Susan Winkler’s “Portrait of a Woman in White” – a story of love and loss (excerpt)

18 Tuesday Nov 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Cultures

Tags

Belle Époque France 1940, Douglas Preston White Fire, Dr David Altshuler, France, Henri Matisse, Hermann Göring, Museum of Jewish Heritage, Paris, Paris at the End of the World John Baxter, Portrait of a Woman in White Susan Winkler She Writes Press, Rose Valland, She Writes Press, Susan Winkler, The Hotel on Place Vendome Tilar J Mazzeo HarperCollins, When Paris Went Dark Ronald C Rosbottom

Share it

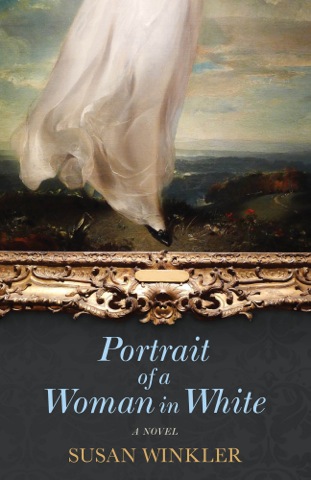

Excerpted from Portrait of a Woman in White: A Novel by Susan Winkler. Copyright © 2014 by Susan Winkler. Used with permission of She Writes Press. All rights reserved.

Excerpted from Portrait of a Woman in White: A Novel by Susan Winkler. Copyright © 2014 by Susan Winkler. Used with permission of She Writes Press. All rights reserved.

Portrait of a Woman in White is an engaging exploration of love and loss. The eccentric Rosenswig-Assouline family is immersed in a belle-époque lifestyle filled with art and antiques in their splendid chateau, Le Paradis. The Matisse portrait of Lili’s mother hangs in their Paris salon. The day before ardent young lovers Lili and Paul plan to marry, the Nazis invade Paris, and they are irrevocably thrust into the pressure cooker of war. The family flees toward Lisbon, but at the border Paul is detained and compelled to join the French army, while Lili is forced ahead to America. As their fortunes fall, Lili and Paul and the others scramble to do what they must to survive while trying to adapt to the emotional devastation. When the beloved Matisse portrait is looted by Nazi leader Hermann Göring, their fate is ultimately interwoven with that of their portrait. This is their search for lost love and lost art, set to romance and mystery, inspired by history.

The search for lost family, lost love and lost art was inspired by the author’s family history, and while the Rosenswig family is fictitious, other key players and events include the historic, from Henri Matisse and Hermann Göring to French museum spy Rose Valland. A terrific historical novel suitable for bookclubs with live author conferencing. To purchase Portrait of a Woman in White: A Novel (September 2014, She Writes Press), visit: Portrait of a Woman in White.

Subscribers, Portrait of a Woman in White by Susan Winkler, journalist and author, gives us a novel of an eccentric family immersed in a belle-époque lifestyle and a Matisse portrait that hangs in their Paris salon. Free book giveaway to two subscribers ends November 21, 2014. A $16.95 U.S. value (September 2014; She Writes Press).

Subscribe free. Once subscribed, you will be eligible to win—no matter where you live worldwide—no matter how long you’ve been a subscriber. You can unsubscribe at anytime. We never sell or share member information.

Praise for Portrait of a Woman in White

“Fiction depicting one family…serves deep truths about individuals and societies. We are invited to consider how art is valued or debased, and what is transitory in our lives, what permanent. A compelling journey.” —Dr. David Altshuler, Founding Director, Museum of Jewish Heritage

“I’ve read Portrait with great enjoyment. What a beautiful story.” —Douglas Preston, New York Times bestselling author of White Fire.

Visit: French Impressions: Susan Winkler’s “Portrait of a Woman in White” on love, loss, and the human ability to reinvent oneself, her interview on A Woman’s Paris®.

Portrait of a Woman in White: June 1940 (chapter one)

Tomorrow was to have been her wedding day.

