French Impressions: Gerri Chanel’s “Saving Mona Lisa” thus began the biggest evacuation of art and antiquities in history

22 Thursday Jan 2015

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Interviews

Tags

Books about France (2014) A Woman's Paris, Dreaming in French Alice Kaplan, France, France Monthly, French Resistance World War II, In the Garden of Beasts Erik Larson, Louvre Paris, Midwest Book Review, Monuments Men movie, Occupation of France World War II, Paris, Paris Blues Andy Fry, Provenance Laney Salisbury Aly Sujo, Rose Valland Le Front de l'Art, Saving Mona Lisa Gerri Chanel Heliopa Press, The Other Americans Nancy L. Green, The Sweet Life in Paris David Lebovitz, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein Bernard Faÿ and the Vichy Delemma Barbara Will, Vichy government France World War II, W. Scott Haine Simone De Beauvoir Paris, When Paris Went Dark Ronald C Rosbottom, Wine and War Donald Kladstrup Petie Kladstrup

Share it

Gerri Chanel is a prize-winning freelance journalist, professor at the City University of New York and a former business consultant. She lived in Paris for five years, where, in addition to writing and teaching, she also held wine and cheese tastings for tourists that were rated among the top Paris attractions on TripAdvisor. While in France, Gerri also began the research for her book, Saving Mona Lisa. As part of her research for the book, she combed through various French archives and had access to the few remaining living witnesses of the events. Gerri now divides her time between New York and Paris. For more information, visit: (www.SavingMonaLisa.net)

Gerri Chanel is a prize-winning freelance journalist, professor at the City University of New York and a former business consultant. She lived in Paris for five years, where, in addition to writing and teaching, she also held wine and cheese tastings for tourists that were rated among the top Paris attractions on TripAdvisor. While in France, Gerri also began the research for her book, Saving Mona Lisa. As part of her research for the book, she combed through various French archives and had access to the few remaining living witnesses of the events. Gerri now divides her time between New York and Paris. For more information, visit: (www.SavingMonaLisa.net)

In late summer 1939, just days before France declared war against Germany, the Louvre staff conducted the largest museum evacuation in history in record time, then managed to keep its art and antiquities out of the hand of Nazi occupiers throughout the years of occupation that followed.

The Mona Lisa was moved six times during the war, traveling in a custom-made red-velvet lined case. The museum’s other treasures also moved from countryside chateau to chateau, where curators and guards who risked their jobs and lives to keep the art and antiquities safe looked after them. Due to their heroic efforts over the course of the war, the Louvre and its evacuated art miraculously survived not only the appetites of Hitler and his henchmen—often supported by the complicit Vichy government—but also gunfire, shells, bombs, and damage from a crashed plane.

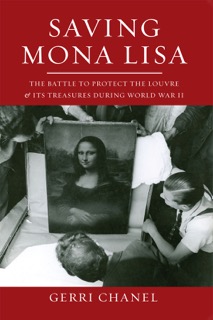

Saving Mona Lisa: The Battle to Protect the Louvre & its Treasures During World War II by Gerri Chanel is an engaging and suspenseful book that also describes the connections between the museum and its curators to other wartime developments in France. Superbly researched and accompanied by riveting photographs of the period, Saving Mona Lisa is a compelling true story of art and beauty, intrigue and ingenuity, and remarkable moral courage in the face of one of the most fearful enemies in history. Author Gerri Chanel provides new insights and narrative, images and new research, and tells how the Louvre’s staff accomplished these monumental feats in Saving Mona Lisa: The Battle to Protect the Louvre and its Treasures During World War II (2014, Heliopa Press). To purchase Saving Mona Lisa, visit: (www.SavingMonaLisa.net)

