to her own creative authority, and situates her in the broader context of modernist literature. This book won the 2001 Choice Outstanding Academic Title award.

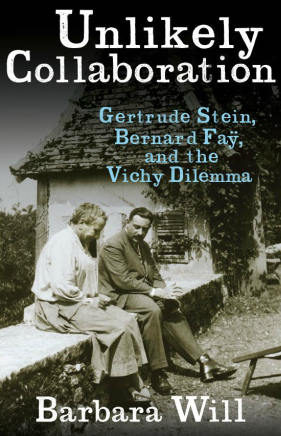

Her second book, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, received major research awards from the American Council of Learned Societies, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Philosophical Society, and the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France. She is currently at work on a new project on Irish writer Samuel Beckett and his involvement with the French Resistance during World War II. For more information on Barbara Will, visit: (Website) (Purchase)

Her second book, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, received major research awards from the American Council of Learned Societies, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Philosophical Society, and the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France. She is currently at work on a new project on Irish writer Samuel Beckett and his involvement with the French Resistance during World War II. For more information on Barbara Will, visit: (Website) (Purchase)

“A fine-grained, unflinching, and nuanced history.” — New York Review of Books

“Brilliant and fascinating… This exceptional study provides new insights into previously hidden corners of Stein’s life.” — Publishers Weekly (starred review)

INTERVIEW

Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma

From 1941 to 1943, Jewish American writer and avant-garde icon Gertrude Stein translated for an American audience thirty-two speeches in which Marshal Philippe Pétain, head of state for the collaborationist Vichy government, outlined the Vichy policy barring Jews and other “foreign elements” from the public sphere while calling for France to reconcile with its Nazi occupiers. Why and under what circumstances would she undertake such a project? The answers lie in Stein’s link to the man at the core of this controversy: Bernard Faÿ, her apparent Vichy protector. Barbara Will outlines the formative powers of this relationship, treating their interaction as a case study of intellectual life during wartime France and an indication of America’s place in the Vichy imagination.

AWP: You are the author of Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma. What inspired you to write this book?

BW: I was inspired by the complexity of the issue. A Jewish-American and experimental writer drawn to an authoritarian regime—a regime complicit with Hitler and the Nazis. The sheer incongruity of this story seemed well worth exploring in a book.

AWP: You entrench your book in a different part of Gertrude Stein’s past, taking stock of her life as a woman and writer, as well as her work as a collaborator in the Vichy regime translating Marshal Philippe Pétain’s writings for an American audience. What challenges did you encounter, and how did you unfold the story you wanted to tell?

BW: The challenges were intellectual and professional—going into the archives, doing the research that would uncover the facts about Stein’s past and the past of her friend Bernard Faÿ, determining which sources were reliable and which were not, poring over innumerable primary documents, including many written in German and French. I found myself becoming an expert not only on Stein’s life, but also on France during the Vichy regime (and the years leading up to it), on Nazism, and on the concerns that preoccupied Stein’s friend Faÿ: namely, Catholicism and its struggle against Freemasonry.

But the challenges were also personal. The book forced me to find my way through complex, morally ambivalent issues. Writing it was a struggle. To this day I remain fascinated by Gertrude Stein’s writing and convinced of the originality of her art. I had made this originality the subject of my first book, Gertrude Stein, Modernism, and the Problem of “Genius.” Yet my second book on Stein, Unlikely Collaboration, forced me to question what it meant that such a great writer was also such a compromised person. I now think of Stein as basically rather weak: coddled, immature, and selfish—traits that come out in force during the hellish years of the Vichy regime. At the same time, I continue to be amazed by ways in which she was actually very strong—particularly in her courage to live her life openly as a lesbian during a closeted time. In the end, she’s not only a brilliant artist but also a deeply complex person, and I hope my work on her does justice to this complexity.

AWP: Gertrude Stein seems the least likely person to write propaganda in support of an authoritarian regime. What was she doing translating these speeches of Pétain into English? How do we make sense of Stein’s perverse translation project?

BW: There were a couple of factors involved in this translation project. The first was Stein’s own interest in Philippe Pétain, head of state of the pro-Nazi Vichy regime. Stein had long been fascinated by Pétain, whom she saw as the ideal leader for a France weakened by “decadence” after the turbulent era of the 1930s. Like many others in France, Stein welcomed the armistice with the Nazis in June of 1940 and saw Pétain as a “savior” for avoiding war. She seems to have been swayed by his own propaganda portraying him as a saint and a neo-Joan of Arc who would offer France a new future. Yet Stein apparently believed in Pétain long after the rest of the country had written him off—believed in him enough to volunteer to become a propagandist for his regime. The translation project was part of this propaganda.

