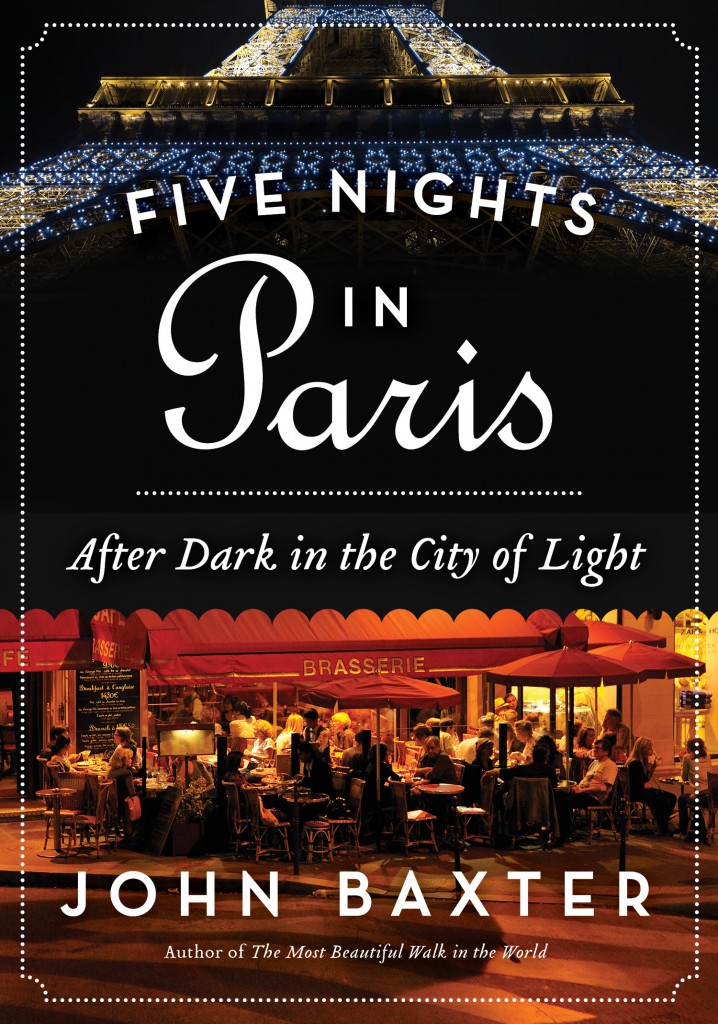

John Baxter’s “Five Nights in Paris” – a dazzling sensory tour of Paris’s greatest neighborhoods (excerpt)

14 Tuesday Apr 2015

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Travel

Tags

253 Books About France A Woman's Paris, A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict John Baxter, Alan Bennett, Alec Guinness, boulevard Saint-Germain, Boulevard Saint-Michel, Buttes Chaumont Paris, Champs-Élysées Paris, Chateau de Boussac France, Chronicles of Old Paris John Baxter, City of Light, Cluny Museum of the Middle Ages, Côte d'Azur, Deux Magots cafe Paris, Five Nights in Paris After Dark in the City of Light John Baxter Harpers Perennial, Fragonard perfumerie Grasse France, France, Fumée d'Opium Claude Farrère John Baxter translator, Georges Sand, Ile de la Cité Paris, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas John Baxter, Jacques Prévert poet, literary tours Paris, Louvre Museum Paris, Luxembourg Gardens Paris, Maria de Medici Musée de Luxembourg, Montmartre, Morphine Jean-Louis Dubut de la Forest John Baxter translator, My Lady Opium Claude Farrère John Baxter translator, Notre Dam Paris, Odéon Paris, Ottoman Empire, Paris, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War 1914-1918 John Baxter, Paris croissants, Paris monuments, Paris museums, Paris neighborhoods, Paris travel guide, Place Dauphine, Place Furstenberg, Pont Neuf Paris, Prosper Mérimée Bizet opera Carmen, rue Bonaparte, rue de l'Odéon Paris, rue Jacob, Sacré-Cœur Paris, Saint Sulpice Paris, Sylvia Beach Paris, Tapestries Cluny Museum, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s John Baxter, The Lady and the Unicorn Cluny Museum Paris, The Most Beautiful Walk in the World John Baxter, The Paris Men's Salon John Baxter, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France John Baxter, Vert Galant park paric, We'll Always Have Paris John Baxter

Share it

Excerpt from Five Nights in Paris: After Dark in the City of Light by John Baxter. © John Baxter. Reproduced by permission of Harper Perennial. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from Five Nights in Paris: After Dark in the City of Light by John Baxter. © John Baxter. Reproduced by permission of Harper Perennial. All rights reserved.