Saving Mona Lisa: The Battle to Protect the Louvre & its Treasures During World War II by Gerri Chanel is an engaging and suspenseful book that also describes the connections between the museum and its curators to other wartime developments in France. Superbly researched and accompanied by riveting photographs of the period, Saving Mona Lisa is a compelling true story of art and beauty, intrigue and ingenuity, and remarkable moral courage in the face of one of the most fearful enemies in history. Author Gerri Chanel provides new insights and narrative, images and new research, and tells how the Louvre’s staff accomplished these monumental feats in Saving Mona Lisa: The Battle to Protect the Louvre and its Treasures During World War II (2014, Heliopa Press). To purchase Saving Mona Lisa, visit: (www.SavingMonaLisa.net)

Subscribers, Saving Mona Lisa by Gerri Chanel, award-winning freelance journalist and professor at the City University of New York. Free book giveaway to two subscribers ends January 26, 2015. An $18.00 U.S. value (2014, Heliopa Press, LLC).

Free Subscription: Join our thousands of followers to receive your copy of our Readers’ Choice: 253 Books About France (2014), including books about Architecture, Interiors and Gardens; Arts; Biography; Children; Culture; Fashion; Food and Wine; Memoir; Mystery; Novel; Science; Travel; and War, along with email notifications of new posts on the website.

Once subscribed, you will be eligible to win—no matter where you live worldwide—no matter how long you’ve been a subscriber. You can unsubscribe at anytime. We never sell or share member information.

Praise for Saving Mona Lisa: The Battle to Protect the Louvre and its Treasures During World War II

“…[W] ill prove to be a monument to courage. Especially recommended to the attention of non-specialist general readers with an interest in World War II history and true tales of extraordinary heroism, “Saving Mona Lisa: The Battle to Protect the Louvre and its Treasures During World War II” should be considered an essential, core addition to academic library 20th Century European History collections.” — Midwest Book Review

“… [A] thoroughly detailed account of this intriguing chapter in French history. Rather than aggrandizing an already extraordinary story, her narration of the Mona Lisa’s miraculous survival – in the face of Hitler’s henchmen, heavy bombardment and the complicit Vichy government – lets the facts speak for themselves and they’re all the more compelling for it.” — France Monthly

Photo credit: Michelle Lawson

Excerpts:

Chapter 11: Gerri Chanel’s “Saving Mona Lisa” on the battle to protect the artistic heritage of France during World War II (part one), published on A Woman’s Paris®.

Chapter 16: Gerri Chanel’s “Saving Mona Lisa” keeping a close eye on the whereabouts of the Louvre’s treasured ‘Diana” (part two), published on A Woman’s Paris®.

INTERVIEW: Saving Mona Lisa: The Battle to Protect the Louvre and its Treasures During World War II

In August 1939, curators at the Louvre nestled the world’s most famous painting into a special red velvet-lined case and spirited her away to the Loire Valley. Thus began the biggest evacuation of art and antiquities in history. As the Germans neared Paris in 1940, the French raced to move the masterpieces still further south, then again and again during the war, crisscrossing the southwest of France. At times, Mona Lisa slept at the bedside of curators who were painfully aware of their heavy responsibility.

Throughout the German occupation, the Louvre’s staff fought to keep the priceless treasures out of the hands of Hitler and his henchmen and to keep the Louvre palace safe, many of them risking their jobs and their lives to protect the country’s artistic heritage. Saving Mona Lisa is the sweeping, suspenseful narrative of their battle.

Above all, France was obliged to save the spiritual values it held as an integral part of its soul and its culture. To put its artworks, its archives and its libraries out of harm’s way was indeed one of our country’s first reflexes of defense. —Rose Valland, Le Front de l’Art

(Rose Valland (1898-1980) was a French art historian, a member of the French Resistance, a captain in the French military, and one of the most decorated women in French history. She secretly recorded details of the Nazi plundering of National French and private Jewish-owned art from France, and working with the French Resistance, saved thousands of works of art.)

AWP: You are author of Saving Mona Lisa. What inspired you to write this book?