The second factor was the influence of Stein’s friend Bernard Faÿ. My book suggests that Stein’s friendship with Faÿ (who was himself an intimate of Pétain as well as a Gestapo agent during World War II) ultimately led her into the inner circle of Vichy. Doing the translation project allowed Stein to cement her privileged place in the Vichy regime.

AWP: French writer, translator, historian, and art patron Bernard Faÿ was a central figure in Pétain’s Vichy regime. Why did you choose to tell Stein’s support of the Vichy regime though her relationship with Faÿ?

BW: Two more fascinating individuals have rarely breathed the same air! We know a lot about Stein and her friends, her famous art collection, her exciting expat literary salon, her incredible experimental writing, the scene around her in Paris in the first half of the twentieth century. But practically no one has ever heard of Bernard Faÿ, and in many ways he was just as colorful as Stein herself. Highly erudite, an impeccable writer in both French and English, a lover of all things American, the first Professor of American Studies in France, the youngest person ever elected to the Collège de France, friend of Franklin Roosevelt, Philippe Pétain, even Heinrich Himmler—Bernard Faÿ is an utterly unique character. He also had an enormous influence on Stein’s political views. I knew that telling their story jointly would make for a much better narrative.

AWP: In their relationship during the early years of World War II, did Stein and Faÿ believe they were framers of a new era? Do we know their shared “truths”? Were they caught in their own web of self-proclaimed “genius” or did they see themselves as historical interpreters, thereby influencing events around them?

BW: These are great questions. In a certain inverted way both did see themselves as “framers of a new era,” although their “new era” would always be a retro one. Certainly both saw themselves as clear-eyed interpreters of their era. Both were profoundly reactionary. Both wanted to return to the past, to a past lost to the epoch of “modernity.” “Modernity”—particularly after World War I—was a code word for decadence. Returning to the past was a way of bypassing the problems of modernity, of starting over again. Their reactionary vision fit in perfectly with Philippe Petain’s vision of a “National Revolution” for France, of a return to the values of “travaille, famille, patrie” that had been lost during the supposedly decadent era of the 1930s.

AWP: 18th century America and France, in sense and time, seem central to the relationship between Stein and Faÿ, and were often considered by them as utopia. How do we understand this dichotomy between Stein the American writer and avant-garde icon and Stein the parochial 18th century romantic? What did the 18th century imply for them?

BW: American modernist writers—even the most experimental ones—often look back nostalgically to premodern eras. I think of T.S. Eliot and his reverence for early orthodox Christianity; of Ezra Pound and his love of medieval romance and the concept of “virtu;” of Ernest Hemingway and his fascination with the American frontier. One has to understand that much of this nostalgia emerged after these expatriate American writers escaped to the “old world,” removing themselves from the environment of American modernity.

For Gertrude Stein, the eighteenth-century was America’s prelapsarian moment, when the still unformed nation was at its most democratic, its leaders at their most vital. She actually saw her own writing as containing some of this eighteenth-century vitality. Meeting Bernard Faÿ in the late 1920s was significant for her. Faÿ was the foremost scholar on the American eighteenth century in France, and he and Stein immediately agreed on the importance of this historical epoch. This cemented their friendship, and nurtured their shared reactionary beliefs.

AWP: How tight was their power grip on one another? Could one exist without the other or in the end did one exert the upper hand?

BW: I tell the story of their friendship in terms of an arc of power, since both were fascinated by power, ambition and success. In the beginning, Stein clearly had the upper hand: she was older than Faÿ by some two decades, and had a major cultish reputation when Faÿ stepped into her orbit. As the 1930s and 40s progressed, Faÿ’s political star began to rise and Stein began to grasp what a valuable friend he was. Faÿ was also one of Stein’s principal translators, and was thus helping her career in other ways as well. During World War II, Faÿ’s influence and importance was at its highpoint and Stein was at her most vulnerable. Then once again the tables turned at the end of the war. After Faÿ was sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor, Stein again became the magnanimous supporter of a less powerful, indeed weakened friend.

