French Impressions: Barbara Will on Gertrude Stein’s excess in writing, thinking, and being (part two)

09 Thursday Jan 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Interviews

Tags

Alice B. Toklas, American Council of Learned Societies, American GIs, American Philosophical Society, August is a Wicked Month Edna O'Brien, Barbara Will, Bryn Mawr College, Camargo Foundation Cassis France, Choice Outstanding Academic Title award, Dartmouth College, Dora Bruder Patrick Modiano, Duke University, French Resistance, French Resistance World War II, Gertrude Stein, Gertrude Stein Modernism and the Problem of Genius, Gertrude Stein Nadine Satiat, Henri Matisse, Jewish Ideas Daily, Leo Stein, Marshal Philippe Pétain, Michael Stein, Mrs Reynolds Gertrude Stein, National Endowment for the Humanities, Nazi occupiers France, Pablo Picasso, Samuel Beckett, The American Woman in the Chinese Hat Carole Maso, The Melancholy of Resistance László Krasznahorkai, The New Republic, The Stein's Collect Matisse Picasso and the Parisian Avant-Garde, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein Bernard Faÿ and the Vichy Dilemma, Vichy regime France, Wars I Have Seen Gertrude Stein, World War I, Yale University

Share it

(Part one) Barbara Will, professor of English at Dartmouth College, was educated at Yale University (B.A.), Bryn Mawr College (M.A.), and Duke University, where she received her Ph.D. in Literature in 1992. Professor Will has published widely on twentieth-century literature and culture, and is a specialist on the writer Gertrude Stein. Her book, Gertrude Stein, Modernism, and the Problem of “Genius” (Edinburgh UP, 2000), explores Stein’s complex relationship to her own creative authority, and situates her in the broader context of modernist literature. This book won the 2001 Choice Outstanding Academic Title award.

(Part one) Barbara Will, professor of English at Dartmouth College, was educated at Yale University (B.A.), Bryn Mawr College (M.A.), and Duke University, where she received her Ph.D. in Literature in 1992. Professor Will has published widely on twentieth-century literature and culture, and is a specialist on the writer Gertrude Stein. Her book, Gertrude Stein, Modernism, and the Problem of “Genius” (Edinburgh UP, 2000), explores Stein’s complex relationship to her own creative authority, and situates her in the broader context of modernist literature. This book won the 2001 Choice Outstanding Academic Title award.

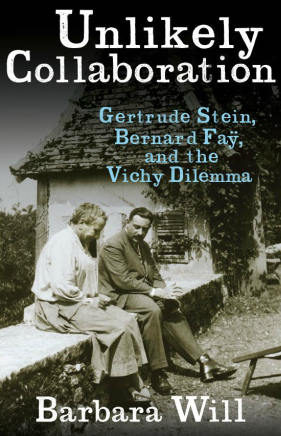

Her second book, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, received major research awards from the American Council of Learned Societies, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Philosophical Society, and the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France. She is currently at work on a new project on Irish writer Samuel Beckett and his involvement with the French Resistance during World War II. For more information on Barbara Will, visit: (Website) (Purchase)

Her second book, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, received major research awards from the American Council of Learned Societies, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Philosophical Society, and the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France. She is currently at work on a new project on Irish writer Samuel Beckett and his involvement with the French Resistance during World War II. For more information on Barbara Will, visit: (Website) (Purchase)

“[An] absorbingly detailed and even-handed book.” — The New Republic

“Extremely detailed and erudite.” — Jewish Ideas Daily

INTERVIEW (part two)

Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma

From 1941 to 1943, Jewish American writer and avant-garde icon Gertrude Stein translated for an American audience thirty-two speeches in which Marshal Philippe Pétain, head of state for the collaborationist Vichy government, outlined the Vichy policy barring Jews and other “foreign elements” from the public sphere while calling for France to reconcile with its Nazi occupiers. Why and under what circumstances would she undertake such a project? The answers lie in Stein’s link to the man at the core of this controversy: Bernard Faÿ, her apparent Vichy protector. Barbara Will outlines the formative powers of this relationship, treating their interaction as a case study of intellectual life during wartime France and an indication of America’s place in the Vichy imagination.

AWP: Why did Gertrude Stein and her partner Alice B. Toklas, unlike so many Jews, choose to remain in a situation that was clearly life-threatening? Did Stein know what was happening to others during her support of Pétain’s National Revolution and actual Vichy propaganda?

