The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944 – Excerpt from Ronald C. Rosbottom’s “When Paris Went Dark” (Part One)

22 Friday Aug 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Cultures

Tags

Albert Camus, City of Light 1940-944, Colette, Jean-Paul Sarte, Joseph J Ellis Ford Foundation Professor Emeritus Mount Holyoke College, Joseph J Ellis Founding Brothers American Sphinx and Revolutionary Summer, Josephine Baker, Liberation of Paris 1944, Marechal Philippe Petain, Pablo Picasso, Paris under German occupation 1940-1944, Ronald C Rosbottom Amherst College faculty, Ronald C Rosbottom Amherst Massachusetts, Ronald C Rosbottom Romance Languages Department Ohio State University, Ronald C Rosbottom University of Pennsylvania, Ronald C Rosbottom Winifred Arms Professor in the Arts and Humanities professor of French and European Studies Amherst College, Scott Turow Identical, Simone de Beauvoir, Third Reich Paris occupation, When Paris Went Dark Ronald C Rosbottom Little Brown and Company

Share it

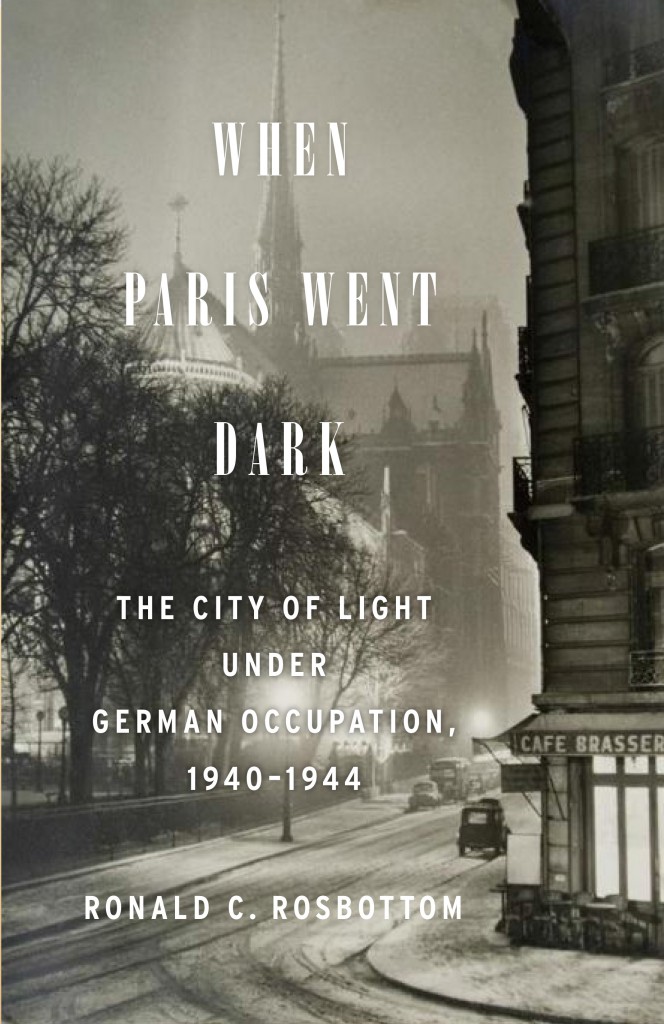

Excerpted from the book When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944, by Ronald C. Rosbottom. Copyright © 2014 by Ronald Rosbottom. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company.

Excerpted from the book When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944, by Ronald C. Rosbottom. Copyright © 2014 by Ronald Rosbottom. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company.

June 14, 1940, German tanks entered a silent and deserted Paris and The City of Light was occupied by the Third Reich for the next four years. Rosbottom illuminated the unforgettable history of both the important and minor challenges of day-to-day life under Nazi occupation, and of the myriad forms of resistance that took shape during that period. Slowly, as the Occupation became increasingly onerous, underground resistance efforts became more and more muscular. Groups and individuals of all stripes—French and immigrant Jews, adolescents, communists, Gaullists, police officers, teachers, concierges, and landlords—endeavored to remind the German authorities that Parisians would never accept their presence. Cultural icons such as Josephine Baker, Picasso, Sartre, de Beauvoir, Colette, and Camus developed their own strategies to resist being overpowered by an invidious ideology.

This August marks the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris, perfect timing for Ronald C. Rosbottom’s riveting history of the period: When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation 1940–1944 (August, 2014; Little, Brown and Company). (Purchase)

Chapter One: A Nation Disintegrates (Part One)(Part Two)

It is with anguish that I tell you that we must lay down our arms. — Maréchal Philippe Pétain1

Preludes

How did this debacle happen, and so rapidly?

When Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, feverish diplomatic efforts were engaged to obviate the treaty obligations that would force Britain and France to come to her defense. After declaring war on Germany a few days later, both nations almost desultorily began preparations for a European war. The French had increased their already large army to about 2.5 million men. They pushed past their own Maginot Line in eastern France and moved cautiously a few kilometers into Germany, where they met little resistance, for the Luftwaffe and the panzers of the Wehrmacht were firmly engaged in Poland.* Thus began nine months of the “phony war” on the Western Front, as Hitler bided his time before taking on the combined Allied forces of Holland, Belgium, France, and the United Kingdom. One of the lasting effects of Poland’s treaty partners’ lack of resolve to help the country more aggressively — except for a few naval and land sorties by the French and British, Poland fought Germany alone during that deadly month — was not only a wariness on the part of other Allied nations toward the “big two” but also an internecine distrust between France and Great Britain themselves. Nevertheless, there was a general confidence, born of years of propaganda, that France’s army — believed to be the greatest fighting force in Europe, if not the world — was invincible and that England’s navy only increased that invulnerability. It was widely argued that the Germans would be embarrassingly battered should they try to invade any nation other than Poland, which, after all, had been fought over for centuries, its boundaries changing with the vagaries of the political strength of its most powerful neighbors, Germany and Russia (later the USSR).

* The Maginot Line was an extensive series of massive forts built into the terrain in the 1930s from the border of Switzerland to Luxembourg. This was France’s first line of defense against a German invasion. The Germans, of course, went around it in 1940.

Still, Paris was nervous. A national mobilization was imposed, and recruits from all over the nation were arriving at train stations and leaving hourly for the Maginot Line and other fronts. The government was introducing the public to “passive defense” training — that is, showing them what to do in case of an air raid. Blackouts, air raid sirens, and other interruptions of daily life became de rigueur. Métro stations were turned into shelters, and almost every apartment house had an abri (shelter; the word can still be seen painted in the basements of many Parisian buildings). Dozens of concrete blockhouses were hastily constructed on the major roads leading into Paris. But these were offhand, almost casual attempts at forestalling an invasion that no one believed would really happen. France was just too strong. But within barely six weeks, the German juggernaut would have breached Paris’s gates, and a quickly agreed‑to armistice was signed.

Many saw the armistice that Maréchal Philippe Pétain, newly named head of government, had confirmed with the Germans as a respite, necessary for France to get its household in order while the Germans pushed their war against England. The decision to call for an armistice was not welcomed by everyone, but most French were confident that this political arrangement with Germany would be necessary for only a limited period. Parisians in particular had been through a rough patch of political disagreement during the 1930s, including bloody street confrontations. At least a dozen French governments had been installed and dissolved since Hitler’s ascension to the Reich’s chancellorship in 1933. For many French, the example of a stable Third Reich seemed to promise the sort of national pride and civic predictability found lacking on their side of the Rhine. In 1939, the Third Republic, established in 1871 after the civil war that had followed France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, was at the nadir of its popularity. The Armistice would allow a harried nation to catch its breath.

But many on the left in 1940 suspected that the Armistice was the French right’s revenge — a way to undermine the legacy of the Third Republic, which they despised. Since the Dreyfus affair (1894–1906), when a Jewish army officer was framed for distributing illicit intelligence to the Prussians, the political right, composed essentially of the military, the very Catholic, the aristocratic class, monarchists, and industrialists, had seen or imagined their power wane. The emphases of the Third Republic on public education, support of labor, secularism, and a social safety net appeared to them to have doomed the nation to mediocrity. In addition, once European fascist savagery erupted, France had welcomed tens of thousands of immigrants from Spain (Republicans fleeing Franco) and from Germany and eastern Europe (Jews and other political dissidents). Their presence infuriated the right, enhancing French nativism. A new government, this time headed by a respected military leader, could put the nation back on a more conservative track.

One of those who most fretted during this confusing period was the thirty-one-year-old Simone de Beauvoir, a brilliant schoolteacher and writer then unknown to the French public. (She would not publish her first work, a novel — L’Invitée [She Came to Stay] — until 1943.) A confidanteand lover to Jean-Paul Sartre, the existentialist philosopher who had gone off to war in 1939, de Beauvoir has left us detailed descriptions of her reactions to the way confused Parisians, especially intellectuals, schoolteachers, writers, and artists, felt as they saw their city invaded by the minions of a gang of thugs. Assigned to meteorological duties near Nancy, in the eastern part of France, Sartre himself would be taken prisoner when the Germans finally invaded. He was then shipped off to a German prisoner of war camp (from which he would be released in April 1941). De Beauvoir worried about Sartre, though she regularly received letters from him, at least during the so‑called phony war (the French called it drôle de guerre) — the period between September of 1939 and May of 1940, when the only major battles in Europe were the Polish campaign and the Russo-Finnish (“Winter”) War.

