French Impressions: Ronald C. Rosbottom’s “When Paris Went Dark” – Marking the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris (Part One)

28 Thursday Aug 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Cultures, Interviews

Tags

Albert Camus, City of Light 1940-944, Colette, Jean-Paul Sarte, Joseph J Ellis Ford Foundation Professor Emeritus Mount Holyoke College, Joseph J Ellis Founding Brothers American Sphinx and Revolutionary Summer, Josephine Baker, Liberation of Paris 1944, Pablo Picasso, Paris under German occupation 1940-1944, Ronald C Rosbottom Amherst College faculty, Ronald C Rosbottom Amherst Massachusetts, Ronald C Rosbottom Romance Languages Department Ohio State University, Ronald C Rosbottom University of Pennsylvania, Ronald C Rosbottom Winifred Arms Professor in the Arts and Humanities professor of French and European Studies Amherst College, Scott Turow Identical, Simone de Beauvoir, Third Reich Paris occupation, When Paris Went Dark Ronald C Rosbottom Little Brown and Company

Share it

Ronald C. Rosbottom was born in New Orleans and educated at Tulane University and Princeton University. He is the Winifred L. Arms Professor in the Arts and Humanities and a professor of French and European Studies at Amherst College, where he also served as dean of the faculty. He previously taught at the University of Pennsylvania and the Ohio State University, where he served as chair of the Department of Romance Languages. He lives in Amherst, Massachusetts, with his wife, Betty, a cookbook writer.

Ronald C. Rosbottom was born in New Orleans and educated at Tulane University and Princeton University. He is the Winifred L. Arms Professor in the Arts and Humanities and a professor of French and European Studies at Amherst College, where he also served as dean of the faculty. He previously taught at the University of Pennsylvania and the Ohio State University, where he served as chair of the Department of Romance Languages. He lives in Amherst, Massachusetts, with his wife, Betty, a cookbook writer.

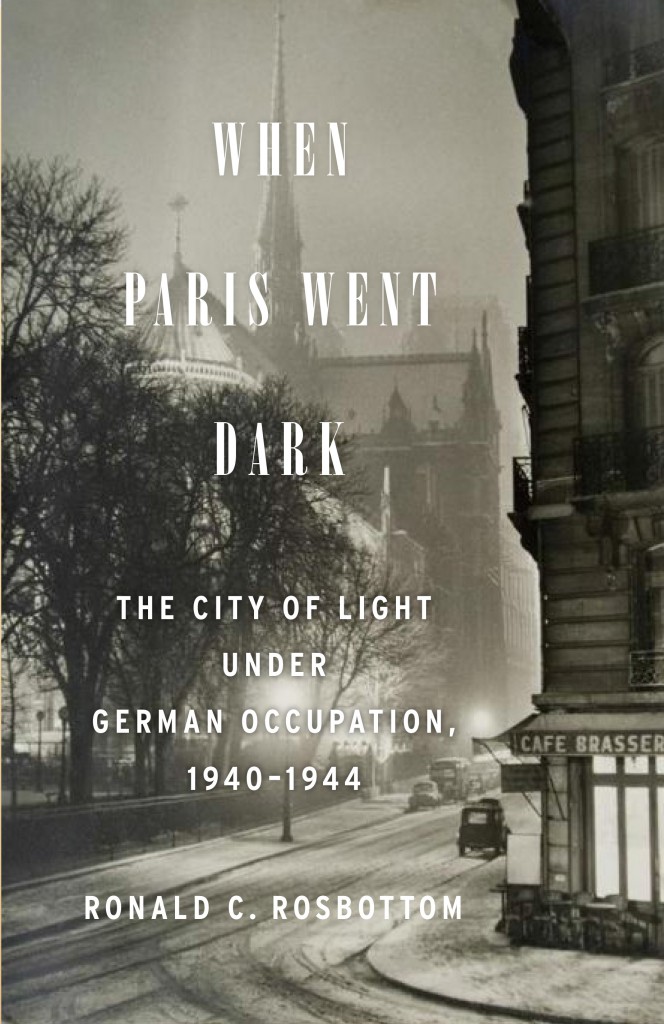

Marking the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris, Ronald C. Rosbottom’s When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944 (Little, Brown and Company) weaves a rich tapestry of stories to rediscover from the pavement up the texture of daily life in a city that looked the same but had lost much of its panache. (Purchase)