GC: Ironically, it was a statement in a documentary film that ultimately turned out not to be true. The narrator described how the French purportedly hid one of the museum’s paintings from the Germans by using it as a false ceiling in a Paris restaurant. I wanted to find out more about such a tantalizing tidbit. When I searched the Internet for more information, I was drawn into a treasure hunt for facts about what became increasingly evident was an amazing true story. Ultimately, I learned that the French didn’t attempt to hide the artwork from the Germans at all.

AWP: You entrench your work in a different part of Paris’ past, taking stock of a city that did not fire a shot and mapping the transformation of a different type of occupation—to keep the priceless treasures from the Louvre out of the hand of Hitler and his henchmen and to keep the Louvre a safe place to protect the country’s artistic heritage. Your research is exemplary. How did you accumulate and obtain this information? Was it primarily in French? What were the challenges, and how did you uncover these stories?

GC: Many of the source materials—particularly archives and memoirs—were in French. Certain documents were in German; for those, I obtained the help of a translator. One of the most pleasurable aspects of the research was the access to the Louvre’s archives, which were then located within the Louvre palace itself (now being moved to a special archive facility in a Paris suburb). It was an overwhelming feeling to be allowed behind the scenes though a door marked “public not allowed”, and it gave me goose bumps to touch actual reports and correspondences to and from the curators and the Louvre director.

It was a challenge to uncover the story since details were found in so many different sources, including archives, memoirs, newspaper articles, interviews, academic theses, and other places. I looked through many thousands of documents in multiple archives in and around Paris, and carefully scoured books for possible links to other possible sources. The entire process was a like a wonderful treasure hunt. For example, in a Google search for information about a plane crash a block from the Louvre in 1943, I came upon a reference to a memoir by a young Parisian fireman who witnessed the aftermath of the crash. Without the Internet, I can’t imagine how I would have known about the existence of this obscure book. I tracked it down, and found that it not only had information about the crash that was relevant for the Louvre’s story, it also had a delicious recounting of how the young, bored patrolmen guarding the largely empty wartime Louvre amused themselves.

AWP: What part did Americans play in the battle to protect the Louvre and the treasures of France during World War II?

GC: Americans played an almost nonexistent role in the protection of the Louvre and its treasures since the French did such a successful job on their own. In the immediate aftermath of the liberation of Paris and the Loire area, when travel of personnel was particularly difficult, the “Monuments Men” lent a hand measuring humidity in storage areas and they provided “Keep Out” signs in English for the art storage depots. However, the Monuments Men played a much more significant role in protecting other treasures of France after the D-Day landing, such as ensuring that French monuments and private residences were secured from looting and that war-damaged buildings of historical significance in Normandy and elsewhere in France were preserved rather than being destroyed in the interest of military expediency (such as using building debris to fill potholes to make roads more easily traveled by military vehicles).

AWP: When you started writing Saving Mona Lisa, did you have a sense of what you wanted to do differently from other accounts you had seen?

GC: Yes, I was clear about this from the start, even though I didn’t come across many of the specifics until later. All the other accounts I had seen were piecemeal ones included in works more broadly focused on Nazi art looting of Jewish and other art and objects. I wanted do to a story that placed the Louvre and its staff front and center and told the whole story of that battle. The book does address the issue of German looting of Jewish art, but the Louvre and its artwork and curators remain the central focus.

AWP: What was the most surprising thing you learned?

GC: The two biggest surprises came near the beginning of my research. First, that the French did not hide the Louvre’s art from the Germans. They moved it to keep it safe from areas they considered vulnerable to the effects of war, such as bombing, ground battle, etc. And second, the Germans learned where the artwork was right at the beginning of the Occupation. The fact that they knew where the treasures were makes the fact that the French managed to protect it even more compelling.

AWP: You have made some very interesting discoveries about World War II through research and archives. Have you found an underlying message that is especially significant for us today?

GC: Yes, there is an overriding and timeless message in the many ways the Louvre’s director and curators fought the German attempts to get the art and in the ways the French resisted overall. The message is that there are infinite ways to fight “evil”—whatever that entails, that each person really can make a difference and that even small efforts are important because they can have a cumulative effect.

