French Impressions: Alice Kaplan – the Paris years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, on the process of transformation

16 Tuesday Apr 2013

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Cultures, Interviews

Tags

Alice Kaplan, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, American Association of Literary Translators, Angela Davis, Another November by Roger Grenier, Audrey Hepburn, bohemian Paris, Bringing up Bébé, Columbia University, Critique, Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Susan Sontag and Angela Davis by Alice Kaplan, Duke University, Editions Gallimard in Paris, French Lessons: A Memoir by Alice Kaplan, French literature, German Occupation and Liberation, Givenchy, Guggenheim Foundation, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, John M Musser Chair in French Literature, L'Histoire, Le Point, Lehrman Chair in Romance Studies, Liberation, Madame Proust by Evelyne Bloch-Dano, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention Manning Marable, Modern Language Association, Modernism/Modernity, Napoleon Bonaparte, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Humanities Center, North Carolina State University, Oleg Cassini, PEN, Stanford Humanities Cneter, study abroad, Susan Sontag, The Collaborator: The Trial and Execution of Robert Brasillach by Alice Kaplan, The Difficulty of Being a Dog by Roger Grenier, The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan, The Interpreter by Alice Kaplan, The Nation, Une Langue by Akira Mizubayashi, University of California Berkeley, University of Chicago Press, Yale French Studies, Yale University

Share it

(French) Alice Kaplan, author and professor of French at Yale University, was born in 1954 in Minneapolis and was educated at the University of California at Berkeley and Yale, where she received her Ph.D. in French literature in 1981. Her teaching career has taken her from North Carolina State to Columbia University, and then to Duke University, where she held the Lehrman Chair in Romance Studies. In 2009 Kaplan joined the faculty at Yale, where she holds the John M. Musser chair in French Literature.

(French) Alice Kaplan, author and professor of French at Yale University, was born in 1954 in Minneapolis and was educated at the University of California at Berkeley and Yale, where she received her Ph.D. in French literature in 1981. Her teaching career has taken her from North Carolina State to Columbia University, and then to Duke University, where she held the Lehrman Chair in Romance Studies. In 2009 Kaplan joined the faculty at Yale, where she holds the John M. Musser chair in French Literature.

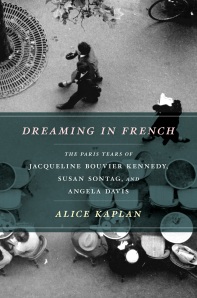

“Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis,” was published in April, 2012 by the University of Chicago Press and is forthcoming next fall from the Editions Gallimard in Paris.

A cultural historian of 20th century France with an expertise in the period of the German Occupation and Liberation, Kaplan is the author of the award-winning The Collaborator: The Trial and Execution of Robert Brasillach (Los Angeles Times Book Prize, 2001) and The Interpreter (Henry Adams Prize, 2006). She is probably best known for her French Lessons: A Memoir (1986), the story of her life-long love affair with the French language. Her new book, Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, returns to the abiding passion of French Lessons, tracing the transformative effects of a year in France on three American icons.

Kaplan is also a translator of fiction and non-fiction from French to English. Her translations include Roger Grenier’s Another November (1998) and The Difficulty of Being a Dog (2000) and Evelyne Bloch-Dano’s Madame Proust (2007).

Alice’s critical essays have appeared in Modernism/Modernity, The Nation, Yale French Studies, and in the French newspapers and magazines Libération, Le Point, L’Histoire, and Critique—where her article on Manning Marable’s Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention will appear this June 2012. She is the recipient of numerous grants and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Guggenheim Foundation, the Stanford Humanities Center and the National Humanities Center. In 2010 she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She serves on the usage panel of the American Heritage Dictionary and on the boards of Yale French Studies and La Revue Critique. She is a member of PEN, the Modern Language Association, and the American Association of Literary Translators. She lives in Guilford, Connecticut and in Paris.

INTERVIEW

Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis

AWP: What made you want to write this book?

AK: For several decades now, I’ve watched my women students prepare for their study abroad in Paris, then I’ve seen them come home, transformed. I’ve watched them gain not just in their sense of style but in their confidence, their eye on the world. I wanted to study this process of transformation by entering into the world of three important American women who studied in France—to see if I could understand how their year in France changed them, and how they changed our country because of it.

AWP: Why is now the right time to publish your book, Dreaming in French? Did you feel a need to share a particular time and place for students living abroad in the style of today?