Any guidebook can tell you what to see and do in Paris during the day: Museums and monuments, cathedrals and croissants—the checklist of Parisian clichés is enough to keep any tourist busy until closing time. But what about when darkness falls on the City of Light? John Baxter wondered the same thing. Inspired by the literary tours he gave during the day, Baxter developed his dazzling sensory tour of Paris’s greatest neighborhoods.

Five Nights in Paris is enriched by anecdotes from Baxter’s own life in France and written with the alluring, authoritative voice only he can provide. From the late-night haunts of the city’s most storied artists and writers, to the scenes of its most infamous crimes, this unique travel memoir whisks its readers off to places you won’t find in your average guidebook.

For jetsetters and armchair travelers alike, Five Nights in Paris: After Dark in the City of Light is sure to become an instant classic and will make even the most dedicated home-bodies yearn for the land of cafés and literary greats. (April 14, 2015, Harper Perennial) (Purchase)

Free Subscription: Join our thousands of followers to receive your copy of our Readers’ Choice: 253 Books About France (2014), including books about Architecture, Interiors and Gardens; Arts; Biography; Children; Culture; Fashion; Food and Wine; Memoir; Mystery; Novel; Science; Travel; and War, along with email notifications of new posts on the website.

Once subscribed, you will be eligible to win—no matter where you live worldwide—no matter how long you’ve been a subscriber. You can unsubscribe at anytime. We never sell or share member information.

Praise for Five Nights in Paris

“The joy of his writing is to realize that, even after living there for two decades, Paris still provides him with new avenues to explore…No one can successfully write about Paris unless they truly love every nuance, oddity, and secret of her life; here, the author shines. Baxter’s knowledge of those who have written about Paris—for years, he has collected such work—will lead readers to all sorts of corners that do not show up in any tourist guides.”—Kirkus

“An entertaining mix of amusing autobiography and fluent expertise. … Baxter makes after-dark visits to the sites of once fashionable brothels and jazz clubs, follows the scent of perfume, and sumptuously indulges his passion for food, writing, at each turn, with wit and rapture.” —Booklist

Interview: French Impressions: John Baxter’s “Five Nights in Paris” – from the late-night haunts of the city’s most legendary artists and writers, to the scenes of its most infamous crimes published on A Woman’s Paris®.

Five Nights in Paris: After Dark in the City of Light (excerpt)

THE LADY AND THE UNICORN.

by John Baxter

Tour companies offering Paris holidays propose “five nights” in the city when they really mean “five days.” Attractions dwindle at night. Except for the Louvre, which stays open to 8.45pm on Wednesday and Friday, most museums, parks and galleries close when the sun goes down. Was there really no more stimulating way to spend an evening in Paris than an American movie, a four-course dinner on a bateau mouche, or a stroll down the Champs-Élysees?

But the effectiveness of a guided tour depended on being able to point things out. How could that be done in darkness?

I don’t often visit the Museum of the Middle Ages, housed in the old abbey of Cluny on the corner of Boulevard Saint Germain and Boulevard Saint-Michel. Its lamenting saints and agonized Christs always leave me feeling morose. One can’t just slip in for a few moments as I often do into the church of Saint Sulpice or the former chapel of Maria de Medici’s palace, these days the Musée de Luxembourg.

Rather, the Cluny’s a place for wet Wednesdays in February, the architectural equivalent of those scratchy goat-hair shirts once worn by penitent monks. I wouldn’t have visited it on this occasion had they not been digging up the sidewalk on Boulevard Saint-Michel. Crossing to avoid the road works brought me up against the railings around it, and something clicked.