They allowed themselves just the few hours before nightfall to pack—a single suitcase for each of them, and only what they could easily carry. Alone in the waning light of the bedroom, Lili stopped to examine the small heap on her bed: extra socks, a warm jacket, a bar of scented soap, a hairbrush. How could this insignificant pile sustain her? She added all of it to the belongings in the worn leather valise and pushed down hard to make more space. Then she turned to the bedside table, where a clock stood alongside a family photograph and two blue sketchbooks lay open next to an empty box of artists’ pastels. The radiant colors spread across the table in luxurious disarray. In an anguished motion, she gathered up the pastels and placed them back into their dark wooden box and closed the sketchbooks. She arranged these final items carefully on top of the pile, lowered the lid of the valise over everything, and, with a final, devastating snap, shut the bag. Her dreams went dark.

The Nazis had stormed into France and were sweeping toward them. Tomorrow she would have married Paul. These were the facts, simultaneous and irrevocable. Yet when she tried to comprehend them, she was overwhelmed by a longing for all that had gone before and all that was to have been.

Where was Paul? As strong as she had been during the hour before, she needed him with her now. Outside, she saw that the sky had grown black, and a wave of exhaustion passed through her. Shivering, she curled her body onto the small bed. She could shut her eyes for a few minutes, at least.

With an explosive boom, her uncle’s voice reverberated from down the hallway. “No! We cannot risk complications with jewelries. You must choose from your favorites, not everything.” Aunt Jeanne’s reply was unintelligible. Lili had visions of her frantically attempting to sew her beautiful ruby-and-diamond rivière necklaces into her hemline, dragging it down ridiculously.

From another room, her father insisted that he must bring his radio. “But Maurice, it’s too big, and anyway, we can’t count on electricity,” her mother tried to reason with him.

“Then how will I know what’s going on?” he shouted back in bewilderment. Lili shut her eyes in an effort to escape this growing nightmare.

When she opened them again, it was dark and quiet. She sensed Paul’s nearness in the shadows by the bed. When he leaned over her to stroke her cheek, she could make out the long outline of his body, so close now that she thought she could hear his heartbeat.

“Lili, it’s almost time to leave,” he whispered. His warm breath moved across her forehead. “We have no choice. But I hate the idea of it.”

“I know. So do I,” she said, her voice quavering. He touched her lips lightly, as if to silence them. There was so much to say, but neither dared speak about what might go wrong; there were far too many ugly possibilities.

Paul reached out to switch on the table lamp and sat down next to her on the bed. In the soft light, she could see the tenderness in his hazel eyes, their golds and greens.

“Do you remember when we played here as children?” She took his hands and cradled them to her cheek. “Once, you found me fainted on the floor, and when you lifted my hand to check my pulse, I felt comfort in your touch. Now they are the healing hands of a doctor. I want your hands with me, always.”

Drawing her to him, he held her and stroked her hair. “In my mind, Lili, you are already my wife. Soon, I promise you, we will stand side by side under the wedding canopy. I will crush the wineglass and gaze into your eyes before we kiss, and we will be one. Our future will be together.” When he put it like that, with such certainty, she believed him.

It was time. The family was gathering in the marble foyer with their packed belongings. Lili could not leave without first taking in every detail of the rosy-hued bedroom. On the nightstand she’d placed a photograph to remind her of their life in Paris—had it been only twelve weeks earlier that they’d fled the city for the safety of the countryside? Nowhere was safe anymore.

Lili picked up the photograph. It had been taken on the happiest of days, when they were gathered together on her mother’s birthday to celebrate the portrait Matisse had painted. Sonia Rosenswig smiled serenely from the red velvet chair, almost a mirror image of the elegant portrait newly hung on the wall beside her. In the photograph, as in the portrait, Sonia wore a white dress, and the emerald ring was on her finger. Maurice stood proudly behind her, his hands resting gently on the back of her chair; Henri was to her left and Lili to her right. Jeanne and Eli Assouline stood next to Maurice, and behind Lili stood Paul Assouline, his fingers touching Lili’s in the hidden folds of her skirt.

Life had seemed perfect to her then. She’d had a sense that they would look back on this as the golden age of the family Rosenswig. Impulsively, she slipped the photograph into the pocket of the sweater she wore over her dress.

