Stars, Stripes, and Seine: Americans in occupied Paris 1940-1944

16 Tuesday Apr 2013

A Woman’s Paris™ in Cultures

Tags

African Americans, African Americans Paris, Alice B. Toklas, Alice-Leone Moats, American D Day, American women in Paris, Americans in Paris in 1920s 1930s, Americans in Paris Life and Death under Nazi Occupation 1940-44, Arthur Briggs, August 1944 Paris France, Bohemians in Paris, Bois de Boulogne, Champs-Élysées, Charles Bedaux, Clara Longworth de Chambrun, Combined Works of Shakespeare, Danse Sauvage, Dr Sumner Jackson, Drue Leyton, Edward and Mrs Simpson, Ernest Hemingway, France, General de Gaulle, Général Leclerc 2nd Armoured Division, Gertrude Stein, Jacques Tartière, James Joyce, Josephine Baker, Liberation of Paris, New York Herald Tribune, Paris, Paris expatriates, Pearl Harbour, Pierre Laval, Ravensbuck Neuengamme, Résistance France, rite de passage, Roosevelts, Shakespeare and Company Paris, Sylvia Beach, TS Eliot, US 4th Infantry Division Paris 1944, Von Choltitz, Walt Whitman, Wehrmacht, Wiliam Bullitt Mayor of Paris

Share it

By Alan Davidge

5,000 Americans refused to leave Paris after war broke out in September 1939. Who were they? Why was Paris a magnet for such a diversity of Americans in the 1920s and 30s? Inter-war America had become quite repressive for many people. Bohemians, people of color, individuals with strong political views, members of the GLBT community, artists and writers found Paris much more tolerant. Read the stories of how Josephine Baker, Sylvia Beach, Arthur Briggs, Drue Leyton, and others lived and breathed Paris during the war.

Stars, Stripes and Seine: Americans in occupied Paris 1940-1944

One of the most memorable images associated with the re-occupation of Paris at the end of August 1944 is that of General de Gaulle marching down the Champs Elysées, surrounded by cheering Parisians and visually neutralising the infamous propaganda pictures of Hitler and his henchmen striding along the same route four years earlier. Beside de Gaulle and his men we see images of the tanks of Général Leclerc’s 2nd Armoured Division and soldiers of the US 4th Infantry Division who made the first inroads into the city.

These newsreels were broadcast worldwide, including in the United States, and I wonder how many Americans watching at home realized that many of their fellow countrymen and women had also endured l’occupation alongside native Parisians.

Inter-war America had become quite repressive for many people. Bohemians, people of color, individuals with strong political views, members of the GLBT community, artists, writers and anyone who liked a drink or two found Paris much more tolerant. One another side of society were those who, like Walt Whitman, regarded a stint in France’s capital as an important rite de passage.

German troops arrived on June 14th 1940, two days after the departing French government had appointed the American ambassador William Bullitt as Mayor of Paris. His first act was to declare Paris an “Open City,” trading its right to resist in return for a peaceful occupation. Memories of the recent destruction of Warsaw by the occupiers were in everyone’s mind and Bullit’s quick action gave the city a fighting chance. Senior Nazi officers who occupied the city in subsequent months soon fell for its charms.

Hitler’s famous threat to leave the city in ruins if the Wehrmacht had to retreat never came to fruition when they were forced out after their four-year occupation, but the extent to which this was due owed to the cultural sensitivity of von Choltitz, who was given the orders to push the detonator buttons on the efforts of the Résistance, (many of whom had been assisted by Americans living in the city) is still a matter of debate.

Paris, an important rite de passage

Who, then, were these Americans who chose to remain in Paris alongside the German army of occupation, and whose side were they on, if any? It has been estimated that contrary to the Ambassador’s advice, about 5,000 refused to leave the city after war broke out in September 1939 and at least half of these still remained after Paris was occupied. To understand their tenacity requires an understanding of why Paris was a magnet for such a huge cross-section of Americans in the 1920s and 30s.

Undoubtedly, many Americans who made Paris their home were from wealthy stock. The French-born but naturalized millionaire and close friend of Edward and Mrs. Simpson, Charles Bedaux, was happy to compromise in order to continue developing his business empire, and Clara Longworth de Chambrun, related to the Roosevelts, and Pierre Laval, the Prime Minister of the new Vichy government, appeared to accept the pro-Nazi regime but also worked hard to support the American Library, an essential lifeline to the American community.