The doorman peered into my carrier, grimaced at the bunch of celery sticking out the top, but placed it behind his desk without asking why someone would choose, in the middle of the morning’s shopping, to browse a museum of medieval antiquity.

My visit was brief. I needed to look at only one room – the one displaying the tapestries of the Lady and the Unicorn.

These six hangings cover the walls of a circular room at the heart of the museum, kept in gloom to preserve their colors. This morning, the gallery was almost empty, so, rather than peering over the heads of coach parties from Yokohama or Capetown, I could approach them almost close enough to touch.

Woven around the time of Columbus, they ended up in the Chateau de Boussac in central France. Who made them and why are mysteries still unsolved. Supposedly a Prince Zizim, pretender to the Ottoman Empire and a prisoner in the chateau, commissioned them for his fiancée back in Constantinople. They were rediscovered in the nineteenth century by novelist Georges Sand. She alerted fellow writer and amateur archaeologist Prosper Mérimée. Best known for writing the story on which Bizet based the opera Carmen, Mérimée, in one of those appointments one can’t imagine being made anywhere but France, was also Inspector-General of Ancient Monuments. Horrified that visitors were snipping pieces as souvenirs, he campaigned to acquire them for the nation.

All six show a similar scene. On a deep red background strewn with blossoms, a woman in a robe, accompanied by her maid, dallies with a lion and a unicorn while rabbits, ferrets and squirrels scamper among the grass and wildflowers. In the first of the series, the maid pumps the bellows of a portative organ as her mistress picks out a tune. In another, she offers her a box of candies, and in a third the lady toys with a wreath of flowers, one of which her pet monkey sniffs. The sixth tapestry incorporates the enigmatic text “À Mon Seul Désir,” which might mean “to my sole desire” or “by my will alone”, or, at a stretch, “love desires only beauty of soul.”

When I emerged after just ten minutes, the doorman rolled his eyes and handed back my groceries, assuming I’d just dropped in to use the bathroom. In fact, I’d wanted to confirm something read years before – that the tapestries were inspired by the five senses. The organ represents hearing, the candy relates to taste; the monkey’s flower signifies smell, and so on.

Why not base my night walks on the five senses also? If they were sufficient for the master of the Lady and the Unicorn, they should be good enough for me.

GARDENS.N

“We should have a garden,” said Marie-Dominique thoughtfully when we moved into our Odéon apartment. She might as well have said, “We need a cow up here.” The terrace, two meters deep and fifteen long, had all the horticultural promise of a four-lane freeway. Floored in galvanized steel, it was fenced off from the sheer drop to the street by some utilitarian square-section bars in Sing Sing green. Two ancient rose trees, stark as crucifixes, languished in cement pots. Add the fact that it was six floors up a serpentine staircase, with no elevator, and the task seemed hopeless.

But never under-rate a Parisienne’s sense of purpose. Today, rose bushes and conifers screen the view over the roofs towards Notre Dame. Revived by food and pruning, the old roses explode annually with giant pink blooms that wave out over rue de l’Odéon, to the wonder of the sixth arrondissement. Our cat Scotty performs daredevil gymnastics on the trunk of an acacia five meters tall. The metal floor has disappeared under Astroturf and the fencing behind ivy, honeysuckle and grape vines. Irises bloom in pots, and a mini-jungle of annuals flourishes in an Edwardian galvanized steel bathtub that we souvenired at midnight from a benne, as the French call a dumpster.

But never under-rate a Parisienne’s sense of purpose. Today, rose bushes and conifers screen the view over the roofs towards Notre Dame. Revived by food and pruning, the old roses explode annually with giant pink blooms that wave out over rue de l’Odéon, to the wonder of the sixth arrondissement. Our cat Scotty performs daredevil gymnastics on the trunk of an acacia five meters tall. The metal floor has disappeared under Astroturf and the fencing behind ivy, honeysuckle and grape vines. Irises bloom in pots, and a mini-jungle of annuals flourishes in an Edwardian galvanized steel bathtub that we souvenired at midnight from a benne, as the French call a dumpster.