Marking the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris, Ronald C. Rosbottom’s When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944 (Little, Brown and Company) weaves a rich tapestry of stories to rediscover from the pavement up the texture of daily life in a city that looked the same but had lost much of its panache. (Purchase)

Using a vast range of sources—memoirs, diaries, personal letters, archives, interviews, unpublished personal histories, newspaper articles, histories, fiction, photographs, and film—Ronald Rosbottom forges an unforgettable history of both the important and minor challenges of day-to-day life under Nazi occupation, and of the myriad forms of resistance that took shape during that period. This expansive narrative will fascinate readers who are interested in the history and continuing legacy of World War II, Jewish history, the role of the arts in a repressive environment, and novels and films of that period, and, of course, lovers of France.

“Rosbottom explains the interaction of the French and their occupiers in a way that illuminates their separate miseries. He makes us see that we can never judge those who lived during the occupation just because we know the outcome. . . . The author attentively includes German and French letters and journals that explain the loneliness, desperation, and the very French way of getting by. . . . A profound historical portrait of Paris for anyone who loves the city.” —Kirkus (starred review)

“When Paris Went Dark recounts, through countless compelling stories, how Nazi occupation drained the light from Paris and how many of its residents resisted in ways large and small. This is a rich work of history, a brilliant recounting of how hope can still flourish in the rituals of daily life.” — Scott Turow, author of Identical

Excerpt from When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944 by Ronald C. Rosbottom. Copyright © 2014 by Ronald C. Rosbottom. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company (Part One)(Part Two).

INTERVIEW: When Paris Went Dark (Part One)(Part Two)

When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944

On June 14, 1940, German tanks entered a silent and deserted Paris. The City of Light was occupied by the Third Reich. Parisians were stunned, humiliated, and yet curious about the sudden appearance of thousands of German soldiers on their boulevards. The Germans too were curious: How do you treat a city that did not fire a shot in its own defense? Groups and individuals of all stripes—French and immigrant Jews, adolescents, communists, Gaullists, police officers, teachers, concierges, and landlords—endeavored to remind the German authorities that Parisians would never accept their presence. Cultural icons such as Josephine Baker, Picasso, Sartre, de Beauvoir, Colette, and Camus developed their own strategies to resist being overpowered by an invidious ideology.

AWP: You are the author of When Paris Went Dark. What inspired you to write this book?

RR: From my first visit to Paris as a college junior I wondered what it must have been like to be “occupied,” and how Parisians had adapted. Years later, I taught courses on the history of Paris, and the question kept coming up. How did Paris survive the massive destruction of World War II?

AWP: You entrench your work in a different part of Paris’ past, taking stock of city that did not fire a shot and mapping the transformation of different type of occupation. What challenges did you encounter, and how did you unfold the story you wanted to tell?

RR: The history of the Occupation is still a fraught one, with as many versions as there are first-rate historians. The unique arrangement between the Third Reich and the État Français, the conservative (“Vichy”) government, has continued to complicate memories of those four years. I had to do a lot of reading and-rereading to untangle the skein of memories, false and true, that have made it into France’s collective memory, and “official” history.

AWP: A book can only be so long. Is there a subject you would have liked to treat more fully?

RR: Yes, I think readers would have liked to read more about the role of the Catholic Church in the Occupation, both the institution itself and individual priests and nuns. And there are many tales there, but “a book can only be so long.”

AWP: Many well-known personalities remained in Paris during most of the Occupation. For instance, you mention Simone de Beauvoir and Picasso. Was that unusual?