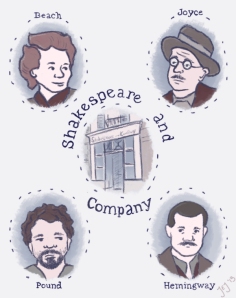

Sylvia Beach, whose bookshop Shakespeare and Company attracted the great American, British and Irish writers of the 20s and 30s, including James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway, continued to operate in defiance of German interference and also gave great support to all Parisians. The chief surgeon of The American Hospital, Dr. Sumner Jackson, took an even stronger line, and rather than concentrate on his own survival he worked with the resistance movements from day one, taking enormous risks in treating and repatriating allied servicemen.

African Americans, including the musicians who had found Paris so welcoming in the inter-war period, were sadly too conspicuous to escape the attentions of the Nazi regime. Hitler banned their concerts: they were ordered to report to the police and many were detained. The jazz trumpeter Arthur Briggs was sent to a concentration camp but he managed to keep his own flag flying by forming a classical orchestra with other black musicians. Josephine Baker, so famous for her topless Danse Sauvage in the 1920s, did manage to have the last laugh. She escaped internment, stayed at her country chateau, joined the Résistance, spied on the Germans and smuggled documents out of the country.

In the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941, American aliens in Paris held their breath and waited for something to hit the fan. They did not have to wait long. Within a week, all Americans in the “Occupied Zone,” which included the capital, were ordered to register with the nearest German Kommandant. What happened next depended partly on how German aliens were treated in the US, but the outcomes were not consistent for everyone. Over 300 men were arrested and interned after the registration deadline, but for favoured individuals such as Charles Bedaux it was simply a matter of house arrest. By January 1941 however, restrictions were starting to be relaxed. No women had been interned and some of the men were released and required to report weekly to their local police station. No Americans were interned in Vichy France as it was not at war with the United States.

American women in occupied Paris

The uneasy truce for American women lasted until September 1942 when they too became subjects for internment. Sylvia Beach barely had time to pack some winter clothes and a copy of her beloved Combined Works of Shakespeare before she was bundled into a truck headed for an internment camp at the zoo in the Bois de Boulogne. Here she met other Americans including a friend who was looking after the apartment of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas following their departure to the comparative safety of the Vichy Zone.

Also incarcerated in the Zoo was Drue Leyton, a famous American actress who had married a Frenchman, Jacques Tartière, and worked at the Paris Mondiale radio station before moving out of the city and commencing a long liaison with the Résistance. Before long, numbers were also swelled by groups of American nuns! In Sylvia’s account, she says that she also came across the wife of Charles Bedaux, eating a box of chocolates and anticipating imminent release because of her husband’s social connections, a prediction which soon materialized. Charles, her husband, was using his business and management skills (he is still considered to be one of the founders of modern scientific management techniques) to increase his wealth and influence at the expense of the Germans and worked closely with their intelligence service. He soon became an object of investigation of the FBI as a Nazi collaborator but was never fully trusted by the Vichy government or even the Germans themselves. His dangerous game eventually led to arrest and apparent suicide in February 1944.

Not long after their trip to the zoo, some of the women, including Sylvia and Drue Tartière were transported to Vittel, a spa town in the far east of France, to be kept in the relative comfort of a hotel. They enjoyed better conditions than the English women who were also interned there, which inevitably led to some internal frictions. Fortunately for Drue, she was allowed back to Paris by the end of the year but Sylvia had to endure Christmas in confinement, despite her friends lobbying the Nazis to release her. Eventually, by March 1943 she found herself on the way home. Once in Paris, she met up with Drue again and worked with her and her Résistance colleagues in repatriating Allied airmen.

The American Hospital in Paris

Dr. Sumner and his family had been engaged in similar activities at the American hospital and in the summer of 1943 took an even greater risk by responding to a request from the Résistance to allow their son Phillip, aged 15 and less likely to appear suspicious, to travel to the port of St. Nazaire and photograph German submarines. This mission was completed successfully and the film dispatched to very grateful contacts in London.

By 1944 the Jacksons were under increasing pressure, poorly fed and in such bad health that Dr. Sumner Jackson contracted pneumonia. They battled on, processing even more British and American airmen until, on 25 May, less than two weeks from D-Day which would signal the beginning of the end of German occupation, they were arrested by the Vichy government’s secret police, the Milice or “French Gestapo.” The family was separated, questioned and taken to several destinations that made it impossible for friends and colleagues to track them down. Mrs. Jackson was taken to Ravensbruck where she remained until the end of the war while father and son were sent to the infamous Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg where they remained until the approach of the British army at the end of April 1945. At this point prisoners were quickly bundled into ships with German troops which took to sea in an effort to escape, but they were promptly bombed by the RAF. One of the few survivors was their son Philip, but Dr. Sumner Jackson, who had saved the lives of so many allied airmen was never seen again. Ironically his death took place three days after Hitler’s suicide.