Getting that tub into the car, back to the apartment and up the stairs was just one triumph in two decades of sweat and swearing, bad backs, blistered hands, and incredulous “You must be kidding!” stares as deliverymen with sacks of potting mix glared up the stairwell from the ground floor. Nor did the exposed location welcome these new arrivals. In summer we occasionally needed to drench the plants twice daily against a sirocco that coated the leaves with fine red dust from the Sahara, while frost killed a lively wisteria and even shattered the inch-thick stoneware of the antique pickling pot in which we’d planted it.

But now we couldn’t live without the garden. In spring and summer, the French windows are almost permanently open, turning the terrace into an extension of our living room. Croissants and coffee in the morning, drinks in the evening, coffee after dinner – all taste better amid the fragrance of growing things. And on summer evenings, when we water the plants in the velvet night, Voltaire’s “We must cultivate our garden” seems more than simply advice to mind your own business. Maybe, as much as we are looking after our garden in the sky, our garden is looking after us.

Such thoughts place us in good company. French intellectuals who’ve never been closer to horticulture than watering a window box go into rhapsodies over the significance of gardens. Even Louis Aragon, arguably the least practical and high-minded of the Surrealists, exploded with almost incoherent enthusiasm at the mere thought of them.

“Among your flower beds and box tree alcoves, man strips off old habits and returns to a language of caresses, to a childishness of water-sprinkling. He himself, as he whirls round with wet hair, is the sprinkler in the sun. He is the rake and the spade. He is the chip of rock. Gardens, you resemble otter-skin sleeves, lace handkerchiefs, liqueur chocolates.”

All over the city, tiny parks and squares replicate this sense of nature under control. Shop windows onto French thought, they invite reflection. Henry Miller, passing through Place Furstenberg daily from his hotel on rue Bonaparte, saw more than one lesson in the stately chestnuts and plane trees of this secluded little square – circle, actually -tucked away between boulevard Saint Germain and rue Jacob.

“Looks different now, at high noon. The other night when I passed by it was deserted, bleak, spectral. In the middle of the square four black trees that have not yet begun to blossom. Intellectual trees, nourished by the paving stones. Like T.S. Eliot’s verse. Here, by God, if Marie Laurencin ever brought her Lesbians out into the open, would be the place for them to commune.”

My favorite among Paris parks is the Vert Galant, the tiny point thrust into the current of the Seine from the end of the Île de la Cité. When we lived on Place Dauphine, on the other side of Pont Neuf, I often came here at night, communing – or hoping to – with the spirit of Henry IV, nicknamed “Le Vert Galant.” (A “Green Gallant” is a man who remains virile despite his age.) His equestrian statue up at street level still stands guard over the park named for him.

Though a lively community of rats keeps the casual walker away at night, nocturnal wanderers find their scuttling no more disturbing than the rush and suck of dark waters and the clack and swish of bare willow fronds in the night wind. If any isle was ever full of voices, this is it, though they are the kind that lull rather than alarm; murmurings as soporific as Caliban’s “voices that, if I then had waked after long sleep, will make me sleep again.”

If there are parks that truly speak to me, that breathe that unique scent which no visitor to Paris ever forgets, they are not Buttes-Chaumont or the Luxembourg or even the Vert Galante but small anonymous suburban spaces fenced in behind railings, with a few benches, often with a children’s playground at one end and an area covered in asphalt for playing ball games. Trees hide them from the surrounding buildings – or perhaps shield the buildings from the sight and noise of children at play. In winter, foliage falls, blows and gathers in corners – the dead leaves about which Jacques Prévert wrote in one of his best known poems and most popular songs.

“I scoop up the dead leaves,

Of memories and regrets

But my faithful, silent love

Smiles always, and thanks life.”

SCENT 1.

The first time I remember a fragrance ravishing my senses had nothing to do with perfume. On a hot night in Los Angeles, visiting an old apartment house near the beach at Santa Monica, I walked into the courtyard, to be engulfed in the perfume of Cestrum nocturnum – night-blooming jasmine, also called Lady of the Night. Banks of it loomed out of the darkness on both sides. A fountain a few yards away, tiled in orange and brown, crawled with thousands of ladybugs. They tumbled and struggled in a frenzy. Nothing living could resist this stifling blitzkrieg.

