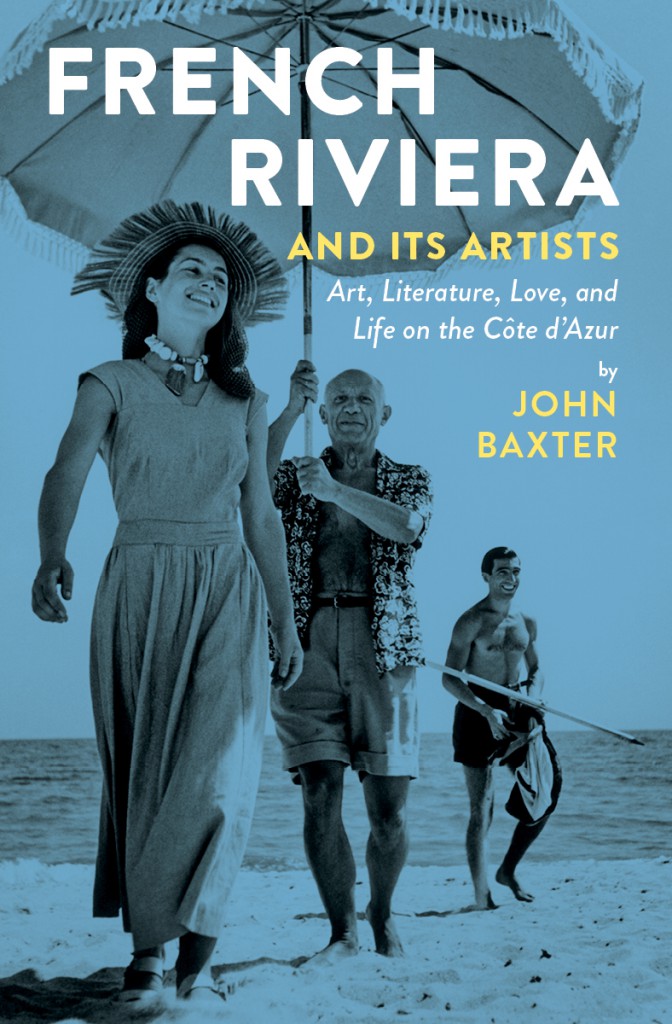

John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “THE WALLS SPEAK FOR ME”: Jean Cocteau and the Villa Santo-Sospir (excerpt)

09 Thursday Jul 2015

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Cultures, Travel

Tags

Academie Francaise, Art Literature Love Life Côte d'Azur France, Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, Coco Chanel Saint-Tropez, Colette, Côte d'Azur, Crusades and the Order of the Knights and Dames of the Holy Sepulcher of Jérusalem, Editions du Rocher publishers, Erik Satie, Etienne de Beaumont, F Scott Fitzgerald Tender is the Night, Francine Weisweiller, François Mauriac, François Truffaut's La Nuit Americain, French Riviera, French Riviera and Its Artists John Baxter, Greta Garbo, Henri Matisse, Jean Cocteau Parade ballet, Jean Marais, Jean Martinon Nicoise banker, Jean-Pierre Melville, John Richardson art historian, La Belle et la Bête Beauty and the Beast Jean Cocteau, Last Supper Jean Cocteau, Le Sang d'un Poète The Blood of the Poet Jean Cocteau, Le Train Bleu Jean Cocteau, Les Enfants Terribles Jean Cocteau, Marcel Proust, Marlene Dietrich, Max Jacob poet, Menton French Riviera, Milly-le-Roi Jean Cocteau, Misia Sert, Museyon publishing, Nijinsky La Spectre de la Rose, Notre Dame de Jérusalem Fréjus France, Orphée II yacht, Orphée Orpheus Jean Cocteau, Oscar Wilde, Paul Poiret, Picasso, Raymond Radiguet novelist, Roger Pelissier ceramicist, Sergei Diaghilev Parade Ballet Russe, South of France, St Jean-Cap-Ferrat France, The Walls Speak for Me Jean Cocteau and the Villa Santo-Sospir John Baxter, Villa Santo-Sospir Côte d'Azur, Villefranche-sur-Mer French Riviera

Share it

Excerpt from French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur – “THE WALLS SPEAK FOR ME”: Jean Cocteau and the Villa Santo-Sospir, by John Baxter. © John Baxter. Reproduced by permission of Museyon. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur – “THE WALLS SPEAK FOR ME”: Jean Cocteau and the Villa Santo-Sospir, by John Baxter. © John Baxter. Reproduced by permission of Museyon. All rights reserved.