If Stein had never met Bernard Faÿ, would she have remained in France in the late 1930s as the political scene heated up and as her friends and family left for safer places? I highly doubt it. Faÿ had an enormous influence over Stein during the last two decades of her life. And after she died in 1946, a bereft Faÿ referred to her as “one of the few authentic experiences of my life.”

AWP: Stein agreed to translate a set of speeches by Marshal Philippe Pétain. Were they ever published in America?

BW: No. They never saw the light of day until a graduate student in the 1990s began asking hard questions about them. Even today they’re still unpublished, sitting in a folder in Beinecke Library at Yale University.

AWP: During the Occupation, how were Stein and Toklas able to escape the purge of Jews from wartime France? Did Bernard Faÿ have a hand in their protection? Did Stein receive privileges as an American writer working for French propaganda in America?

BW: The only source that attempts to address these questions is Bernard Faÿ’s own admittedly self-serving memoir Les Précieux, in which he states that he did indeed intervene to protect Stein and Toklas during the war. Many unanswered questions remain, however, and I spend much of the latter half of my book parsing out what we can know about Stein’s actual experience.

AWP: Did Stein support Faÿ in his postwar trial? Were there any cases brought against Gertrude Stein after the Liberation?

BW: Stein wrote a letter in support of Bernard Faÿ for his trial. It is a rather lukewarm document, although Faÿ made much of it in his effort to prove publically that he was not an anti-semite. Stein herself was never called out for her wartime propaganda efforts. After the war ended she was discovered alive in the south of France by American GIs and journalists, hailed in the American press as a survivor, and died shortly thereafter in 1946.

AWP: Was Stein’s translation of Pétain’s speeches literal and sophomoric or did she impart her own “spin” to his Vichy policies?

BW: The literalism of Stein’s translations is fascinating. I speculate that this has to do with the thwarted nature of the project. Stein was never a conventional translator, and the Pétain translation project seemed to demand a certain allegiance to the dictator’s words. In the end, Stein simply translated Pétain’s speeches word-for-word. The effect is atrocious.

AWP: Did Stein translate other political works, speeches, essays, manifestos, by others in the regime?

BW: No. In correspondence during the second year of the Vichy regime, Stein referred to herself as a propagandist for France, but apart from the Petain translation project and another pro-Petainist piece she published in the Vichy journal La Patrie, she produced no other propaganda for the regime. So really she left very few traces of her Pétainist views, though my book discusses a whole series of uncomfortable comments she made before, during, and after the war.

AWP: Did Stein play a similar part in the French Resistance waging bets on the war’s outcome?

BW: Again, her connections to the Resistance seem to have been more fortuitous than by design. The region in which Stein was living during the war—the Bugey, in the southwestern part of France—was a hotbed of maquis activity after 1942. Stein had no great love for the Nazis—her ties were toward Pétain, not the Nazis—and she clearly enjoyed seeing the maquis sabotage Nazi strongholds. By the end of the war, like many others, Stein played up her ties to the Resistance, and played down her ties to Pétain.

AWP: Collaboration is a serious charge: a term, as you write, that belongs in a black and white world. How do we understand the term collaboration in the grey-zone of life in France during World War II? Are there subtle differences in the ways people of France interacted with their Nazi occupiers?

BW: Yes, and the point of my book is to lay out these subtle differences. Both Faÿ and Stein could be called collaborators; both have been called collaborators—Faÿ, officially, by a postwar Vichy purge trial; Stein, unofficially, by a number of readers and historians who consider her Pétainist propaganda to be collaboration pure and simple. Both supported the Vichy regime; both also had their disagreements with it. Before we pass judgment on them, we need to place their actions within a larger context, within an era aptly described by Hannah Arendt as a “death world.”

AWP: How have you been able to find a way of telling this story so that what people feel isn’t hatred or despair, but the larger sense of the fragility of life?

BW: We are all complex people, and some of us have the good fortune to live during a time that does not force us to question the very limits of our convictions, our courage. I am drawn to thinking about those more trying times because I want to ponder the difference between certain variables: choice and chance, action and reaction, self-preservation and sacrifice. And at the end of my book, I do affirm and celebrate the fact of survival.

AWP: Your research is exemplary. How did you accumulate and obtain this information? From civil and court records, memoirs, letters, eyewitnesses, among others? Was the information primarily in French?