Such an epiphany was rare, since I have the olfactory equivalent of a tin ear. My nostrils had practically to touch the surface of wine before I got even a whiff of bouquet, and if Marie-Dominique asked my opinion of her new perfume, her hair had to be tickling my nose before I smelled anything.

I could tell the difference between perfume and no perfume, but not much more. When a woman held out the wrist on which she’d just dabbed something and asked “What do you think of this?” I wasn’t so stupid as to say “Don’t ask me. I can’t smell a thing.” A selection of evasions existed, and I became adept at their use. “Mmmm….interesting. Is it French?” worked most of the time. If it looked too expensive, I’d also had some success with “It’s lovely – but is it you?”

If I liked anything about perfume on women, it was the idea of it; the element of calculation it implied. Men generally want to be accepted for what they are, women for what they’ve become. Men seldom enjoy dressing up. Each women, on the other hand, is an individual work of art; a creation, intended to exhibit her skill at presentation. Speaking for myself, but I think also for many men, I find the most attractive element of female beauty its artificiality. And to that, perfume is crucial.

A few years ago, I visited the headquarters of the Fragonard perfumerie in Grasse, on the Côte d’Azur. One enters their building from the street, then, since it’s built on a cliff, descends level by level, past its offices, its museum, its workshop, to the lowest, which houses a shop the very air of which seems to have been entirely replaced by perfume.

As the vendeuse let me sniff the various essences and fragrances I’d promised to buy for my wife and daughter, I could only think of the fortunate husbands and lovers to whom these women went home. Drenched in perfume day after day, how did they smell? Of what did they taste ? French women who wish to make themselves particularly alluring to their lovers drink quantities of tea perfumed with orange or jasmine. If they consume enough -a full pot, according to the best advice -the scent manifests itself in their …um, juices. Was it the same with these girls? Did the fragrances they sold penetrate into their very cells? If I hadn’t been due in Antibes the next day on a film shoot, I would happily have devoted a few days to finding out.

SCENT 2.

Intellectually, I knew how Paris should smell: anise, absinthe, roasting chestnuts, coffee, mixed with the rival perfumes worn by women in the street. In practice, I smell almost nothing. Occasionally, the tang of burning charcoal catches my nose as I pass Giovanni, the chestnut seller at his long-time pitch outside Deux Magots. I sometimes sniff burning sugar from a creperie if the cook is, just at that moment, smearing the pancake with honey or Nutella, or if a maker of barbe à papa is spinning coloured sugar into what we as kids called Fairy Floss. Otherwise, I might as well have my head in a sack. Do you wonder that, in planning a smell walk, I recruited an expert?

Kate McLean has turned her finely-tuned sense of smell into an area of expertise. Sniffing out rare odors with the precision of a truffle hound, she traps them on absorbent paper for incorporation into “smell maps” that delineate a city not in geographical highs and lows but as overlapping zones of plant, animal and chemical scents.

As a blind person exists in a world of touch and sound, Kate swims in a world of smells. In person agile and lean – as a hobby she runs marathons – she evokes both a forest animal and the dogs that hunt them. She’ll freeze “on point” as her nose traps a transient thread of smell.

“Ah! Get that? Roses….”

Her nose swings like a compass needle to point at a bush of yellow Desprez à Fleurs Jaunes in a tiny garden across the street.

“…. and…..pizza?”

Swiveling back, she nails the overweight citizen of Perth Amboy New Jersey ambling past us, munching on a slice of quattro stagioni (hold the anchovies).

Montmartre seemed a good place to start. Calculating that it would be easier to begin at the highest point of the butte that dominates Paris to the north and work our way down, we arranged to meet on Place du Tertre.