Get swept up in the glitz and glamour of the French Riviera as author and filmmaker John Baxter takes readers on a whirlwind tour through the star-studded cultural history of the Côte d’Azur that’s sure to delight travelers, Francophiles, and culture lovers alike.

Baxter introduces the iconic figures indelibly linked to the South of France—artist Henri Matisse, who lived in Nice for much of his life; F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose Riviera hosts inspired his controversial book Tender is the Night; Coco Chanel, who made the Saint-Tropez tan an international fashion statement; and many more of the legendary artists, writers, actors, and politicians who frequented the world’s most luxurious resorts during the golden age.

For jesters and armchair travelers alike, French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur is sure to become an instant classic and will make even the most dedicated home-bodies yearn for the land of cafés and literary greats. (July, 2015, Museyon) (Purchase)

Praise for French Riviera and Its Artists

“These luminaries celebrated life and created art amid paradise and this book is the ultimate guide to the Riviera’s golden age.” —Christine Gray, luxurytravelmagazine.com

“As with all Museyon guidebooks, the volume is richly illustrated: The back matter alone features an art gallery of the French Riviera and its artists, but paintings are interspersed throughout the book.” —June Sawyers, Chicago Tribune

“This richly illustrated and beautifully formatted work” —Library Journal

Subscribers, French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur by John Baxter bestselling author of The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, and We’ll Always Have Paris. Free book giveaway to two subscribers ends July 15, 2015.

Free Subscription: Join our thousands of followers to receive your copy of our Readers’ Choice: 253 Books About France, including books about Architecture, Interiors and Gardens; Arts; Biography; Children; Culture; Fashion; Food and Wine; Memoir; Mystery; Novel; Science; Travel; and War, along with email notifications of new posts on the website.

Once subscribed, you will be eligible to win—no matter where you live worldwide—no matter how long you’ve been a subscriber. We never sell or share member information.

Excerpt: John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “PABLO PICASSO”: In a Season of Calm Weather… (excerpt) published with permission on A Woman’s Paris®.

Excerpt: John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “MANY FÊTES”: The Hôtel du Cap and Tender Is the Night published with permission on A Woman’s Paris®.

Interview: French Impressions: Author John Baxter and Editor Janice Battiste – conversations on the evolution of the book, “French Riviera and Its Artists” on A Woman’s Paris®.

French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur (excerpt)

“THE WALLS SPEAK FOR ME”:

Jean Cocteau and the Villa Santo-Sospir

by John Baxter

Graphic artist, playwright, poet, novelist, film director—Jean Cocteau was too multi-talented for his own good. In a period characterized by commitment and specialization, his contemporaries scorned his failure to join some movement or embrace a creed. Cocteau felt himself to be above petty categorizations. He preferred to echo Oscar Wilde, who, on being asked by U.S. Customs if he had anything to declare, is said to have replied, “Only my genius.”

Nothing about Cocteau was conventional, least of all his childhood. His father committed suicide when he was nine. He was raised by his maternal grandparents and an often absent mother, whom he believed to be an actress, perennially on tour—until, at twenty, he recognized her in photographs taken in a womens’ prison. A kleptomaniac, she had been serving sentences for theft.

As a child, Cocteau contracted what he called “the red and gold sickness”—a love of theater. It proved incurable. Everything he touched took on the quality of a performance, even his service during World War I. With crossdressing socialite and dilettante Etienne de Beaumont, he joined a private ambulance unit put together by socialite Misia Sert, friend of Marcel Proust and Erik Satie, and lover of Coco Chanel. To transport the wounded, Sert co-opted the delivery vans of couturiers Jean Patou and Paul Poiret, which were standing idle since the army drafted the design and tailoring staff to make uniforms.