The Liberation of Paris

By April 1944 the American women who had chosen to tough it out in Paris were joined by a compatriot, Alice-Leone Moats, the Madrid correspondent of the New York Herald Tribune, who was determined to enter Paris and get reports back to the United States. Her journey via the Pyrenees was a remarkable one, as every day she risked being captured and shot as a spy, but the Résistance guided her through to Paris. She conducted some amazing interviews and eventually returned to Madrid to complete the first report by a journalist from Paris in well over two years, but it was censored by the Spanish for fear of German reprisals. Eventually it was filed from Portugal and she returned to New York.

After troops landed in Normandy on D-Day, 6 June 1944, it was simply a matter of time before Paris would be liberated. With this in mind, Hitler hatched a plan to ensure that the retreating army would leave it in ruins. Thanks to the delaying tactics of von Choltitz, the German officer in charge and the cunning of the Résistance, this never took place, but during those last few days before the arrival of General Leclerc’s 2nd Armoured Division and the US 4th Infantry, the city was a war zone for aliens and Parisians alike. The American hospital in particular was caught in the thick of it.

Immediately after the Libération, the former American ambassador, William Bullitt returned to his old embassy as the city and its people tried to return to some kind of normality. The American hospital continued to function but Sylvia Beach never re-opened her bookshop, although she continued to receive famous authors such as TS Eliot as her guests. She did, however, become more involved with the American library and donated many of her books. Clara de Chambrun and her husband, who had done so much to keep the library running, were eventually excluded from their role because of their connection with the Vichy government.

Paris, a new home

If the clouds of war have a silver lining, it is the way in which depredation and danger can bring out the best in people. Many of those who had chosen Paris as their new home were not prepared to forsake it, or their new family of friends, in its hour of need. Whether it was the daily heroics of those who were supporting the Résistance and saving the lives of downed airmen or the simple bloody-mindedness of those who would rather cross the street than share the pavement with an invading army, it is to be applauded and honoured.

I would not have been aware of these remarkable people if I had not come across Charles Glass’ comprehensive work: Americans in Paris: Life and Death under Nazi Occupation 1940-44 in a bookshop on a recent visit to England. It’s a compulsive read and as soon as you finish, I guarantee you’ll be on the internet to research the key characters further.

Alan Davidge was born in London two years after World War Two ended. Now after forty years of working in education, he lives with his wife, Carol in a part of Normandy that was liberated by US troops who landed on D-Day. They have recently moved out of the Norman farmhouse that took five years to renovate and are now taking on the bigger challenge of restoring an old cottage that carries a 1785 datestone above the door and sits in an acre of land. Since 2009, Alan has been using his knowledge and experience as a historian to accompany visitors around the Normandy beaches and battlefields. His email contact is: alandavidge10647@yahoo.co.uk

Alan Davidge was born in London two years after World War Two ended. Now after forty years of working in education, he lives with his wife, Carol in a part of Normandy that was liberated by US troops who landed on D-Day. They have recently moved out of the Norman farmhouse that took five years to renovate and are now taking on the bigger challenge of restoring an old cottage that carries a 1785 datestone above the door and sits in an acre of land. Since 2009, Alan has been using his knowledge and experience as a historian to accompany visitors around the Normandy beaches and battlefields. His email contact is: alandavidge10647@yahoo.co.uk

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post, Normandy never forgets: WWII monuments and memorials in France (part one), by Alan Davidge, D-Day historian for tours in Normandy. Alan shares a number of places of significance and remembrance. Guides included.

Normandy never forgets: WWII, a homecoming (part two), by Alan Davidge, D-Day historian for tours in Normandy. Alan shares his remembrance of a tour he created for an American WWII veteran who was returning with his daughter to visit places in France where he had served.

D-Day Travel Guide: For American visitors to Normandy, France, by Alan Davidge, D-Day tours historian, Normandy. Alan has managed to seek out a number of places of significance that do not usually feature in guidebooks. Guides included.

French Impressions: Kristin Adele Graves and her fascination with heroine Josephine Baker. Kristin Adele Graves, doctoral candidate in African American Studies and French at Yale University, writes about Josephine Baker, a woman who did it all—singer, dancer, film and theater actress, political activist, and author. Baker rose to unprecedented and unparalleled success in the 1930s.

French Impressions: Catherine Watson on literary travel writing and memoir. Award-winning author, travel writer and photographer, Catherine Watson has developed a career that has taken her around the world three times, to all seven continents and into 115 countries. Catherine shares her life, on and off assignment, as a solo traveler.

Text copyright ©2012 Alan Davidge. All rights reserved.

Illustration copyright ©2012 Jenny Jorns. All rights reserved.

Illustration copyright ©2012 Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com