AK: There’s a sense in which study abroad the old fashioned way— linguistic immersion, home stays, insertion in the French university —is an endangered experience. Many great universities are creating their own campuses in places like Singapore and Abu Dhabi. Others are offering programs in France where all the academic work is done in English. I wanted to remember a golden age of study abroad when we felt we had so much to learn from another country—a time when Americans were taking, rather than giving, the lessons. And when students made a vow to speak no other language than French—even with one another.

AWP: Why these 3 women—such different women—why did you decide to write about them together?

AK: These iconic figures in post war American society loved France—but for such different reasons. Bouvier’s France was esthetic, Sontag’s bohemian, and Davis’s political. These differences allowed me to convey three distinct educational and personal experiences, to offer readers different points of entry into French history and culture.

AWP: What’s the most surprising thing you learned about each of them?

AK: I was surprised by Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy’s literary talent, her gift for imagery in the short stories, letters, and prefaces she wrote. With Susan Sontag, it was her vulnerability behind the fierce intellectual front, and also the determined way she went about learning French, devising a language method of her own, that took me by surprise. In the case of Angela Davis, I had no idea when I began my research that she became such an important figure for the French. I learned that when she was in prison, awaiting trial, the same writers she had studied as an undergraduate in Paris came to her defense.

AWP: Tell us about the research for this book. What were the challenges, and how did you uncover these stories?

AK: I began by contacting the alumnae association at Smith College. They sent my letter of inquiry to each surviving student from the 1949-1950 Smith program in Paris. Many women wrote to me about their life-changing experiences, about their intellectual lives in Paris, their travels, their memories of daily life. What was especially fun was looking at the study abroad experience from both sides of the ocean: in France, interviewing the host families; in the U.S., talking to the students who studied abroad with Angela Davis and Jacqueline Bouvier; contacting Susan Sontag’s crowd of Paris friends from 1957-1958. I had great experiences in libraries and archives: I found Jacqueline Bouvier’s thank you letter to de Gaulle in the French National Archives; at Stanford, thousands of letters written to Angela Davis in prison; at UCLA, Susan Sontag’s diaries and correspondence. My research took me from Paris all the way to the west coast!

AWP: What did you like best about each woman?

AK: I was astonished by Jacqueline Bouvier’s lack of vanity, and touched by the deep happiness she achieved at the end of her life. With Sontag, I was charmed by the word lists she made as a young woman in France and by her reminder to herself in her Paris diary that she needed to read the Napoleonic code! With Angela Davis I admired her commitment, her ability to theorize and grow from tragic experience; her love of teaching.

AWP: What is it about France and women?

AK: That’s the million dollar question. Today, as I understand it, 75% of all French majors are women. There are the historical arguments: France linked to luxury goods, to the art of seduction, supposedly a woman’s art. But for the women I’m studying, it’s important to remember that they traveled to France before the great second wave of feminism. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was published in 1963, just as Angela Davis was leaving for the Hamilton Program. All three women lived in a socially repressive era without a women’s movement as ballast. According to the social mores of 1950s and 1960s, you were supposed to be engaged by your senior year—or else! Each of the women in my book found in France, in their different ways, a place where they could wander and explore, at a remove from their families and home expectations.

AWP: Napoleon Bonaparte, (1769-1821), a reactionary pragmatist regarding women, said in a letter written in 1795: “A woman, in order to know what is due her and what her power is, must live in Paris for six months.” Does this claim resonate with the lives of the women in your book? In what way does Napoleon’s statement hold true with your experience living in Paris? How is Napoleon’s statement understood by women of today?

AK: I so enjoyed discovering this quotation on A Woman’s Paris® mission. It might have been an epigraph for Dreaming in French—I only wish he had said a whole year!

The quotation comes from a letter Napoleon sent to his brother, Joseph, in 1795—during the last phase of the French revolution, after the Terror.

I couldn’t resist looking up the original:

“Une femme a besoin de six mois de Paris pour connaître ce qui lui est dû et quel est son empire.’

Imagine the young Corsican in Paris. He’s only 26 years old, identifying with these glittering women who’ve ascended to the capital, in the great French tradition of the ambitious provincial. He says women must come to Paris to “know their empire”—connaître leur empire. For Napoleon must already be dreaming of his own empire, through these women….