After leaving Sert’s comic-opera enterprise—“I realized I was enjoying myself too much,” he confessed—Cocteau responded to a challenge from Sergei Diaghilev to “Astonish me” by conceiving Parade (1917), a ballet set in a circus. He coaxed Satie into writing the music and persuaded Picasso to design it by turning up at his home dressed as a clown. He also wrote Le Train Bleu (1924) for Diaghilev, with costumes by Coco Chanel and décor again by Picasso. Turning to cinema, he directed the controversial short film Le Sang d’un Poète (The Blood of Poet, 1932) with money from Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles. Once he began making feature films, La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast, 1946) and Orphée (Orpheus, 1950), both starring his lover Jean Marais, became instant classics.

Attracted to athletic young working men, both as partners and models, Cocteau had been part of the group that waited in the wings of the Ballets Russe to sponge down a sweaty Nijinsky as he staggered off stage after a strenuous performance in such ballets as La Spectre de la Rose (1911). Later he rescued gay writer and habitual criminal Jean Genet from a potential life sentence by hiring one of France’s best defense counsels to fight his case.

But while he appeared to know everyone, Cocteau remained essentially a loner. In François Truffaut’s La Nuit Americain (Day for Night, 1973), the star, Jean-Pierre Aumont, dies in the midst of shooting. When the producer reflects that, spending his whole life on location, the actor was “at home nowhere,” the director, played by Truffaut, disagrees. “He was at home everywhere. He died hurrying back to us, his friends.”

The same could be said of Cocteau, who was seldom found at his apartment in Paris’s Palais Royale, near that of his friend Colette. As winter came, he migrated south to the Riviera. An inveterate house guest, he was welcome in homes all along the Côte d’Azur and left his mark in most of them. Sometimes it was only a sketch scribbled in a guest book, but given even a little encouragement he would break out his brushes and dash off a mural.

In 1950, money ran out midway through the filming of his novel Les Enfants Terribles. To raise more, director Jean-Pierre Melville suggested they find a wealthy patron with artistic pretensions on whom Cocteau could exercise his charm. The perfect choice, Francine Weisweiller, proved to be right under their noses, since they were already filming in her house, which was next door to the Paris mansion of Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles on Place des États-Unis.

The Brazilian-born wife of an American oil millionaire, Weisweiller was spoiled, beautiful, rich, well-connected, and flattered by the attention of the multi-talented Cocteau. In taking him under her wing, she also inflicted a subtle revenge on her husband for his long-standing affair with actress Simone Simon. Francine persuaded her spouse to invest in Les Enfants Terribles (1950), and invited the unit to continue filming in Villa Santo-Sospir, their summer home in St. Jean-Cap-Ferrat. When shooting ended, Cocteau stayed on in the villa, ostensibly to rest. It was to be his Riviera home for more than ten years.

Summer at the villa became one long house party. Picasso regularly visited, along with Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. Though Weisweiller’s Bentley was always waiting in the garage and her yacht Orphée II was moored nearby, she, Cocteau, his adopted son Édouard Dermit and their friends seldom left the house. Why bother, when she so generously indulged his tastes for opium and attractive young men? According to art historian John Richardson, the group was “bound together by mutual admiration—a sort of collective narcissism.”

Francine took over management of Cocteau’s career. Editions du Rocher, the press she co-owned with her brother, became his publisher. She was also instrumental in getting him elected as one of the forty “immortals” of the Académie Française, the ultimate honor for French intellectuals. Some members of this staid group found her lobbying offensive. When it admitted Cocteau in 1955, novelist François Mauriac wrote dryly “He did not stumble into our assembly dazed. He has had his eye fixed on the door for quite some time, waiting for it to open a crack so that he could slip in.”

Cocteau repaid his debt to Weisweiller with art, creating tapestries, ceramics and mosaics for her homes. When she suggested the fireplace at Santo-Sospir needed brightening up, he surrounded it with a mural showing figures from Greek mythology. His two-dimensional style, something like cartooning—he called it “tattooing”—lent itself to wall painting, while his sexual inclination towards young sailors with Grecian profiles provided plenty of fuel for his imagination.

Above the fireplace, he painted a full-face black, gold and yellow image of the sun god Apollo, flanked by two giant Priests of the Sun, modelled by fishermen from nearby Villefranche-sur-Mer, the little fishing town he had first discovered in 1924, at the time of Le Train Bleu. Inspired, he went on to decorate the entire house, including the furniture. “He said that he found the silence of the walls terrible,” recalled Weisweiller’s daughter Carole. “He learned from Matisse that once you paint one wall, the other three look bare.” The work took six months. Later he remarked, “At Santo-Sospir, I’m most myself, and the walls speak for me.”