AWP: But while the publicly owned art of the Louvre was largely protected during the war, privately owned Jewish collections from galleries and homes were looted on a massive scale. What are the efforts to find owners of stolen Jewish treasures and to return seized items to them that continue to this day?

GC: There are so many current efforts across the world that it is impossible to describe them here. But, it is also interesting to consider why efforts are still required 70 years later, and that question has a more concise answer. In some cases, families were completely exterminated and so nobody remained to come forward. In other cases, ownership records were destroyed. In other cases, all that remained were childhood memories of seeing a painting on a relative’s parlor wall. Also, undertaking a claim, especially against an institution such as a museum, is expensive and in some situations, descendants have lacked the funds to pursue a claim. Another complicating factor is that during the war, many art dealers knowingly traded in looted art, and so they hid or destroyed receipts and other records that would show provenance. Moreover, in many cases, there is a complicated chain of wartime and subsequent ownership since Germans sold many artworks to get hard currency, or exchanged them for different works. Many works were dispersed through the art trade, exchange or gift during the war or afterwards and could be anywhere in the world. Yet other complications for restitution claims involve privacy laws and conflict in laws from one jurisdiction to another.

Efforts have grown in recent years for multiple reasons. One major driver is the information-sharing power of the Internet, and databases are flourishing, though much more work is needed to connect them. Also, more archives are open for researchers due to the passage of time, and a recent surge of interest and attention has arisen since the hidden stash of looted art owned by Cornelius Gurlitt was uncovered in 2012.

AWP: What was the most surprising thing you learned about the war from a distance of 75 years at its start? Is there one statement that channels everything you have uncovered about World War II?

GC: What resonates most, especially after reading so many memoirs written in the post-war years, is that war is about people. This sounds obvious, but as I recall learning history in school, World War II (like the rest of history) was taught in terms of battles, borders and political parties. It focused very little, if at all, on what war was like for individual people. What resonated deeply with me was how different war seems when taken to an individual level. For example, news reports of bombings during the war cite figures for “casualties,” an antiseptic word that doesn’t reflect the raw reality that fathers, mothers, and children were killed, maimed and orphaned. Books may say that Parisians were hungry during the war, but that isn’t the same as knowing that someone had to wait in a frigid line for many hours just for a corner of cheese and that fuel for cooking was difficult or impossible to obtain. Likewise, a general mention of the French Resistance doesn’t give substance to the infinite very personal acts of resistance, from jostling German soldiers in the Paris métro to delaying a delivery or smuggling underground writing to Paris in a lipstick tube. All these things give a more tangible sense of what World War II was like for Parisians.

Likewise, very personal motivations are sometimes overlooked in explaining why events occurred. For example, some accounts of the Nazi looting of art during World War II don’t explain that the large-scale looting of Jewish art collectors and gallery owners in Paris and throughout Europe derived in large part from a specific personal quirk: Hitler’s belief that he was a great artist. In a 1939 interview, he said, “future historians will remember me, not for what I have done for Germany, but for my art.” Chilling, isn’t it?

WRITING

AWP: You have a very shrewd grasp of how memory works, often in strange ways. How did this play a part in writing this book?

GC: Writing history is a tricky thing since it can be difficult or impossible to determine an objective “truth.” Also, contemporaneous accounts are filtered through immediate experience and historical accounts can be filtered through a specific perspective or agenda and sometimes contain errors. Also, memory plays various tricks; for example, scientific research shows that our memories are colored by emotion and of course, we simply forget some facts over time. All these things mean that memoirs, like any historical source, need to be understood with a skeptic’s antennae. More than once in my research, I found a wartime report that didn’t quite jive (in minor ways) with how the same event was recounted in a memoir or other recollection by the same person many years later. So it required a sort of “triangulation” with a separate source to see which version seemed correct.