(Jacqueline Bouvier was descended from a cabinet maker named Michel Bouvier, who fought in Napoleon’s army and emigrated to Philadelphia during the White Terror, where he established himself by making furniture for Joseph Bonaparte, also in exile. So there is a nice connection between this letter and Jackie Bouvier’s French roots.)

LIVING ABROAD

AWP: How do you fit in with the three women in your book? Describe your own “Paris Years.”

AK: I describe my 1973-1974 junior year abroad in Bordeaux in French Lessons. Dreaming in French was a fun book to write because it allowed me to imagine what it would have been like to go to Paris instead. Now, Paris is where I spend my summers—so many summers that every street has a memory, even layers of memories. I’ll never forget the day I was walking down the Boulevard Saint-Germain and saw Susan Sontag in the Café de Flore, writing in her notebook. I hope there will always be hundreds of cafés in Paris where writers will go to make sense of the world.

AWP: In addition to being students of French history and culture, literature and politics; what French cultural nuances, attitudes, ideas, or habits were adopted by Bouvier, Sontag and Davis? In which areas have you embraced a similar aesthetic?

AK: A French aesthetic can be as simple as making a cross through your 7’s, or as all encompassing as Jacqueline Kennedy’s wardrobe: she understood in 1960, as her designer Oleg Cassini put it, that “clothes tell a story.” Her characteristic A-line dresses were inspired by Givenchy—the same designer who dressed Audrey Hepburn in the movie Sabrina, Billy Wilder’s study abroad fairy tale. For Susan Sontag, Paris was a place where you could be an intellectual without being a professor. She took that dream of an intellectual life outside the university back to New York. For Angela Davis, an early childhood fantasy about being from Martinique reverberated throughout her life—in her sensitivity to racial issues in France, her understanding of decolonization and black identity.

There isn’t one French esthetic, but there is an esthetic imperative in France—and that’s something I feel every time I walk down a Paris street.

AWP: In your book, Dreaming in French, you suggest that each of the three women were predisposed, each in their own way, toward France: through fantasy, family or a cultural context at that time. They each already held a piece of their French narrative, even before traveling. Was this the same for you, and if so, how?

AK: In fifth grade French class we had to choose a French name for our tests and papers, the name by which we wanted to be called on. I chose Jacqueline, after Jacqueline Kennedy (and I wasn’t alone in those years…). So doing research about the real Jacqueline Kennedy’s French education was a way of coming full circle, of deconstructing my childhood fantasy. France for me was Madeline the school girl, walking in the two straight lines; it was de Gaulle, taller than any world leader in JFK’s funeral cortège; it was the Seurat reproduction that hung in our living room and the coq au vin I made with my friend Priscilla, whose mom, my high school French teacher, had gone on the Smith Junior Year in Paris in the 1930s.

AWP: How well did Jackie Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis know French? And how did you figure that out?

AK: I spent hours in the audio visual room of the national library in Paris, listening to radio and television interviews with all three women. Jackie Kennedy had an elegant, classical French; she could utter a phrase like “je n’ai pas cet orgeuil’ that sounded straight out of a 17th century novel. And she knew how to cover up a mistake. Susan Sontag spoke French fearlessly and powerfully, without worrying too much about intonation. She was very much herself in her second language. Angela Davis, in her television interviews, has the most advanced syntax of the three; she’s comfortable using the subjunctive and debating political and social issues. Her host mother liked to say: “Angela a toujours le mot juste.”

AWP: In your book, Dreaming in French, you pose a striking question of Jacqueline’s school friends who were photographed standing in the shadow of a sign and paying homage to the Interdit, the forbidden way. You write, “…what have they decided is forbidden to them as American girls in Paris?” Where won’t they go? Does the concept of the forbidden define or shape the experiences of Jacqueline, Susan and Angela?

AK: Of the three, Susan Sontag was most drawn to the forbidden. She left a marriage and young child to spend a season in Paris with her lover, Harriet. In Paris, she wasn’t afraid of her homosexuality. The other women were breaking other barriers: Jacqueline Bouvier felt she had permission, in France, to explore the life of the mind. In Birmingham, Alabama, Angela Davis and her sister pretended to be from Martinique so they could be served at the front of the shoe store. For an African American girl In Jim Crow Alabama, the most basic public space was forbidden, and France—both the imaginary France and the real place—was a way out.

AWP: How has the idea of study abroad changed since these three women went? Do the internet and other new technologies make a true study abroad experience obsolete?