BW: Those questions are extremely hard to answer, because we have very little evidence about what Stein and Toklas were thinking during the war. Correspondence is thin, and whenever Stein writes to anybody her comments are highly veiled. We do have a novel Stein wrote during the war called Mrs. Reynolds that obliquely describes the terrors of life during wartime. We have a few dark, weird children’s stories she wrote between 1940-1943. We also have an autobiography that Stein published immediately after the war called Wars I Have Seen. In it Stein states that life was difficult for her and her neighbors in the Bugey, but she never explicitly differentiates her own experiences as a Jewish woman from any of her neighbors’ experiences. She also continues to praise Philippe Pétain for having “achieved a miracle” with the Armistice (this, after Pétain had been sentenced to death by a French court for treason).

Given the close neighborly ties Stein describes in this book, I find it hard to believe that Stein didn’t know what was happening to the Jewish neighbors around her. Her silence is deafening.

At the same time, it’s worth noting that Stein’s sense of the situation may have changed over the course of this long and fraught conflict. While Stein seems to have supported Pétain throughout the war, she also made friends with some members of the French Resistance (the maquis) who were living in her region during the last months of the war. Like many people in France during this whole uncertain time, Stein kept alive contradictory allegiances until the outcome of the war forced clear lines to be drawn.

AWP: Gertrude, her brothers, Leo and Michael, and Michael’s wife, Sara, were early collectors of works by painters like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse; much of it was acquired before the First World War. How and why did this art survive the war, specifically the art in Gertrude’s collection?

BW: This was a major, contentious issue that emerged during the recent exhibit of the Stein family art collection that toured San Francisco, New York, and Paris. The exhibit was called “The Stein’s Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde.” Many people who saw the exhibit, particularly in New York, questioned how those great art works by Matisse and Picasso managed to remain in Gertrude’s possession when the collections of so many other Jewish people were confiscated and hoarded as “degenerate” by Nazi and Vichy officials. Here the influence of Bernard Faÿ in Gertrude’s life was significant.

There is a story that near the end of the war, Vichy officials decided to enter Stein and Toklas’s apartment on rue Christine in Paris. The apartment had been sealed when the two women fled to the south of France in 1939. Picasso got wind of this news and—fearing the worst for his paintings—contacted Faÿ, who intervened with the authorities to leave the apartment undisturbed. My gut feeling is that there were other moments like this during the war when Faÿ stepped in to protect Stein’s collection. In his Vichy years, Faÿ spent a lot of time trying to safeguard French cultural treasures from being hoarded by the Nazis; this is what he knew how to do, and he did it for Gertrude as well.

AWP: Do we give freedom to intellectuals whose work we admire, regardless of the context in which it was created or its intent? Should we judge them by higher ethical or moral standards?

BW: These are questions that permeate my book. I still don’t feel I can adequately answer them. If we continue to value the myth of the artist-genius (a very powerful myth indeed), then we cannot place too much emphasis on their context or the views they may have espoused during their life. Stein herself was very invested in this genius myth. Yet I remain deeply troubled by the idea that artists or intellectuals should be given a free pass simply because of their perceived brilliance or originality.

AWP: When you started writing Unlikely Collaboration, did you have a sense of what you wanted to do differently from other biographic accounts of Gertrude Stein?

BW: I had a strong sense that I was not going to try to excuse or explain away Stein’s political views. I did not want to write a hagiography. Having worked on Stein for many years, I knew that her reputation as a writer and innovator was robust enough that it could coexist with revelations about her life and views. The attraction of modernist writers to fascist regimes is also so widespread that I felt there was a significant gap in not including Stein in the discussion.

AWP: Had Stein lived, would she have been exiled from France or emerge unscathed by her support of Pétain?

BW: When she was discovered by American GI’s and journalists at the end of the war, she was widely hailed as a survivor—which she was, among other things. Her support for the Vichy regime was never discussed, beyond the comments of a few friends and acquaintances who had heard things during the war. In any case, after the war public attention in France was directed toward the “true” collaborators: people like Faÿ, who had profited enormously from the Vichy regime and who was put on trial for his actions in 1946.

AWP: What were the new demands placed on Gertrude Stein after her sudden celebrity and triumph of her book The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas? Did she feel suddenly displaced in the wake of her enormous success?

BW: The success that Stein experienced in the 1930s was both electrifying and ultimately distressing for her. My sense is that it made her deeply aware of the burdens and responsibilities of public figures. It was in the wake of her own great success in America that she began talking about the importance of political figures and the desire of the public to be led around by dictators.

AWP: Who or what championed Stein’s celebrity in America after the war; after her death in 1946?