AWP: How does your previous scholarship and as international business consultant influence your work?

GC: Almost everything I’ve done in my career has involved significant research. Any kind of research requires a similar set of skills—curiosity, skepticism, creativity (often needed to identify sources), and sometimes unremitting persistence. All of these skills allow me to root out interesting and unusual connections. Likewise, teaching, consulting, and writing all involve clear and meaningful communication.

AWP: Why did you feel that now, in particular, would be the right time to publish your book, Saving Mona Lisa?

GC: There was no particular consideration of the right time; it was just when I happened to develop the idea. But it turned out to be good timing in several ways, being released just before the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landing and the liberation of Paris and not long after the release of the Monuments Men film. The film didn’t address the events in Saving Mona Lisa, but it raised awareness of and interest in the topic of art during World War II.

AWP: What do you think it is about Saving Mona Lisa that makes readers connect in such a powerful way?

GC: One reason readers can connect is because so many are familiar with the Louvre, and, of course, its best-known painting, so they can relate to the incredible effort involved in keeping it all safe during the war. The story also makes people reflect on a larger scale about the value of protecting a society’s cultural heritage. On another level, I read recently that when people read any story, they’re looking for a hero, whether that “story” is a literary novel or a detective series. To the extent that is true, Saving Mona Lisa is a compelling story of heroism by many people under terrible circumstances.

AWP: Could you talk about your process as a writer?

GC: I used to wish I were the kind of (imaginary!) writer who could create a formal detailed outline and then move forward with great efficiency. But, I’ve learned that any work of substance comes from a process that is inherently inefficient to some extent—creativity is simply “messy,” outline or not. I’ve also found that some of the most compelling elements of a story become evident later in the process. So, though I start with a relatively clear idea of where I’m headed, the process is not linear. After a first round of research, as I begin to flesh out the story and organize the narrative, I might wonder why something happened or spot a connection that wasn’t evident earlier, which leads to a new research loop down another path. The hardest part is resisting the temptation to stroll down each interesting path too long! The new information often leads to a shift in the flow of the story.

Overall, it seems to me that there’s a point in any writing project where it seems to gel and “tell the writer” what it wants to be. At that point, you just need to listen.

With Saving Mona Lisa, I knew from the very beginning that there was a story to tell about how the Louvre worked to saved its art during the war, because I already knew bits and pieces of what happened. But it wasn’t until I was deeper into the research that I came across many of the most fascinating aspects, and I was still dipping back into more limited research as I was getting ready to finalize the book and then incorporating what I found. Also, throughout the process, I kept coming across new compelling photographs that I wasn’t aware of earlier or a new person to talk to. At each step, another layer of the story unfolded.

ART OF LIVING

AWP: When you moved to Paris how did you grapple with the cultural differences? Can you share the moment when you knew it had changed for you?

GC: One challenge was learning that polite behavior is defined differently in different cultures. At a Parisian department store the week I arrived, I approached a security guard and launched directly into what I thought was a polite request for directions to the dressing room. He looked at me with a blank look and said, “Bonjour, Madame.” I smiled, nodded and again asked for the dressing room. Through clenched teeth, he again replied, “Bonjour Madame.” I said hello before I asked again, but didn’t really absorb his message. Then one day, checking out at the grocery store, I asked the cashier for a bag. Perhaps rightfully tired of rude foreigners, he responded, “Bonjour, Madame. On commence avec bonjour.“ Ah.

Another major difference I grappled with is the time it often takes in France to get repairs or paperwork done… it’s often a far cry from “a New York minute.” When the elevator broke in my Paris apartment building, we were told it would be fixed “soon,” then months rolled by. (In New York, people would probably be threatening to sue by the next day). I knew my outlook had changed—in a healthy way—when I realized that instead of stewing about it, I needed to just let it go and appreciate the exercise.