AK: Facebook, cell phones, internet, keep students in constant contact with their American friends and families. In Jacqueline Bouvier’s era, you could go for months without speaking to your parents—and that independence, while it could be lonely as well as exhilarating, made them the women they became. But the new technologies have plenty to offer: they allow students to make new networks of French friends, to experiment with the French language and document their discoveries. With technology, it’s all about what you do with it—you can use it to go out into the world or to retreat.

AWP: What do you think today’s women and men living abroad as students bring to the French?

AK: American students have a wonderful creative notion of learning; they aren’t shy in the classroom, and they haven’t been taught to learn by rote. My French colleagues are challenged and delighted by their experience teaching Americans, and often transform their own classrooms as a result.

AWP: Several of our contributors have lived abroad as students in France and Francophone countries. Many AWP followers are preparing to study or live abroad. What would you say to them?

AK: My American students have the schedules of Prime Ministers; their days are packed with extracurricular activities, appointments, clubs, in addition to regular schoolwork. I would say to them: in France, let yourself slow down! Dare to be lost or bored. I’d advise them to study the tops of buildings on every Paris street, to go into a different café each week, and spend four hours there. I’d tell them to write and read and go to the movies in the afternoon as generations of Americans in Paris have done before them.

AWP: In your youth, what did you imagine your adult life would hold? What influenced this vision?

AK: The writer I translate, Roger Grenier, said somewhere that you spend the first part of your life wondering what you’ll do with it and the second part trying to understand what you’ve done. When I was a child my world was defined by lakes—Lake Harriet in the winter, Lake Minnetonka in the summer, and by the fantasy of swimming in them as long as I wanted, from one end to another. I never dreamed I’d have to leave those lakes forever. But I did, and I still have a sense of wonder about learning French, and where that language has taken me.

AWP: What is the last book you read?

AK: At the end of the academic semester, I always delight in the first book I get to read that has nothing to do with classes. This year, it was a memoir by Akira Mizubayashi called Une Langue venue d’ailleurs, about a Japanese student’s passion for French. And of course I read Bringing up bébé the minute it came out. I’m a fan.

AWP: How do you express your own style or fashion?

AK: For me, style means, above all, the shape and sound of a sentence and the particular pleasures of living between two languages. I’m not much different from other French professors when it comes to liking—or at least liking to analyze!—all kinds of French style, whether it’s through clothes or movies or food.

AWP: What was your most memorable meal to date?

AK: In French Lessons I write about my first soufflé on the Place Dauphine, when I was fifteen. But that’s not a memory anymore—it’s a story. I was invited to lunch just last week by French friends here in Connecticut, to watch the first round of the French elections. They prepared an indoor picnic: a winter salad of beets and endives, nuts and banana; slices of foie gras, and champagne to drink. There was affection all around the table, new friends, a sense of history and debate, and children learning. It was a moment I’ll remember for a long time.

AWP: What is in your refrigerator right now?

AK: What a personal question! I have a European-size refrigerator in my kitchen: it opens up the space, and it also means I shop every day for fresh food. Yesterday there was nothing in it because I’d been on a book tour for a week. But last night a friend came over with salmon and new potatoes, fresh spinach, and a mixed fruit pie from the orchard market. And today it’s nearly empty again!

SELECTED BOOKS BY ALICE KAPLAN:

French Lessons: A Memoir. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993. A coming of age story, told through a girl’s abiding passion for life in another language.

The Collaborator: The Trial and Execution of Robert Brasillach. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. The trial of a French journalist and novelist who sided with the Nazis ended in the only execution of a major French writer after WWII — following a six hour treason trial. A moral who-done-it about freedom of speech and the death penalty.

The Interpreter. New York: Free Press and paperback, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. Racial injustice in the American army liberating France, seen through the eyes of French writer Louis Guilloux, an interpreter for a U.S. Army Court Martial in Brittany.

Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012. Three iconic American women in the post-war era were transformed by their year of study in Paris, and went on to transform American life.

Translations:

Roger Grenier, Another November; Piano Music for Four Hands (both from the University of Nebraska Press)

The Difficulty of Being a Dog; and the book Photography’s Secrets (forthcoming) — from The University of Chicago Press. Evelyne Bloch-Dano, Madame Proust. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED BY ALICE KAPLAN:

Nathalie Sarraute’s Childhood is going to be reissued next year by the University of Chicago Press. It’s one of the most beautiful stories I know about learning French, written by France’s premier New Novelist, whose family emigrated from Russia in 1909, when she was seven.