RR: Not really. Let’s remember that artists, performers, and writers had to continue to deal with daily life just as did others less talented or prominent. Some felt that staying was a sign of confidence in the city and its inhabitants, a willingness to keep up morale. Others stayed to advance their careers, not distinguishing between German or French audiences. Still others stayed because they needed the vitality of the city as their muse, and, obviously, to hear the approval of an audience.

AWP: How do we understand the term collaboration in the grey-zone of life in France during World War II?

RR: This is perhaps the most ticklish question confronting those who write about this period. I try to use consistently “collaboration,” when referring to close interaction with Germans and their Vichy partners in order to enhance one’s business, career, or political agenda. I use “accommodation” to describe what almost everyone had to perform as they tried, daily, to interact with a powerful, omnipresent, and capricious occupying force. If I provided the German Army with the products of my industry, or if I arrested other Parisians for their political or religious beliefs, I was most likely a “collaborator.” If I served coffee politely to the same German officer who came to my café every morning, or said “pardon,” if I brushed past a German soldier, I was trying to “accommodate. However, the ranges of daily and regular interactions were so broad that these distinctions are only partly useful.

AWP: What were the social and political attitudes of the period?

RR: France was a very divided country politically. There were those who believed that secularist (read, anti-Catholic Church) and socially progressive factions were undermining the values of the more conservative, Catholic, pro-military sections of the population. Immigration from other European countries and North Africa was on the rise. Riots between these factions had broken out in Paris streets in the 1930s, and a Jew—a JEW!, Léon Blu–had been selected Prime Minister twice. By the time that the Germans arrived in Paris, there were those, but certainly nowhere near a majority, who chanted “Better Hitler than Blum!”

AWP: What part did Americans play in the eighteen months between the Occupation of Paris and the U.S.’s entry into World War II?

RR: Americans tried to stay out of the deeply divided loyalties of the French. They did not support de Gaulle, who had gone to London and declared himself leader of the Free French, thereby contradicting Philippe Pétain’s claim that he and the Vichy government were France. They attempted to work with Pétain and his “Vichy” government to maintain what they saw as a bastion against further German encroachment in Europe. Many Americans stayed in Paris up until the last moment, December 1941, when Hitler declared war on the U.S.

AWP: How descriptive were the French and foreign press, especially American, about daily life during the early Occupation.

RR: The Germans immediately took over the French press, and of course censored publications that came from the U. S. or the U.K. The French though heard much about the war from the BBC, which put both self-exiled Frenchmen and American journalists on their airwaves. From these sources, many learned of the increasing hardships imposed by the Occupation.

AWP: How is the story of the Occupation itself remembered and retold in French culture? What do they hide and what do they preserve?

RR: This too is a complicated question, for one of the most interesting aspects of French history since 1945 is how groups and persons have tried to control the collective memory of the Occupation. There were many different resistant groups, some small, some large, of several political persuasions; there were groups of veterans, police, railway men—all who demanded some credit for having participated in opposing the Germans. And then there was the strong desire on behalf of Charles de Gaulle to bring France together after what had been, after all, a low-burning civil war. The result was a muddled history, a “forbidden garden” whose gates many believed should be left closed. But beginning in the 1970s, more and more efforts, in the form of novels, then histories, to ask new questions and devalue bromides, tried to come to some sort of agreed-upon version of a complicated period. The process continues.

AWP: Your research is exemplary. How did you accumulate and obtain this information? Was it primarily in French? What were the challenges, and how did you uncover these stories?

RR: Most of my sources were in French, then in English, then German, and a smattering of other languages. Many of my sources were from books published right after the war, and since forgotten. Other sources include fiction, film, and newspapers of the period. I also did interviews with those who lived during the period or whose relatives had. I was always looking for hints that there was something under the “official” stories, the personal memories. But I had to learn to read very carefully and to listen even more carefully. More than anything, I wanted to be fair to all those concerned, even the Germans, so that the story I told would be believable.