BW: She became the darling of a certain kind of postwar American mass media—Life magazine, for example, featured her in a story about American GIs and their experience in postwar Europe. Before the war, in the 1930s, Stein had presented herself to the American public as a homespun American heroine caught up in the antics of zany Parisian modernism, and she played this role very well. After World War II she easily adopted that role again. She was savvy at manipulating American mass media and the burgeoning celebrity machine.

WRITING

AWP: You are also the author of Gertrude Stein, Modernism, and the Problem of “Genius” (2000). What is it about Stein’s humanity and position as a literary figure that motivates you when you are writing?

BW: I have always been interested in Stein’s writing and in what I can only call her excess: as a writer, as a thinker, as a person. Bernard Faÿ said that she had an enormous joie de vivre and he was right. Unfortunately, her unruliness or excess also led her toward some uncomfortable, morally ambivalent choices. We cannot celebrate one side of Stein and ignore the other.

AWP: How did your earlier book Gertrude Stein, Modernism, and the Problem of “Genius” influence your book Unlikely Collaboration?

Most profoundly, I think that Stein’s sense of herself as a genius played a large role in her identification with Philippe Pétain as a great general and leader. Her portrayal of Philippe Pétain in the introduction she wrote to his speeches shares a core vocabulary with her description of herself as a genius.

AWP: Tell us something we don’t know about Gertrude Stein or Alice B. Toklas.

BW: Alice Toklas may have held even more reactionary political views than Gertrude Stein.

AWP: Gertrude Stein is an American icon, but is she known to the French?

BW: Absolutely. In 2010 a voluminous biography of Stein appeared in French by Nadine Satiat, and there are many French people who love to read Gertrude Stein either in translation or in the original. The major exhibit of the Stein family art collection that toured the United States in 2012 had a highly successful tournée at the Grand Palais in Paris. Surprisingly, though, few French people know about Stein’s feelings toward the Vichy regime.

AWP: Could you talk about your process as a writer?

BW: I write very slowly, with exhaustive attention to rhythm and cadence; and I revise constantly. It took me ten years to write this book. I always tell my students that writing is the hardest thing I do by any measure.

AWP: Do you keep a journal?

BW: I keep starting and stopping journals. A month ago I diligently started a journal that ended up becoming a scrapbook for my son to jot down football plays. I thoroughly believe in keeping a journal, but I just can’t manage to stick to it.

AWP: You are a professor of English at Dartmouth College. How did your interest in gender and culture studies unfold?

BW: I had a feminist mother, and a father who was a poet; there was never any question that I would end up being interested in gender and literature!

AWP: Your work has won great recognition. How has this experience changed your world?

BW: Thank you for that. I’m not sure about “great recognition,” but it has been exciting to hear people respond to my work, even in critical ways. I want to feel like my work has contributed to an important discussion.

ART OF LIVING

AWP: Name the single book, movie, work of art or music, fashion or cuisine that has inspired you.

BW: I am constantly inspired by fashion, and by silhouettes I glimpse on the street. Right now I am in love with the look of my close Parisian friend Mira, who has cropped her hair short and dyed it a very chic shade of dark purple. Gorgeous!

AWP: What is the last book you read? Would you recommend it?

BW: The last book I read was called The Melancholy of Resistance by Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai. It is one of the subtlest books I have ever read. And hilarious.

AWP: Your life is extraordinary. What’s next?

BW: Teaching, traveling, lecturing—and settling down at my desk to write about the extraordinary Samuel Beckett!

Books, on women and France, recommended by Barbara Will

Carole Maso, The American Woman in the Chinese Hat. Set in Arles and on the cote d’Azur, this somewhat experimental but romantic and wrenching novel tells the story of a doomed woman’s passion for life and all that France seems to offer.

Patrick Modiano, Dora Bruder. Although I would recommend all his books, this is my favorite novel by this major writer. The story of young Dora’s experience in Paris during the dark years of the Vichy regime is utterly haunting. A deeply ethical book as well.

Edna O’Brien, August is a Wicked Month. I read this short novel when I was in my 20s, living in the south of France (where the novel is set), and it was the perfect blend of sex, wit, and dark romance.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post, French Impressions: Alan Davidge leading visitors in the footsteps of the soldiers who liberated Normandy the summer of 1944. D-Day historian from Normandy, Alan Davidge, writes about personalized tours that have been particularly successful and moving for young people for whom the concept of war is often difficult to grasp. His success is due to his treatment of the subject as social rather than military history, looking at how the war affected ordinary men, women, and families.

Normandy never forgets: WWII monuments and memorials in France (part one), by Alan Davidge, D-Day historian for tours in Normandy. Alan shares a number of places of significance and remembrance. Guides included. (Part two)

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2014 Barbara Will. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com