That night the family drove off the property in silence. An Oriental rug had been thrown down over the enclosed flatbed of the borrowed truck, where Lili squeezed in next to Paul, their extended legs touching, hemmed in by luggage and a well-stocked picnic basket. Henri drove, with Maurice and Sonia on the banquette next to him and Eli and Jeanne seated right behind, along with more suitcases. The nighttime temperature was cool; Lili kept her right hand interlocked with Paul’s and the other inside the pocket that held the photograph.

It was a long ride to the Spanish border, and beyond that, Lili couldn’t bear to contemplate. The main roads were already crowded with refugees, some on foot, some with livestock or carts, and a few others lucky enough to travel in cars or trucks. France was in a political twilight; Paris had fallen, but French soldiers in the provinces were preparing for battle. No one knew how long they would fight or if there would be an armistice. To the Rosenswigs and Assoulines, it hardly made a difference. No matter how profoundly they thought of themselves as French, they were Jews.

Dawn had not fully broken when they arrived; Lili squinted to survey the surrounding scene. “So, we’re not the first in line after all,” Henri announced, shutting down the truck’s motor on the small patch of brown grass he’d staked out for them. Awake and bleary eyed, the family members registered their situation one by one.

With the Germans marching relentlessly toward the border, they’d hoped to be whisked through to Spain a few steps ahead of the troops. Apparently, so had everyone else here at France’s final outpost.

“My God! I don’t know where I’ve ever seen so many French. It’s like a political rally in Paris. Do you suppose the entire government is leaving, too?” said Maurice, attempting to cover his surprise with sarcasm

“Look, there. It must be Spain.” Sonia pointed ahead, ignoring him.

“Yes, we can almost touch it from here,” Jeanne agreed enthusiastically. Sighing, she rested a manicured hand on her breast as though their ordeal were finally over, then took a moment to arrange the waves in her hair.

“But not quite. Believe me, my dear, it looks much closer than it really is,” Eli said. In his accented voice, rich and melodious through his mustache, it sounded like a warning, as though he were privy to some secret information.

Lili pushed aside the curtains to peer through the dust-covered window, trying to make out the extent of the confusion around them. She had not prepared herself for what she saw: a procession of wagons and bicycles, horses and oxcarts, all carrying children, parents, and grandparents. Some were in cars. Still others walked, or hobbled with fatigue.

“They can’t all be going with us to Lisbon,” she gasped.

“Yes, I’m afraid we’re all clamoring all for the same thing, to leave France, to cross Spain, to enter Portugal, to make it to Lisbon and onto a boat bound for far away,” Paul said quietly.

She thought back to the darker, broader threat in Eli’s remark and whispered, “Your father is right. Everything looks closer and appears easier because we are desperate.”

It seemed obvious that they were doomed to tire of the confines of the hot, stuffy truck and would inevitably join the hundreds of other refugees who paced the camp anxiously. But for how long? Certainly everyone hoped to be let through first, and surely there were those who felt they deserved to cross before the others. In the end, they would discover that they must wait, and wait, and wait, together—first for their turn to pass inspection by the officious French police, then for inspection by the Spanish, who took their time to open every single bag.

Hours passed slowly in the camp, overcrowded with hungry and cranky, dirty and exhausted bodies, engaged mostly in complaining and bickering. “Where did it go, the civilized behavior that we French pride ourselves on?” Lili wondered aloud.

“Let’s get out and look around,” suggested Paul. It was the only thing to do.

Henri had used his extensive contacts to obtain for the Rosenswigs and their Assouline relatives the Portuguese transit visas that were required to enter Spain. The Rosenswigs were called up first. It was early the next morning, when the camp was still enveloped in fog. They were to pass French inspection at the guard booth, then cross the wooden footbridge into Spain. Paul seemed to sense Lili’s nervousness and walked alongside her, carrying her bag.