But Kate flinched, as I did, from the mob filling the square. Traditionally it was at the restaurant Mère Catherine at 6 Place du Tertre that Russian Cossacks in March 1814, flooding into Paris after the defeat of Napoleon, demanded to be served “bystro!” – quickly – and created an enduring term for a café. They’d be pleased to see that the row of postcard sellers and fast-food stalls that used to occupy the centre of the place had become a cluster of sit-down restaurants, above which a few surviving trees poked their heads like drowning giraffes. The alley between where the centre restaurants ended and those fringing the square began was cruised by predatory street artists who, if you let them catch your eye, homed on you with sketch pad and pastels, hungry to imprison you on paper.

As a miasma of hot oil, burned sugar and sweat threatened to drown her sense of smell, we retreated down rue Lamarck to the frontage of Sacré-Coeur. Though tourists had colonized the tumble of steps below the cathedral, the evening breeze swept the air clean and clear, showing the valley of Paris at its best. This view never disappoints.

Looking up at the dusty grey façade of Sacré-Coeur, Kate asked “Should we go inside?”

“If you like,” I said. “Perhaps we’ll find the odour of sanctity.”

Does virtue smell better than sin? The nuns and priests around whom I was raised were as prone as any sinners to body odour and the furtive fart. Certain saints, even after death, were supposed to give off a perfume, usually compared to violets.

It was less common among the living, though the British playwright Alan Bennett sometimes caught a whiff of what appeared to be a heavenly odor. In one case, at an outdoor restaurant in Rome, it turned out to be a waiter’s particularly powerful aftershave, but when Bennett detected it while visiting the country home of Alec Guinness, he was convinced he’d found in that mild, courteous and modest actor the true scent of holiness -until, walking by a grove of balsam poplars, he realised it was their buds that gave off the delicious fragrance, a scent so intense that the Bible celebrates it as the balm of Gilead. It may even have been the myrrh which, with gold and frankincense, the three wise men brought as gifts to the infant Jesus.

Sadly, Sacré-Coeur held no balm of Gilead. The one overpowering smell was paraffin wax. In every alcove, before every statue, and at both entry and exit doors, banks of candles blazed. Two Euros bought a tiny candle in a metal cup that burned for about fifteen minutes. For ten euros, you could have a red or yellow glass tumbler filled with enough wax for an hour.

“It reminds me of childhood birthday cakes,” Kate said. We both knew she was looking for a bright side in the pervasive commercial gloom. During my Catholic boyhood, each church had only one bank of candles, payment was optional, and the air was perfumed with that distinctive merging of heat and honey that signifies burning beeswax -the closest approximation, to me anyway, of the true odour of sanctity.

As we were ready to leave the cathedral, an idea struck me. While no scent would cling to stone, the wood screening the entrance and exit might, over a century, have soaked up some odors. Putting our noses to the dark oak, we sniffed for a distinctive signature. Did the faintest trace linger of the incense burned here in decades of high masses, the floral arrangements of a thousand funerals….? Then Kate nudged me. A large security man was eyeing us suspiciously. We escaped into the twilight and the more familiar though less saintly smells of sweat and sore feet.

Photo: Rudy Gelenter

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is the author of the memoirs: The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s, and Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918. A native of Australia, he currently lives with his wife and daughter in Paris—in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is the author of the memoirs: The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s, and Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918. A native of Australia, he currently lives with his wife and daughter in Paris—in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

Since moving to France, John has published biographies of Federico Fellini, Luis Bunuel, Steven Spielberg, Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, Josef von Sternberg, Robert De Niro, and the author J.G. Ballard. He has also written five autobiographies, including A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. His most recent books are Chronicles of Old Paris and The Paris Men’s Salon, a selection from his uncollected prose pieces. John’s translations of Morphine, by Jean-Louis Dubut de la Forest and Fumée d’Opium, by Claude Farrère, have also been published by HarperCollins, the latter as My Lady Opium.

John has co-directed the annual Paris Writers Workshop and is a frequent lecturer and public speaker at universities and writers workshops. His hobbies are cooking and book collecting (he has a major collection of modern first editions). When not writing, he can be found prowling the bouquinistes along the Seine or cruising the internet in search of new acquisitions.