Francine found him more commissions. In 1957, he decorated the dockside chapel of Saint Peter in Villefranche. Local fishermen again posed for the scenes from the life of Peter, Christ’s “fisher of men.” Picasso was polite about the result, but as Carole Weisweiller acknowledged, “The only work that interested Picasso was his own.”

The same year, Francine negotiated a deal with the town of Menton for Cocteau to decorate the salle des mariages in the town hall. Since he found the room “rather unsympathetic,” he decided, he explained, “to adapt the style of the turn of the century on the Riviera, with its villas, mostly now gone, interspersed with bunches of iris, seaweed and heads of waving hair.” Before he was done, he had not only painted the walls and ceiling but redesigned the furniture, the lamps, the curtains, and added some incongruous touches of his own, including a few panther-skin rugs. In his spare time, he also created a small museum in the Bastion, a seventeenth-century fort built into the town’s sea wall. Local pebbles made up a mosaic floor and the stone walls were hung with tapestries in medieval style.

No matter how great the charm of a house guest, most eventually wear out their welcome. Cocteau’s relationship with Weisweiller soured in 1963, when she took a lover of whom he didn’t approve. Cocteau moved to Villefranche. Despite efforts by Jean Marais to repair their friendship, they were never reconciled.

Before his death in 1963, Cocteau accepted one more mural project, but didn’t live to finish it. Financed by Nicoise banker Jean Martinon, the chapel of Notre Dame de Jérusalem in the hills above Fréjus was to have been the centerpiece of an artists’ colony. Cocteau planned the octagonal building with architect Jean Triquenot and executed some of the decoration, notably a Last Supper at which the apostles are portraits of Coco Chanel; Jean Marais; poet Max Jacob; novelist Raymond Radiguet, Cocteau’s one-time lover; Francine and Carole Weisweiller; and Cocteau himself. After his death, Édouard Dermit and ceramicist Roger Pelissier completed the decoration—poorly, in the general opinion. As neither Martinon, a freemason, nor Cocteau was conventionally Catholic, the chapel employs often obscure imagery, some of it related to the Crusades and the Order of the Knights and Dames of the Holy Sepulchre of Jérusalem.

After her break with Cocteau, Francine Weisweiller, in poor health and with much of her fortune gone, became a recluse, barricaded like a sleeping beauty behind the umbrella pines and banks of crimson hibiscus that shielded the villa from the outside world. She died there in 2004. Four years later, it became a national monument. Cocteau is buried in the Paris satellite town of Milly-le-Roi but his spirit speaks to us from the walls of Santo-Sospir.

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is the author of the memoirs: The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, and Five Nights in Paris. A native of Australia, he currently lives with his wife and daughter in Paris—in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is the author of the memoirs: The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, and Five Nights in Paris. A native of Australia, he currently lives with his wife and daughter in Paris—in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

Since moving to France, John has published biographies of Federico Fellini, Luis Bunuel, Steven Spielberg, Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, Josef von Sternberg, Robert De Niro, and the author J.G. Ballard. He has also written five autobiographies, including A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. His most recent books are Chronicles of Old Paris and The Paris Men’s Salon, a selection from his uncollected prose pieces. John’s translations of Morphine, by Jean-Louis Dubut de la Forest and Fumée d’Opium, by Claude Farrère, have also been published by HarperCollins, the latter as My Lady Opium.

John has co-directed the annual Paris Writers Workshop and is a frequent lecturer and public speaker at universities and writers workshops. His hobbies are cooking and book collecting (he has a major collection of modern first editions). When not writing, he can be found prowling the bouquinistes along the Seine or cruising the internet in search of new acquisitions.