BW: I probably should have been a professor of history: I have always been fascinated by archives, by the thrill of finding something in a dusty box that opens up a whole world. There were lots of dusty boxes in the making of my book. Many of them were housed in the Stein archives at Yale University and in the Faÿ archives at the Archives Nationales in Paris. I also had the good fortune to meet several of Faÿ’s living relatives, students, and friends, who kindly shared with me insight and materials that brought the man to life. Stein was already a vivid person to me from my previous work on her writing, much of which is highly autobiographical. Yet breaking down the masquerade of the persona she developed in her later life took some doing. Since she never wrote anything about her Vichy propaganda, I had to uncover this material in the gaps and silences of her life (as well as in the dusty archives of her friends and contemporaries).

AWP: Have we now just come to know of Stein’s translations of Pétain’s policies?

BW: No, the story of how those translations became well known is an interesting but tragic one. Stein scholars had long known about her Pétainism, and a few had addressed, in general terms, the possibility of a translation project. But it wasn’t until 1996, when an intrepid graduate student named Wanda van Dusen found Stein’s translations of Petain’s speeches in a folder in the archives at Yale University, that the full extent of Stein’s propaganda activities came to light. Van Dusen published both the introduction that Stein wrote to accompany the speeches, which was highly praiseworthy of Pétain, and a brief analysis of Stein’s politics that raised many of the same questions I address in my book. Sadly, van Dusen took her own life shortly after bringing these materials to light. Her work was truly pathbreaking.

AWP: What was the most surprising thing you learned about World War II from the historian’s distance of nearly sixty years since its end?

BW: What I call the “grey area” of this period. We are so used to a simplistic, good vs. evil view of World War II and the people who lived through it. While that view importantly allows for the horror of the war to remain vivid, it also ironically distances us from that moment. Only by looking at the complexity of what it must have been like to live through this “death world” can we really put ourselves back in the shoes of those who experienced it.

AWP: Did Stein write of any sense of personal culpability for choosing to support the Vichy regime and its ideology?

BW: No, and surprisingly, she defended Pétain up to the end of the war.

AWP: Why is this message of her involvement significant, especially today?

BW: My book is above all a journey into the “death world” of World War II. It shows how deeply fascism divided and severed human beings from one another, creating invidious, dehumanizing racial, national, and religious distinctions. The story of Stein and Faÿ’s friendship captures in microcosm the shape of this era. It covers the terrain of modernist art, French-American relations, and European politics, but it does so through the lens of these two outsize individuals and their particular perspectives on the world around them. It is a compelling personal story, but it is also the story of one of the most significant and unsettled epochs in modern history. Those who write about this period know that we do so in order to keep it at bay.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post French Impressions: Dr. Alan T. Marty on the dark history of the City of Light. Alan T. Marty, MD, armed with an historically-informed exploratory spirit, has often encountered Paris’ endless capacity to evoke a mood, to surprise with similar absent/present paradoxes, as detailed in his A Walking Guide to Occupied Paris: The Germans and Their Collaborators, a book-in-progress. His work has been acknowledged in Paris dans le Collaboration by Cecile Desprairies, Hal Vaughan’s book Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War; and referenced in Ronald Rosbottom’s When Paris Went Dark, and in an upcoming book about Occupied Paris by Tilar Mazzeo.

Stars, Stripes and Seine: Americans in occupied Paris 1940-1944, by Alan Davidge. 5,000 Americans refused to leave Paris after war broke out in September 1939. Who were they? Read the stories of how Josephine Baker, Sylvia Beach, Arthur Briggs, Drue Leyton, and others lived and breathed Paris during the war.

D-Day Travel Guide: For American visitors to Normandy, France, by Alan Davidge, D-Day tours historian, Normandy. Alan has managed to seek out a number of places of significance that do not usually feature in guidebooks. Guides included.

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2014 Barbara Will. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com

1 comments

Alan Davidge said:

January 10, 2014 at 2:32 pm

Sounds a fascinating book. I did some research on the activities of Americans in Paris during the war which led to an AWP article last year and this tackles the subject in so much depth. I live in Normandy and am surrounded every day by reminders of what took place here 70 years ago.

As history, it’s far from simple however as the war must have divided the country as much as the US Civil War (but not being an American it’s probably not for me to say!). Pétain obviously carried a lot of charysma from his heroics at Verdun and having witnessed the horrors of war first hand, he didn’t want to see it all happen again. If he had a crystal ball, he may have chosen differently, as would his admirers.

Some of the French have long memories however. A house near us was occupied by Rommel for a while and I know of one old villager who will not set foot over the threshold!

Hope to read the book.

Alan Davidge