Another difference is the fact that so many local stores still close on Sunday, so I had to learn to plan ahead. Some groceries stores are open Sunday morning, but that still required planning. And it’s no fun to run out of printer ink on a Sunday when you want to work. At first this seemed like an inconvenience, but I quickly realized that a day a week without the ability to do errands except for strolling a wonderful outdoor market is a very good thing. With Sunday closings and extensive summer vacation closings, the French still put joie de vivre ahead of the quest for earning a living in many respects; there’s something important to learn from that.

AWP: What cultural nuances, attitudes, ideas, or habits have you adopted? In which area have you embraced a similar aesthetic?

GC: I think I’ve retained some of the patience I learned while living there. After all, if the electric company doesn’t return my call today, does it really matter? I’ve also embraced some French habits in terms of dress, including a closetful of scarves and having more fun with eyeglass styles (eyeglass shops seem to be on almost every Paris street and there are more and different styles than in the U.S.). Also, one of the things I noticed early in my stay in Paris is that many middle-aged Parisian women, especially in the summer, wear frillier scarves, more clothing trimmed with lace or ruffles and in general aim for an overall younger style than many American women of the same age. There’s less of the idea that at some point, a woman becomes “too old” for certain styles. I’m embraced that too, along with the fact that Parisian women don’t seem to have an expiration date for expressing subtle sexiness in the way they dress. The first time I went into a Paris bank, I couldn’t believe the manager’s décolletage, but eventually realized that it wasn’t at all inappropriate to a French eye!

On a food-related note, having lived five minutes from the famous market street rue Mouffetard and two other wonderful street markets, I now much prefer shopping more often and for fresher, farm-based items.

AWP: What is the best part about living in Paris? In New York?

GC: There are so many great aspects of both cities, even on a mundane day. In Paris, it’s a privilege and joy to be surrounded by so much history and breathtaking beauty, even on the way to the grocery store. Doing errands in Manhattan, on the other hand, I’ve seen TV episodes being filmed and presidential motorcades cruise by, heading to the nearby United Nations. In Paris, many everyday things have a nice ceremonial air about them, like buying flowers. Flower shops are everywhere, the flowers are beautiful and inexpensive and the vendors always ask if they’re for you or for a gift and will wrap them beautifully. New York may not have all those wonderful flower shops, but on the other hand, it’s easier to find any kind of ingredient or food from anywhere in the world than it is in Paris. I really miss the cheese shops of Paris, though, with the variety and incredible freshness, some of the cheeses just days old and the fragrance wafting into the sidewalk.

AWP: Describe your own “Paris.”

GC: On one visit back to the U.S. while I was living in Paris, a relative said, “Tell me about all the fashion shows you go to!” I explained that much my time was spent with less exotic events like work, buying groceries and the everyday kinds of life maintenance we might have anywhere, like figuring out where to buy a replacement battery for my watch. So “my” Paris consisted of more intimate moments, like chatting with the storekeepers in the neighborhood or my neighbors—which in one case evolved into a wonderful arrangement of teaching English to the children of a Vietnamese couple in my building in exchange for hot, home-cooked Vietnamese meals. My Paris included looking out the bus window at dusk, awaiting the moment that the bus crossed the Seine and I could catch the breathtaking view of the bridges and Notre Dame lit up and the Eiffel Tower glowing in the background. My Paris was also endless strolls with a friend exploring every quartier, often along the Seine and we’d eventually stop to have a leisurely bite to eat and glass of wine at a café. As classic as it sounds, not much can top it for a pleasure of life.

AWP: Tell us something we don’t know about Paris—its style, food, culture or travel.

GC: Paris is very much a global, multicultural city, which is something I didn’t fully realize until I was living there. There are cultural institutions, exhibitions and events and restaurants with authentic cuisine from many countries. As a result, I had wonderful opportunities to make friends originally from Vietnam, Tunisia, Spain, and elsewhere.