Albert Camus collected his most significant writing about Algeria in a volume called Algerian Chronicles, which has never appeared in English. Harvard is finally bringing out the translation next year, with my preface and a translation by Arthur Goldhammer — a master translator. In the wake of the Arab spring and so much interest in North Africa, and with the 50th anniversary of Algerian independence this summer, Camus’ anguished vision of Algeria in the thick of the country’s war for independence makes for fascinating reading.

Evelyne Bloch-Dano, Vegetables. New in translation from The University of Chicago Press this spring, this charming book is a “biography” of vegetables, complete with folklore and recipes. Evelyne Bloch-Dano is France’s leading biographer. (My last translation was her biography of Proust’s mother, Madame Proust, also available from the University of Chicago Press.)

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the following people for helping to make this interview possible: Alice Kaplan, author and professor of French at Yale University; Levi Stahl, Promotions Director at The University of Chicago Press; Natalie Ehalt-Bove, Lead Teacher at Joyce Bilingual Preschool in Minneapolis and editorial advisor for A Woman’s Paris®; Merle Minda, Travel Over Easy; and Ann Phillips, University of Minnesota.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® blog, French Impressions: John Baxter’s “The Perfect Meal” and Finding the Foregone Flavors of France. In this delightful culinary travel memoir, John Baxter follows up his bestselling The Most Beautiful Walk in the World by taking readers on the hunt for some of the most delicious and bizarre endangered foods of France. (French)

French Impressions: Anne Fontaine’s white shirts and the color of happiness. Anne Fontaine, a Franco-Brazilian fashion designer, entrepreneur, businesswoman and philanthropist, known as the “queen of the white shirt,” brought new faces and unforeseen levels of diversity to the fashion industry. Thanks to her, the white shirt is now definitely a staple on women’s wardrobes as a key piece. Anne shares her rise in the industry and 2011 launch of The Anne Fontaine Foundation, which is committed to the reforestation of the Brazilian rain forest. (French)

Ballet Flats in Paris: And God made Repetto, by Barbara Redmond who shares what she got from a pair of flats purchased in a ballet store in Paris; a feline, natural style from the toes up, a simple pair of shoes that transformed her whole look. Including the vimeos “Pas de Deux Coda,” by Opening Ceremony and “Repetto,” by Repetto, Paris. (French)

French Lingerie: Mysterious and flirty, by Barbara Redmond who shares her experience searching for the perfect lingerie in Paris boutiques and her “fitting” with the shop keeper, Madame, in a curtained room stripped to bare at Sabbia Rosa. Including a French to English vocabulary lesson for buying lingerie and a directory of Barbara’s favorite lingerie shops in Paris. (French)

Vive La Femme: In defence of cross-cultural appreciation. Kristin Wood finds Francophiles around the world divided about Paul Rudnick’s piece entitled “Vive La France” in the New Yorker magazine. As is often the case with satire, there is a layer of truth to the matter that is rather unsettling. Included are comments from readers worldwide. (French)

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2012 Alice Kaplan. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com

3 comments

Barbara Redmond said:

May 18, 2013 at 12:10 pm

This is a very interesting interview. I was fascinated by this approach of the French culture through Alice Kaplan and her books. I am going to buy Dreaming in French right away. Thank you Barbara for your quality work in this website and with the choice of your guests.

Christine Loÿs

(Originally submitted by Christine 2012/05/05)

Barbara Redmond said:

May 18, 2013 at 12:09 pm

Dear Christine,

After you read Alice Kaplan’s book, Dreaming in French, please share your thoughts with our guests and us. You are a Frenchwoman, author and documentary filmmaker who travels easily between France and the U.S. for work and pleasure. We are eager to hear from you about the cross-cultural experiences that have shaped your life. Thank you for your kind comment.

Barbara

To our readers: For our French Impressions interview with Christine Loÿs visit: http://awomansparis.wordpress.com/2012/03/07/french-impressions-an-interview-with-christine-loys/

(Originally submitted by Christine 2012/05/05)

Barbara Redmond said:

May 18, 2013 at 12:08 pm

Reblogged this on PORTAFOLIO. BITACORA DE UN TRANSFUGA. 2000.2010.

Manon Kubler

(Originally submitted by Manon 2013/05/05)