Everything depends on this, she thought with each step. The knot in her stomach tightened. She could have run to the border, so anxious was she to reach safety. Eli’s voice replayed in her head: It seems much closer than it really is. She imagined the border receding to infinity, always a little farther, just beyond reach. As they neared the inspection area, she wanted to grab onto Paul and pull him through with her.

They walked past a small unit of French soldiers—one of them looked no older than sixteen. Paul remained next to her when the French border guard leaned his head out of his booth to glance at Henri’s paperwork.

He looked up sharply at Paul. “You! Are you a Rosenswig?”

“No, I am not. I’m only here to help my fiancée.” He held up Lili’s leather valise. “My name is Paul Assouline. I’m crossing with my parents, back there.” He put down the bag and gestured behind them.

There was a sudden commotion. Five of the young French soldiers burst forth to surround Paul, and in a swift, aggressive action they shoved him back to the refugee waiting area, out of Lili’s sight. Her face paled in alarm. Henri shot her a dark look, warning her not to protest.

“Sometimes they think they can sneak through like that, but we always catch them,” sniggered the guard, who had decided to examine the Rosenswig papers more closely. Lili held her breath as he took his time to finger through them, backward and forward, staring into the face of each Rosenswig.

When at last he was satisfied, he grunted and nodded that they could pass. Across the footbridge, the Spanish border patrol barely glanced at their visas.

Lili kept looking back, scanning the landscape for Paul. Something had detained the Assoulines on the French side. It was difficult to make out through the fog, but Eli appeared to be arguing with several of the soldiers and was pointing to the hem of Jeanne’s skirt, where her jewels were hidden. Eli threw his arms in the air, gesticulating wildly, but the soldiers ignored him, uninterested; they pressed Jeanne and Eli through to the next checkpoint.

Where is Paul? Lili looked miserably to her brother for an answer. Henri’s face was tense, but he only shrugged. Teetering between fear and nausea, she thought she might vomit.

From a distance, the Spanish border guards appeared to be interested in what Eli had offered, even if the French were not. Eli was on his knees at the Spanish checkpoint, tearing at the hem of his wife’s skirt and handing over the contents, her precious jewels. “Oh my God,” said Henri. “What gives them the right . . . ?”

At last Jeanne came over the bridge, squeezed between two soldiers who pushed her onward against her will. Tears streamed down her cheeks. She caught sight of Lili and called out breathlessly, “It’s Paul. They won’t let him pass! Those boys are drafting him into the French army. . . . He’s been conscripted to fight the Germans!”

Lili’s stomach plunged when she caught sight of Paul. She watched in disbelief as the French soldiers held him back, surrounding him, and pressed Eli through to Spain.

“No! Wait!” she shouted, so alarmingly loudly that they momentarily stopped short to look at her, waiting for an explanation.

In that instant she ran, right past the astonished Spanish police, across the footbridge, and back into France. She flew by the French border guards and stopped only when she reached the soldiers who guarded Paul, keeping him from her. Panting, she planted herself in front of them, stood tall, and took a deep breath.

“He must be allowed through!”

The soldiers had the insolence of youth. They leered at her and blocked her way to Paul. The youngest of them stepped right up to her, patted her cheek, and said with an arrogant grin, “Hey, your boy-friend’s going to help us fight the Germans. Don’t worry. With his help, we’ll win.”

“I’m a doctor. I could never fight,” Paul said, shaking his head, his eyes flashing.

“A doctor?” the soldier repeated snidely. “That’s even better. We’re short on doctors.” He positioned his bayonet in front of Paul, keeping Lili away. The border patrolmen who had watched Lili zoom past only a moment before caught up with her now. They were upset and yelling in Spanish and in French. They grabbed her by both elbows and started pulling her backward toward the bridge.

“No! No!” she screamed, trying to shake herself loose. But it was useless.

“Messieurs, that’s no way to treat a lady,” Paul upbraided them. They came to a stop. Then he held Lili’s frantic gaze in his steady one. Her hair had fallen loose from her chignon, and through the strands and welling tears, she watched his shoulders fall. He opened his mouth to speak. At first no words came out, but then he recovered and said to her confidently, directly, “Lili, it’s no use. Go back to your family. I will find you wherever you are. Don’t worry, I will find you.” Still, his words, his voice, did not achieve their usual calming effect.