In terms of travel, France is also an amazingly diverse country in terms of geography, climate, and food compared to its compact size. Luckily, with the fast, efficient trains (well, as long as they’re not on strike…) it’s very easy to get from Paris to far-flung places in a short time. A friend and I took a day trip to Marseille: three hours of comfortable (early) train travel, followed by a full day on the beach, a cruise of the magnificent Calanques (rocky Mediterranean “fjords”), a bouillabaisse dinner and a relaxing ride back to Paris, all in one day.

AWP: Your life is extraordinary. What’s next?

GC: Something unexpected but fascinating always seems to be around the corner, so it’s impossible to know for sure. But another book idea has begun to twinkle on the horizon.

BOOK RECOMMENDATIONS BY GERRI CHANEL

The Sweet Life in Paris: Delicious Adventures in the World’s Most Glorious—and Perplexing—City by David Lebovitz (2011, Broadway Books)

Wine and War: The French, the Nazis and the Battle for France’s Greatest Treasure by Donald Kladstrup and Petie Kladstrup (2002, Broadway Books)

In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin by Erik Larson (2012, Crown)

Provenance: How a Con Man and a Forger Rewrote the History of Modern Art by Laney Salisbury and Aly Sujo (2010, Penguin Books)

Acknowledgements: Alyssa Noel, student of French and Italian, and Journalism at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities and English editor for A Woman’s Paris.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post French Impressions: Ronald C. Rosbottom’s “When Paris Went Dark” – Marking the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris (Part One). Marking the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris, Rosbottom’s When Paris Went Dark weaves a rich tapestry of stories to rediscover from the pavement up the texture of daily life in a city that looked the same but had lost much of its panache. This expansive narrative will fascinate readers who are interested in the history and continuing legacy of World War II.

Andy Fry on the Jazz Age – African American music in Paris, 1920-1960 (part one). The Jazz Age. The phrase conjures images of Louis Armstrong holding court at the Sunset Cafe in Chicago, Duke Ellington dazzling crowds at the Cotton Club in Harlem, and stars like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey wailing the blues away. But the Jazz Age was every bit as much of a phenomenon in Paris, where the French public found their own heroes and heroines at the Folies-Bergère and Casino de Paris.

French Impressions: Nancy L. Green on the “other” Americans; Right Bank expatriates in 20th century Paris. While Gertrude Stein hosted the literati of the Left Bank, Mrs. Bates-Batcheller, an American socialite and concert singer in Paris, held sumptuous receptions for the Daughters of the American Revolution in her suburban villa. History may remember the American artists, writers, and musicians of the Left Bank best, but the reality is that there were many more American businessmen, socialites, manufacturer’s representatives, and lawyers living on the other side of the River Seine. Nancy L. Green recounts the experiences of a long-forgotten part of the American expatriate population.

French Impressions: W. Scott Haine on the origins of Simone de Beauvoir’s café life and the entry of France into WWII (Part one). “Café archives” seldom exist in any archive or museum, and library subject catalogs skim the surface. Scott Haine, who is part of a generation that is the first to explore systematically the social life of cafés and drinking establishments, takes us from the study of 18th century Parisian working class taverns to modern day cafés. A rich field because the café has for so long been so integral to French life.

French Impressions: Barbara Will on Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the intellectual life during wartime France (Part one). From 1941 to 1943, Jewish American writer and avant-garde icon Gertrude Stein translated for an American audience thirty-two speeches in which Marshal Philippe Pétain, head of state for the collaborationist Vichy government, outlined the Vichy policy barring Jews and other “foreign elements” from the public sphere while calling for France to reconcile with its Nazi occupiers. In her book, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, Barbara Will outlines the formative powers of this relationship, treating their interaction as a case study of intellectual life during wartime France.

French Impressions: Alice Kaplan – the Paris years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, on the process of transformation. Author and professor of French at Yale University, Ms. Kaplan discusses her new book, Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, and the process of transformation. By entering into the lives of three important American women who studied in France, we learn how their year in France changed them and how they changed the world because of it. (French)

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2015 Gerri Chanel. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com