In 1974, John was invited to become a visiting professor of film at Hollins College in Virginia, U.S.A. While in the United States, he collaborated with Thomas Atkins on The Fire Came By: The Great Siberian Explosion of 1908, a highly successful book of scientific speculation, and wrote a study of director King Vidor, as well as completing two novels, The Hermes Fall and Bidding. (Facebook) (Website)

Photo: Rudy Gelenter

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post John Baxter’s “Paris at the End of the World” – Patriotism transforming fashion (excerpt). Preeminent writer on Paris, John Baxter brilliantly brings to life one of the most dramatic and fascinating periods in the city’s history. Uncovering a thrilling chapter in Paris’ history, John Baxter’s revelatory new book, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, shows how this extraordinary period was essential in forging the spirit of the city we love today.

Readers’ Choice: 253 Good Books About France (2014). Your quest is to dig below the surface, peek behind the façade, where lurks a story, rumor, recipe or fossil. We have an eagerness to explore fresh ideas, to forge powerful relationships and build a community. Readers, we invite you to draw close this narrative, woven on A Woman’s Paris, a narrative that has come to life, to discover secrets of the past and take part in shaping the future. Become a part of our conversation. We celebrate the art and ideas of people from every place and every heritage.

The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944 – Excerpt from Ronald C. Rosbottom’s “When Paris Went Dark” (Part One). June 14, 1940, German tanks entered a silent and deserted Paris and The City of Light was occupied by the Third Reich for the next four years. Rosbottom illuminates the unforgettable history of both the important and minor challenges of day-to-day life under Nazi occupation, and of the myriad forms of resistance that took shape during that period. August 2014 marks the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris, perfect timing for Ronald C. Rosbottom’s riveting history of the period.

Tilar J. Mazzeo’s “The Hotel on Place Vendôme” – Hôtel Ritz in Paris: June 1940 (excerpt). Tilar J. Mazzeo, author of the New York Times bestseller The Widow Clicquot, and The Secret of Chanel No. 5. This riveting account uncovers the remarkable experiences of those who lived in the hotel during the German occupation of Paris, revealing how what happened in the Ritz’s corridors, palatial suites, and basement kitchens shaped the fate of those who met there by chance or assignation, the future of France, and the course of history.

Gerri Chanel’s “Saving Mona Lisa” on the battle to protect the artistic heritage of France during World War II (part one). In this engaging and suspenseful book, Gerri Chanel describes the connections between the museum and its curators to other wartime developments in France. Superbly researched, Saving Mona Lisa is a compelling true story of art and beauty, intrigue and ingenuity, and remarkable moral courage in the face of one of the most fearful enemies in history.

For Love or Money: Marriage and Divorce in the French capital (1880-1941) – Excerpt from Nancy L. Green’s “The Other Americans in Paris”. Nancy L. Green introduces us for the first time to the Right Bank American transplants. There were newely minted American countesses married to foreigners with impressive titles, American women married to American Businessmen, and many discharged American soldiers who had settled in France after World War I with their French wives. The book details the politics of citizenship, work, and business, and the wealth (and poverty) among the Americans who staked their claim to the City of Light.

Mireille Guiliano’s “Meet Paris Oyster” on the Parisians’ love for them (excerpt) – part one. Mireille Guiliano, a former chief executive at LVMH (Veuve Clicquot), is “the high priestess of French lady wisdom” (USA Today) and “ambassador of France and its art of living” (Le Figaro). She is the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller French Women Don’t Get Fat: The Secret of Eating for Pleasure, as well as French Women Don’t Get Facelifts. With her characteristic wit, wisdom, and storytelling flair, Mireille will soon have you wanting to eat oysters at least every week. Including a recipe for Oyster Vichyssoise.

Patricia Wells’ “The Food Lover’s Guide to Paris” on Restaurants, Bistros, and Brasseries (excerpt). Patricia Wells, author of the award-winning Bistro Cooking, and for more than two decades the restaurant critic for The International Herald Tribune, takes readers, travelers and diners to the best restaurants, bistros, cafés, patisseries, charcuteries, and boulangeries that the City of Light has to offer. Including Willi’s Wine Bar’s Bittersweet Chocolate Terrine—the irresistible chocolate dessert that is one of Patricia’s Paris favorites.

Text copyright ©2015 John Baxter. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com