“Wait! Let him take this . . . please.” She jerked an arm free and reached into her sweater pocket. The photograph taken on Sonia’s birthday was still there. She held it out toward Paul, silently beseeching him.

The youngest soldier grabbed it from her and studied it, before passing it on. “Here, Soldier—I mean, Doctor—your girlfriend’s in the picture. You’ll need it.”

Paul grasped the photograph without taking his eyes off Lili and slipped it inside his coat. He watched while they forced her back across the border into Spain. Her tears flowed uncontrollably.

“Survive, Paul. Survive and come back to me,” she prayed aloud.

I will find you wherever you are. Don’t worry, I will find you. Paul’s words echoed through her, imbuing her with his strength and faith.

“Yes,” she whispered, as though he could hear her. “We will find each other. The war will soon be over. I will write you from America. All of my life, you’ve been with me in my heart, and you are a part of me. If I lose you, I lose myself. A story that begins like ours can never end.”

Susan Winkler was born in Portland, Oregon and educated at Bennington College and Stanford University, L’Académie in Paris and the University of Geneva. She was trained as a journalist at Fairchild Publications in New York and had the enviable job of writing, and updating four editions of The Paris Shopping Companion: A personal Guide to Shopping in Paris for Every Pocketbook.

Susan Winkler was born in Portland, Oregon and educated at Bennington College and Stanford University, L’Académie in Paris and the University of Geneva. She was trained as a journalist at Fairchild Publications in New York and had the enviable job of writing, and updating four editions of The Paris Shopping Companion: A personal Guide to Shopping in Paris for Every Pocketbook.

Susan currently lives in Portland, Oregon and where she pursues a lifelong interest in art.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944 – Excerpt from Ronald C. Rosbottom’s “When Paris Went Dark” (Part One). June 14, 1940, German tanks entered a silent and deserted Paris and The City of Light was occupied by the Third Reich for the next four years. Rosbottom illuminates the unforgettable history of both the important and minor challenges of day-to-day life under Nazi occupation, and of the myriad forms of resistance that took shape during that period. August 2014 marks the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris, perfect timing for Ronald C. Rosbottom’s riveting history of the period.

Tilar J. Mazzeo’s “The Hotel on Place Vendôme” – Hôtel Ritz in Paris: June 1940 (excerpt). Tilar J. Mazzeo, author of the New York Times bestseller The Widow Clicquot, and The Secret of Chanel No. 5. This riveting account uncovers the remarkable experiences of those who lived in the hotel during the German occupation of Paris, revealing how what happened in the Ritz’s corridors, palatial suites, and basement kitchens shaped the fate of those who met there by chance or assignation, the future of France, and the course of history.

Proud, Sad and Angry: Normandy still stirs the emotions, by Alan Davidge. We can all be forgiven for thinking that history is all about dates and facts, although it is true that a day spent exploring the Normandy beaches will certainly add many of these to our memory banks. The real memories that we take away from Normandy, however, are the kind that go much deeper and touch parts of our soul, ensuring that we are never quite the same again.

John Baxter’s “Paris at the End of the World” – Patriotism transforming fashion (excerpt). Preeminent writer on Paris, John Baxter brilliantly brings to life one of the most dramatic and fascinating periods in the city’s history. Uncovering a thrilling chapter in Paris’ history, John Baxter’s revelatory new book, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, shows how this extraordinary period was essential in forging the spirit of the city we love today.

Anne Morgan’s war: American Women Rebuilding France, 1917-1924. Anne Morgan, daughter of the prominent financier J.Pierpont Morgan, and the 350 American Women—all volunteers—left comfortable lives in the United States to devote themselves to humanitarian aid in France; an account from the exhibition of photographs and silent films from the Franco-American Museum in Picardy, France. Château de Blérancourt, in Picardy, France was created by Anne Morgan and is today a national French museum devoted of friendship and collaboration between the United States and France.

Text copyright ©2014 Susan Winkler. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com