De Beauvoir noticed almost immediately a change in Parisian temperament as its citizens awaited with anxiety, but not yet dread, the results of their mutual defense pact with Poland. In the diary that she kept during these lonely months, she noted that there was a “mini exodus” out of Paris — nothing like the one that would empty the city nine months later, but still a symptom of Parisians’ bafflement at the threats from new types of warfare. As she accompanied Sartre to his mobilization reporting station in late 1939, she noticed that

Passy [part of the fashionable 16th arrondissement] was completely deserted. All the homes were closed up and not a single soul in the street, but an unending line of cars passing on the quay, crammed with suitcases and sometimes with kids. . . . [Later] we walked up Rue de Rennes. The church tower of St. Germain-des-Prés was bathed in beautiful moonlight and could be mistaken for that of a country church. And underlying everything, before me, an incomprehensible horror. It is impossible to foresee anything, imagine anything, or touch anything. In any case, it’s better not to try. I felt frozen and strained inside, strained in order to preserve a void — and an impression of fragility. Just one false move and it could turn suddenly into intolerable suffering. On Rue de Rennes, for a moment, I felt I was dissolving into little pieces.2

This feeling of anxiety and of alienation from her familiar environment, of a “narrowing” of her sentient world, would soon spread to all Parisians, before and during the Occupation itself. With these sentiments came another that de Beauvoir was especially attuned to: the fact that anticipation of war, military occupation, and resistance called for a recalibration of psychological as well as physical senses of time. She said often in her diary that she felt “out of time”; that she desperately wanted to know the future and not be seduced by past happier memories, and that she wanted to mitigate her impatience at having constantly to live in the present. “Boredom,” she wrote on September 5, “hasn’t set in yet but is looming on the horizon.”3 By November, she was writing: “For the last two months I had lived my life simultaneously in the infinite and in the moment. I had to fill the time minute‑by‑minute, or long hours at a time, but entirely without a tomorrow. I had reached the point that even the news of military leaves, which gave me hope by defining a future-with-hope, had no effect on me and [was] even painful to me, or almost.”4

Another prescient chronicler, Edith Thomas, an active French Communist and archivist, kept a daily journal of the Occupation that came to light only in the early 1990s.* Thomas described what Paris was like on May 8, 1940, only two days before the Blitzkrieg would end and the taking of Paris would begin:

The desert of the streets, and the dead squares at night. Paris [after the grand exodus] is like . . . a city become too large for those who live there. They walk along under the funereal streetlights covered in blue paper, which give no more light than the candlelight of my childhood. Steps sound as if they are coming from empty rooms where it seems that no one will ever live again. Everything is too big; frightening, bluish, dark, and the shadows of men are lost as if they were in the deepest of forests.5

* The French Communist Party was the best-organized political group on the political left. Its support of the leftist Front populaire government in 1936–37 and again in 1938, and of the Spanish Republic during that country’s civil war (1936–39), had given it much moral authority as an antagonist of fascism. Its membership growing in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Party had been hog-tied by Hitler’s cynical 1939 nonaggression pact with Stalin, signed just weeks before the invasion of Poland. Nevertheless, it continued to organize. The largest anti-fascist organization in France, it was also the most feared by the new, collaborationist Vichy government.

We know how things would end, but back then Parisians had no concrete information, so rumor, guessing games, BBC propaganda, and news bulletins took the place of planning. This waiting was one of the most enervating aspects of the Paris during the war, especially after the Germans arrived. It would not end until Allied tanks were seen on the outskirts of Paris in late August of 1944.

Praise for When Paris Went Dark

“A riveting account of one of the most resonant hostage takings in history: the 1,500 days when a swastika flew from the Eiffel Tower. Ronald Rosbottom illuminates every corner of a darkened, heartsick city, exploring the oddities, capturing the grisly humor, and weighing the prices of resistance, accommodation, collaboration. The result is an intimate, sweeping narrative, astute in its insight and chilling in its rich detail.” —Stacy Schiff, author of Cleopatra, A Great Improvisation, and Véra

“When Paris Went Dark recounts, through countless compelling stories, how Nazi occupation drained the light from Paris and how many of its residents resisted in ways large and small. This is a rich work of history, a brilliant recounting of how hope can still flourish in the rituals of daily life.” —Scott Turow, author of Identical

Ronald C. Rosbottom is the Winifred Arms Professor in the Arts and Humanities and a professor of French and European Studies at Amherst College. Previously he was the dean of the faculty at Amherst and the chair of the Romance Languages Department at Ohio State University. He lives in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Ronald C. Rosbottom is the Winifred Arms Professor in the Arts and Humanities and a professor of French and European Studies at Amherst College. Previously he was the dean of the faculty at Amherst and the chair of the Romance Languages Department at Ohio State University. He lives in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Photo credit: Kane Haffey

A Woman’s Paris® is a community-based online media service, bringing fresh thinking about people and ideas that shape our world and presents a simplicity and style, in English and French.

Connecting with you has been a joyous experience—especially in learning how to enjoy the good things in life. Like us on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter. Share us with your friends.

Barbara Redmond

Publisher

barbara@awomansparis.com

Text copyright ©2014 Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group, Inc. © 2014 Ronald C. Rosbottom. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com