In 1974, John was invited to become a visiting professor of film at Hollins College in Virginia, U.S.A. While in the United States, he collaborated with Thomas Atkins on The Fire Came By: The Great Siberian Explosion of 1908, a highly successful book of scientific speculation, and wrote a study of director King Vidor, as well as completing two novels, The Hermes Fall and Bidding. (Facebook) (Website)

Photo: Rudy Gelenter

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “PABLO PICASSO”: In a Season of Calm Weather… (excerpt). In 1959, fantasy writer Ray Bradbury published the short story In a Season of Calm Weather. It describes an enthusiast for Pablo Picasso who visits the Riviera in hopes of meeting him. Walking on the beach one evening, he does indeed run into the artist and watches in wonder as Picasso, using nothing but a small stick, idly scratches a riotus frieze of nymphs and satyrs in the wet sand. But his delight has a downside…

John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “MANY FÊTES”: The Hôtel du Cap and Tender Is the Night (excerpt). “On the pleasant shore of the French Riviera, about half way between Marseille and the Italian border, stands a large, proud, rose-colored hotel. Deferential palms cool its flushed façade, and before it stretches a short dazzling beach. Lately it has become a summer resort of notable and fashionable people,” begins Scott Fitzgerald in his book Tender Is the Night, the finest of all Riviera novels, with this description of the Côte d’Azur’s most exclusive hotel.

French Impressions: Author John Baxter and Editor Janice Battiste – conversations on the evolution of the book, “French Riviera and Its Artists”. “Writers interviewed by the media or at festivals often describe the crucial moment they decided to write a book,” writes John Baxter. “In my experience, such moments seldom exist.” John never set out to write a book about the French Riviera and its artists. The idea caome from a New York publisher, Akira Chiba, who owns a small company called Museyon. Akira handed editing of the book to a trusted collaborator, the free-lance editor Janice Battiste. Janice and John had worked with great congeniality on The Golden Moments of Paris, so it was a pleasure for them to set out again. The extracts from John and Janice’s emails synopsize the process by which they jointly brought The French Riviera and Its Artists to a successful conclusion.

John Baxter’s “Five Nights in Paris” – a dazzling sensory tour of Paris’s greatest neighborhoods (excerpt). Acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer, John Baxter’s Five Nights in Paris: After Dark in the City of Light is enriched by ancedotes from Baxter’s own life in France and written with the alluring, authoritative voice only he can provide. He is author of the memoirs: The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal, The Golden Moments of Paris, and Paris at the End of the World.

John Baxter’s “Paris at the End of the World” – Patriotism transforming fashion (excerpt). Preeminent writer on Paris, John Baxter brilliantly brings to life one of the most dramatic and fascinating periods in the city’s history. Uncovering a thrilling chapter in Paris’ history, John Baxter’s revelatory new book, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, shows how this extraordinary period was essential in forging the spirit of the city we love today.

Travel Diaries: “To Catch a Thief” on the Côte d’Azur by Barbara Redmond who brings us a story of travellers who had come to the French Riviera, like her, to indulge in the sea and glitter by night. Reading until the professeur de natation was folding the last beach umbrella, then to dress for the evening.

Travel Diaries: To the South of France with Love. Sara Horsley invites us into her world to share six weeks in Arles, France, during a study abroad program. There, she learned about the French culture and their respect and admiration of artistic expression.

Readers’ Choice: 253 Good Books About France. Your quest is to dig below the surface, peek behind the façade, where lurks a story, rumor, recipe or fossil. We have an eagerness to explore fresh ideas, to forge powerful relationships and build a community. Readers, we invite you to draw close this narrative, woven on A Woman’s Paris, a narrative that has come to life, to discover secrets of the past and take part in shaping the future. Become a part of our conversation. We celebrate the art and ideas of people from every place and every heritage.

Mireille Guiliano’s “Meet Paris Oyster” on the Parisians’ love for them (excerpt) – part one. Mireille Guiliano, a former chief executive at LVMH (Veuve Clicquot), is “the high priestess of French lady wisdom” (USA Today) and “ambassador of France and its art of living” (Le Figaro). She is the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller French Women Don’t Get Fat: The Secret of Eating for Pleasure, as well as French Women Don’t Get Facelifts. With her characteristic wit, wisdom, and storytelling flair, Mireille will soon have you wanting to eat oysters at least every week. Including a recipe for Oyster Vichyssoise.

Text copyright ©2015 John Baxter. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com

1 comments

Jacqueline Bucar said:

July 9, 2015 at 4:29 am

A fascinating story and while I was reading it with mouth wide open, I couldn’t help wondering how on earth Baxter researched this chapter. Diaries I would guess but then where did he find all the other myriad details of his life and his works? Incredible research! I’ve always been impressed by John Baxter as a writer but the depth of this research makes him even more impressive. Thanks for posting this. I enjoyed it thoroughly