AWP: How long has it taken for the “whole story” of the Occupation of Paris to become known?

RR: It still isn’t known; every few months, some aspect pops up, some long-forgotten memory, some found treasure, some trove of letters or a diary. There is still much to tell, and I am always surprised when I visit Paris to see yet a new shelf full of books on the Occupation, on the deportation of the Jews, and on the brave acts of those who endeavored to protect them.

AWP: When you started writing When Paris Went Dark, did you have a sense of what you wanted to do differently from other accounts of the occupation of Paris?

RR: Yes. I didn’t want to write a bureaucratic or military or even a social history of the period. I wanted to bring forth what I have called a “tactile” history, that is, one that would give some sense of how it felt to walk, work, raise a family, and love in a city whose built environment changed very little, but whose aura was starkly cracked. Almost every daily action demanded some sort of ethical decision, from the occupier and the occupied, about interaction with others. How does one discover these moments, isolate them, and then narrate them? That was my challenge.

AWP: What was the most surprising thing you learned?

RR: I had not known how meticulously the Germans had planned a possible occupation of Paris. During World War I, they had tried and almost succeeded twice to capture the capital, and it is obvious that they intended to be ready a third time. They had not only detailed maps, but the very plans of blocks, of apartment houses, where the rich, especially rich Jews, lived. They knew every road, every alleyway, every sewer location, and they even knew which public buildings and hotels had front and back entrances.

AWP: Why is the message of the Occupation of Paris significant, especially today?

RR: For me, and my students, it raises the difficult but unavoidable question; what would you have done?

An ancillary question concerns the moral costs of the occupation on the occupier.

Acknowledgements: Alyssa Noel, student of French and Italian, and Journalism at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities and English editor for A Woman’s Paris.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post French Impressions: Barbara Will on Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the intellectual life during wartime France. From 1941 to 1943, Jewish American writer and avant-garde icon Gertrude Stein translated for an American audience thirty-two speeches in which Marshal Philippe Pétain, head of state for the collaborationist Vichy government, outlined the Vichy policy barring Jews and other “foreign elements” from the public sphere while calling for France to reconcile with its Nazi occupiers. In her book, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, Barbara Will outlines the formative powers of this relationship, treating their interaction as a case study of intellectual life during wartime France.

French Impressions: Tilar J. Mazzeo’s “The Hotel on Place Vendôme” – 1940s sex, parties and political intirgue at the Ritz in Paris. This riveting account uncovers the remarkable experiences of those who lived in the hotel during the German occupation of Paris, revealing how what happened in the Ritz’s corridors, palatial suites, and basement kitchens shaped the fate of those who met there by chance or assignation, the future of France, and the course of history. Tilar J. Mazzeo, is author of the New York Times bestseller The Widow Clicquot, and The Secret of Chanel No. 5. (excerpt)

French Impressions: John Baxter on the First World War: A reflection on Paris’ history and transition during the war years. John Baxter, acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer, is the author of The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal, The Golden Moments of Paris, and his most recent book, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918. For four years, Paris lived under constant threat of destruction. And yet in its darkest hour, the City of Light blazed more brightly than ever. Including an excerpt from Paris at the End of the World (excerpt).

French Impressions: Dr. Alan T. Marty on the dark history of the City of Light. Alan T. Marty, MD, armed with an historically-informed exploratory spirit, has often encountered Paris’ endless capacity to evoke a mood, to surprise with similar absent/present paradoxes, as detailed in his A Walking Guide to Occupied Paris: The Germans and Their Collaborators, a book-in-progress. His work has been acknowledged in Paris dans le Collaboration by Cecile Desprairies, Hal Vaughan’s book Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War; and referenced in Ronald Rosbottom’s When Paris Went Dark, and in an upcoming book about Occupied Paris by Tilar Mazzeo.

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2014 Ronald C. Rosbottom. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com